The media created two messages out of the movie premier of “Virginia City” —that authentic western culture lay in the decaying mining town southeast of Reno and that the mainstream view of “western” had missed the reality of the place. It now remained for bohemians to come to Virginia City—though some had already arrived in the 30s—to market it both as an artifact and finally, as a living tradition of entertainment for all that was wild in the old mining culture. That mining culture had long been tied to the roots of ragtime in the fandango house, to ragtime and then to the honky tonk jazz revival of the ‘20s. From the late ‘40s to the late 1980s, Virginia City would become a unique center for ongoing saloon honky tonk—attempting to keep alive the liberal, bohemian world of mining culture—though, in the 1990s, it would largely give way to the sanitized “western” theme.

Much has been written about how Virginia City, in 1965, helped inspire San Francisco’s psychedelic music scene. Generally missed has been the connection between this singular event and Reno’s jazz hysteria during the 20s as well as the effort to then clean up or civilize that music with a “western” theme during the late 30s.

Jazz thrived in cabarets with their variety shows and in ballrooms with broader social dancing. In small towns, due to Prohibition, there were few if any cabarets. The local grange halls and movie theaters served as ballrooms. In Virginia City, the Virginia Theater hosted jazz dances from 1921 into 1924—most of them played by Tony and his Melody Men. A 1921 ad for the first jazz dance in Virginia City was placed in the Carson City paper to attract jazz dance fans to Virginia City. Earlier in the year, the city had held a huge celebration attempting to attract tourists to the town.

In May 1924, Tony played jazz music for dancing at Piper’s Opera House in Virginia City. The Opera House is said to have been ”packed to the doors.” It was falling apart and closed for 15 years after the dance.

The Modern Bohemians

These qualifications to use of “honky tonk” as some kind of timeless western reality help in looking at the honky tonk revival that took place in Virginia City, beginning during the late 1940s.

About 1936, as “Go Western” began to become very popular in Reno and Tony was beginning to bring in large swing bands during the swing era, sleepy Virginia City—the old mining town—was beginning to be recognized as a western relic. Ragtime music—often called “honky tonk”—would arrive ten years later and by 1960 Virginia had become a mecca of early jazz.

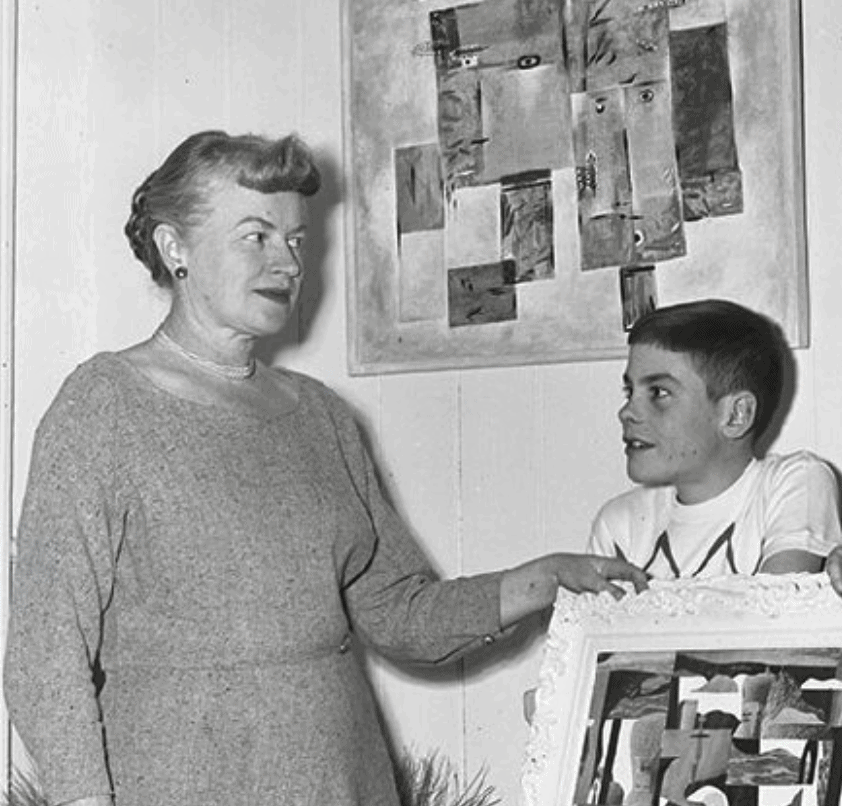

By the mid to late 30s, the divorce/drinking trade in Virginia City began to attract literati and artists. Virginia City’s bohemian arts crowd at the Union centered on the Sierra Nevada Brewery—the home of the modernist painter Zoray Andrus who arrived during 1936. Her son, Peter Kraemer, grew up in the city’s saloons midst this cosmopolitan western bohemian crowd comprised of old time miners, somewhat reformed crooks and international visitors. Andrus is today recognized as prominent in the post-war bohemian arts scene of northern Nevada. Virginia City artists like Zoray were ultimately better known in California than in Reno due to the lack of galleries/venues for art-work in the region.[1] She became a primary conduit for the ongoing connection between Virginia City and Bay Area—by-passing the tendency for Reno art to be primarily focused on the University and what Kraemer calls the “Latimer crowd” of light-weight realists.

An eastern folklorist, Duncan Emrich, visited and spent portions of three successive years in Virginia City beginning in 1937. Emrich began the process of memorializing Comstock characters like the madam, Julia Bullette, in sketches. At the time he was an instructor in English literature at Columbia University.[2] In 1940 he published a small book of Comstock poems titled, “Who Shot Maggie in The Freckle”. In 1939, Emrich had divorced his wife in Reno.[3] In 1940 he married Marion Wright of Virginia City.[4] The small book’s poems seem composed by Emrich himself, during the late ‘30s in the Bucket Of Blood saloon—opened by Versal McBride in 1931 upon the end of Prohibition[5]. The title poem’s sexual double entendre illustrates the embrace of “honky tonk” or low art in Virginia City even as, in Reno, the nation’s general tendency toward a higher/cleaner lyric was taking hold. Emrich’s little book signaled the bohemian salon culture in Virginia City and a return to mining culture’s cosmopolitan focus.

Emrich’s book of poems reflected his personal immersion in the ghosts of the old mining center as they came alive, fueled by the divorce industry and nights in the bar. His poem book represents a temporary slip. Like others associated with the elite bohemian revival of Virginia City during the ‘40s and ‘50s, during his career Emrich disdained any modern effort to revive culture as a living tradition. As a folklorist he later wrote that disliked the watered down, modern “pseudo-folk” trend.[6] Emrich’s little book presages the more life-like or active revival of Virginia City that would occur during the 1960s, with the stage for that set during the 1950s. Its title illustrates the beginning to a trend that would continue in Virginia City’s honky tonk period—barely disguised double entendre with over sexuality just below the surface. Where “jazz hysteria” as focused in the 1920s across the nation and on Reno in the 1930s tended to worry about broad social decline as women were lured into sin, the honky tonk bohemian community in Virginia City embraced sexuality with a vaudeville humor.

In 1947, the modern poet Irene Bruce (1903-1987) and her piano player husband, Harry Bruce, arrived in Silver City, just below Virginia City.[7] Harry had played piano on the radio as a child in Oklahoma. In 1947, he recorded with Freddy Nagel’s Band. During the early 50s, Bruce played some with Freddy Nagel, in Susanville.[8] Nagel was panned by the critics for adding too many gimmicks to his shows—firemen hoses, fake moustaches and noses. Nagel once said, “nobody liked us but the customers”. In other words, in front of a live audience, Nagel played honky tonk. This does not come through in his recordings. During 1947, with Bruce at the piano, Nagel recorded four songs for Vitacoustic. Let’s look at Harry and listen to one. Note that all the rough edges have been removed—all the fire hoses, fakes moustaches and noses. When we note the local recital scene that Andrus probably fostered in the late 30s, it seems the big change to culture in Virginia City came with Irene Bruce. Contrasting a verse from an early Reno poem with one from Virginia City we can see the changes in Irene’s poetry as well as the increasingly abstract nature of Andrus’ paintings, we see that, at least through the 1950s, ragtime in Virginia City was allied to the bohemian and later beatnik effort to find an alternative to modern slickness.

While living in Reno, Irene had published a poem in ’42.[9] She self-published “Crag And Sand”, her first poetry book, in Reno during 1945. She published a second book, “Night Cry”, in Virginia City during 1950. In that book, her poem, “Virginia City” contrasts the visiting socialites with the fading old Comstockers. She noticed the distance between the booming tourist scene and the reality of the past. She included the poem in, “Sage In Bloom”, a book published by the Nevada Federation of Women’s Clubs, 1950—a collection of mostly non-vernacular yet, nonetheless, traditionally structured poetry. In contrast, her piece heralded a shift away from rhyme and structure.

In short, the Bruces’ arrival appears to signal the beginning of a growing honky-tonk music scene in Virginia City—one that struggled through the 50s and took off during the 50s. He is said to have been able to start a classical piece and shift it into ragtime. At some point he played at the Union Brewery with Jack Curran on the banjo, Elmer Von Scheibel (“Spoons”) on the spoons and Bad Water Bill on the gut bucket.[10]

He had played piano on the radio as a child in Oklahoma and later for David Brinkley’s Journal[11] when the NBC television show covered Marriage Mills of Nevada during June of ’63. Apparently, at that point honky tonk piano seemed perfect to portray Nevada. By 1958 he was playing six nights at week at Virginia City’s Western Bar And Cafe.[12] He was still playing in 1965.[13]

During the 1950s, the term “honky tonk” was popularly applied to tinny music, often in a western saloon where, many people believed, in the Gay Nineties only a mechanical keyboard instruments or a single piano player could be afforded. In this sense, western “honky-tonk”—the name deriving from the thin sound of its music—descended from the California and western fandango house where men could both drink and dance. Country western song-writers picked it up from this usage.

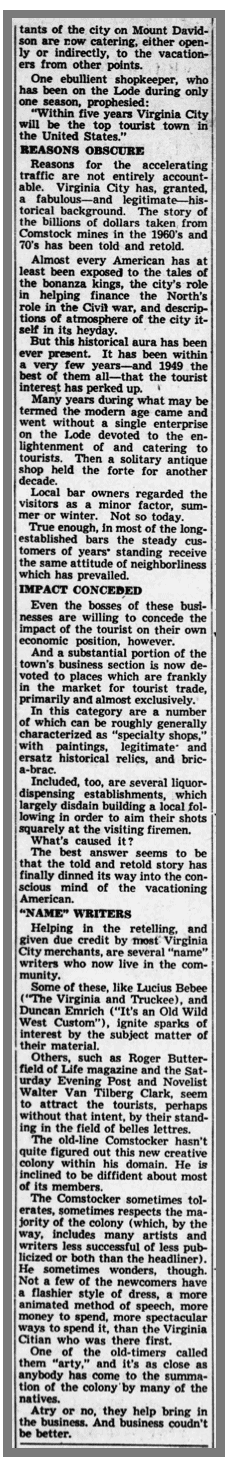

During 1948, well known “dude”, historical and socialite, Lucius Beebe purchased a private railroad car to be housed in Carson City as he explored Wells Fargo history and continued his interest in old railroads.[14] Virginia City society would now soon see two “salons”—the more famous and wealthy surrounding Beebe, the more artistic surrounding Zoray.[15] That being said, the two were friends.[16]

By 1947, Zoray was seen as the “guiding spirit” of artists exhibiting in Virginia City.[17] In contrast, arriving in the wake of the movie, “Virginia City,” historian and bon-vivant Lucius Beebe created a different kind of Bohemian interest. He bought the Territorial Enterprise newspaper and used it  to promote preservation of the town’s artifacts.

to promote preservation of the town’s artifacts.

Among other things, the city contained a host of old pianos as well as some two dozen mechanical musical instruments, all dating from around the turn of the 20th century—a time when, apparently, hiring musicians happened rarely despite the need for music in the saloons. In Virginia City, there is little evidence for anyone playing ragtime on these instruments prior to 1947. Hollywood movies about cowboys, the cold war and the centennial of the California gold rush in 1949 all made the survival of an authentic “western” town important to Lucius Beebe and his cultured friends.

Beebe tried to save The Virginia And Truckee railroad. He bought and brought back to life The Territorial Enterprise newspaper. Its ads for entertainment came from Reno.[18] However, the movie “Virginia City” and then Beebe’s promotion made Virginia City a focus for what people in Nevada thought of for the genuine “old west”, even though they couldn’t agree on that definition and the mining element of the town increasingly got lost.

Where history remembers Beebe whose vignette driven picture of Virginia City echoed the Harold’s Club vignette created by Myrtle Myles, it was Andrus and her artist friends who began to see Virginia City as a living historic location. The term “beatnik” was no in vogue, yet they fit that description.

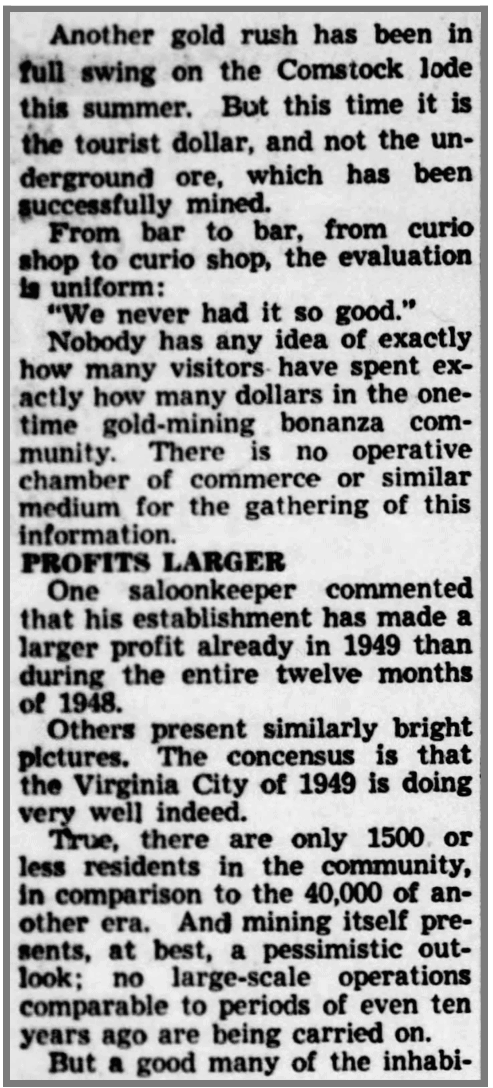

By fall of 1949, Reno noticed the rise of Virginia City tourism and the role of the newcomers—the bohemian crowd. The Reno Gazette Journal described the old Comstocker’s view of these artsy people. The article foreshadowed the role of art in a re-vitalization of Virginia City that would not fully launch for ten more years.

“Ragtime” Bob Darch

Where Beebe saw Virginia City as a collection of artifacts and Andrus saw it as a hub of writers and painters, Bob Darch (31 March 31, 1920 – October 20, 2002)[19] saw it as a place for revival of the 1890s honky tonk saloon and music. He wanted to bring western saloons alive. Coming during the mid-1950s, this followed over a decade during which “western” music on guitar by singers in cowboy hats had framed western music as everything from swinging jazz to maudlin country songs.

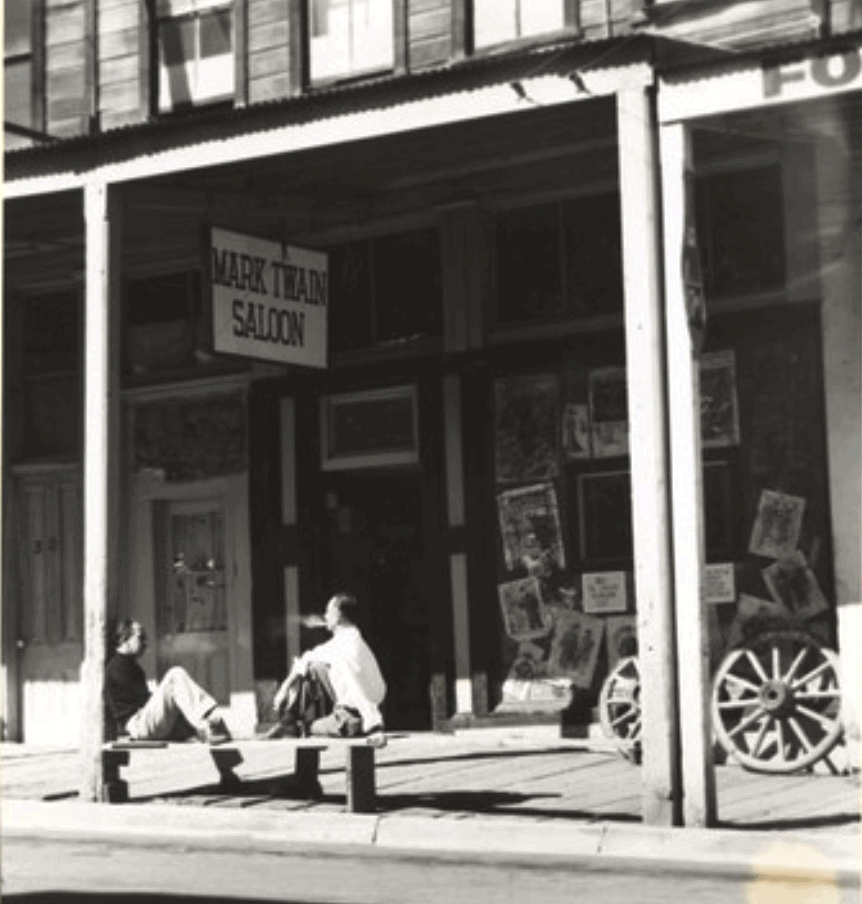

An April of 1953 article describing the coming season in Virginia City described only one live musical act, Nine Hines singing at The Comstock House.[20] Around 1953, The Mark Twain Saloon, advertised for a “genuine” ragtime piano player. The saloon housed an arts gallery including works by Zoray Andrus who was present at its opening in 1946.[21] 63 year old Hattie Jessup (1892-1983) answered the ad. [22] In 1906, Jessup had begun performing publicly as a movie-theater pianist in Allentown, Pennsylvania.[23] A Reno painter, her husband had turned her into a housewife for 17 years but had recently died.[24] She has been described as a “fat lady arrayed in silver who looked like she had performed in the circus.”[25] She always wore gloves to protect her nails.

Jessup played ragtime piano in Virginia City for three years.[26] At some point, she seems to have moved to the Skydeck Saloon.[27] In 1954, the western group, Curley Duran and his Virginia City Ramblers, played at the saloon as well however this does not appear to have caught on. [28] Duran and other “western” musicians played mostly along Highway 40 in Reno. Jessup played piano in the window of the Mark Twain Saloon three years—a sort of musical artifact among the relics advertised at the old saloons.

Lucius Beebe may have been behind a 1954 song by Cliff Ferre and Jack Brooks, “The Virginia  And Truckee Line”—a song Ferre probably sang in his Reno show.[29] A television and film actor, singer and song

And Truckee Line”—a song Ferre probably sang in his Reno show.[29] A television and film actor, singer and song  composer, Ferre appeared during ’53 and ’54 as the singing MC at the Hotel Golden in Reno.[30] The show featured Fifi D’Orsay’s Parisian Follies. Ferre wrote many pop/ragtime songs, some with double entendre in the lyrics. The song is obscure—I found no copies of the record.[31] Lawrence Welk recorded it on Coral records.

composer, Ferre appeared during ’53 and ’54 as the singing MC at the Hotel Golden in Reno.[30] The show featured Fifi D’Orsay’s Parisian Follies. Ferre wrote many pop/ragtime songs, some with double entendre in the lyrics. The song is obscure—I found no copies of the record.[31] Lawrence Welk recorded it on Coral records.

During 1956, her satin blouse and her belt with 65 silver dollars, Hattie Jessup moved to The Red Dog Saloon in Juneau, Alaska. She became famous there as. “Juneau Hattie”—performing into the 1960s, recording a 45rpm record there in 1964 and still sometimes performing in Alaska in 1970.[32] By 1972 the original Juneau Red Dog Saloon had closed. Jessup had returned to Reno and was playing there.[33] She suffered a stroke in 1979 and moved to Santa Cruz.[34] She died in 1983 at age 91.

The saloon name “Red Dog” seems to stem from a turn of the century honky tonk saloon, around 1877, in Tombstone, Arizona.[35]

The previous year, 1955, Ragtime Bob Darch had played at the Red Dog in Juneau. He’d been a paratrooper on D Day in Europe and, after the war, was stationed in Alaska.[36] In 1958, he gave an interview in Wyoming where he stated that he had been noticed in Alaska by the novelist Edna Ferber who wrote an article about Alaska for Fortune Magazine and that he then spent 21 months playing in Las Vegas. This was not true. The article was not by Ferber, it didn’t mention Darch by name and the Nevada city in which he performed for 21 months lay in northern Nevada—Virginia City.[37] He played at the Delta saloon.[38] The Fortune article noted and dismissed the cosmopolitan atmosphere of the Alaskan frontier mining town—a rustic frontier vibe that equally applied to Virginia City at the time. Darch played on a “tack piano”—a piano in which brass tacks mounted on a leather strap rest against the strings under the hammers.

Juneau’s Red Dog Saloon, most colorful drinking spot in the territory, offers all the appurtenances of a Gay Nineties evening: snuff for the ladies, singing bartenders, saw-saw-dust covered floors, free lunch, a twelve-selection nickelodeon, and a non-stop professor at the piano.

The Red Dog Saloon, delightful though it be, is about as representative of contemporary life in Alaska as the Gay Nineties Club is of Manhattan. The kid that handles the music box there happens to be an ex-major of the Army Engineers (now making $30 plus per day), and the tinny tones of his otherwise normal piano come from a brass and leather strap cunningly placed in front of the string. The best dancer on the floor is probably the young Indian who met his blonde partner several years ago when segregated high schools were abolished in Juneau. The talk around the tables has a currency and scope remarkable in any stateside city of any times Juneau’s size (6,000), for adversity has honed Alaska wits and put as much of a premium on the double-edged word as the double bitted ax.[39]

Darch seems to have seen Virginia City as having potential for a similar zany, frontier, honky tonk scene—a place for revisiting the western Gay Nineties. Presumably, he’d had this vision in Alaska and then felt Nevada a more likely or profitable place to achieve it. Another influence on Darch may have been the traditional jazz or “dixieland” scene in San Francisco—centered on Lu Waters, Bob Scobey and Turk Murphy, among others. Their audience included many of college age. They tended to play loudly while the crowd danced and drank.[40] Darch’s promise that his music would help people “relive those tumultuous days and nights” equated authenticity to a low, honky tonk milieu. And, this seems to be what Darch meant when he insisted that he played “folk music.” In the notes to the sheet music of “The Opera House Rag”, Darch wrote that his works would be tied to drinking and the vibrant saloon, not “insipid” modern music, and should be played as written. He saw ragtime as a form of folk music at a time when “folk” music meant a rebellious, beatnik revolt against vapid pop music.[41] More broadly, it seems that, while swing and bebop had taken jazz into high realms of intellectual respectability, Darch, the dixieland musicians in the 1950s San Francisco bands and many of their young audience members felt in line with a street level, beatnik experience.

In 1956, Darch relocated to Virginia City, apparently swapping venues with Hattie—he coming to Nevada from Alaska and Jessup going to Alaska from Nevada.[42] The vibe Darch sought is perhaps best conveyed by a photo from later, in Florida. It may seem dated today. In context, it is an embrace of alcohol, the gay 90s and ragtime in the context of a revived honky tonk—bringing the modern age into the vitality presumed to exist in the past. In Virginia City, Bob Darch found little local support. During the 1950s, in the old mining center, promotion of a live music seems to have been a novel idea. Everyone seems to have subscribed to the idea of the living museum. Beebe’s “Territorial Enterprise” did little to advertise local music, perhaps because the Reno casinos payed good money to advertise their shows. The Delta advertised a “music hall” early in the decade. Jessup played at The Mark Twain Saloon.

In 1956, to Virginia City,[43] from The Red Dog Saloon in Juneau, Darch brought his favorite songs, such as “Nobody Else Can Love Me Like My Old Tomato Can”—first recorded in 1923 by Bill Murray, later a big hit for Tiny Tim.[44] The song lyric is a good example of the double entendre that defined “honky tonk” both in the 1920s and then for Darch and the bohemian crowd in Virginia City during the 1950s.

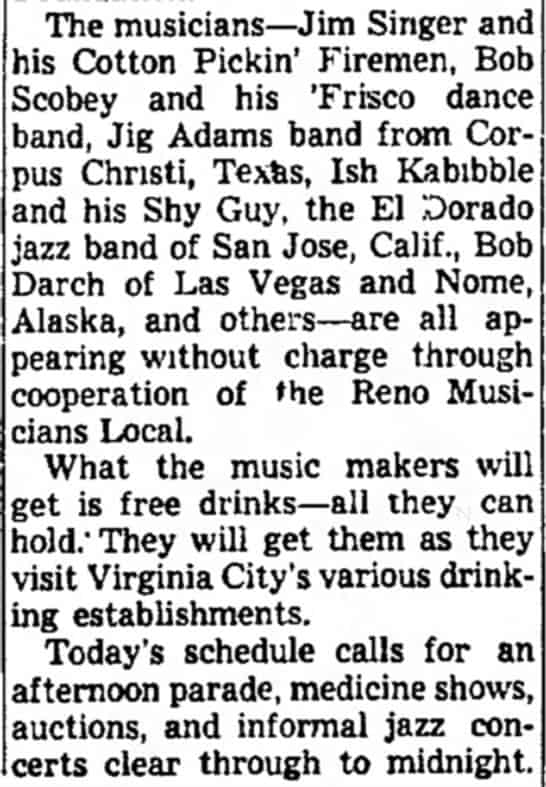

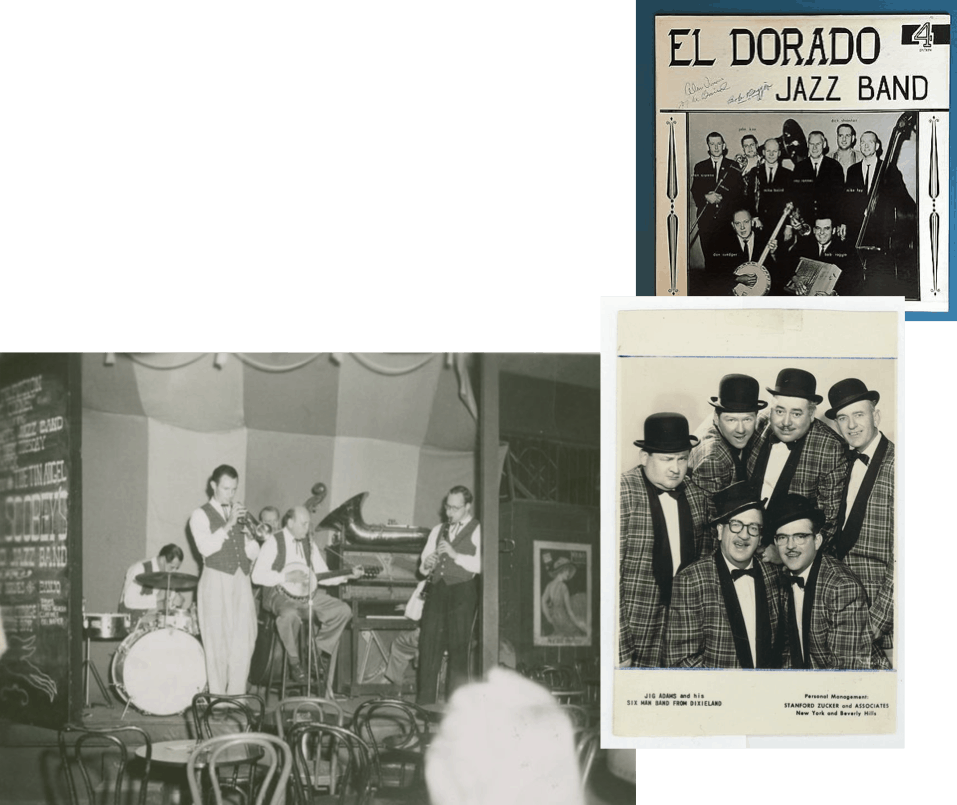

During 1956 and ’57, Darch held a local Ragtime And Jazztime Festival.[45] The 1957 article describes the event.[46] In “57, he brought in Bob Scobey and the Yerba Buena Jazz Band, Ish Kabibble and the Shy Guys, Jig Adams And His Six Man Band and the Eldorado Jazz Band and Jim Singer and His Cotton Pickin’ FIremen, a dynamic lineup. They played, parading into town. He maid them in drinks, though there may have been some money from the Reno Musicians Union. Ish Kabibble (Merwyn Bougle) son, Pete, attended and has written:

By the time the Dixieland Jazz Festival took place in Virginia City in the late Fifties, Dad was at the top of his game with his band, Ish Kabibble and the Shy Guys. In the opinion of his side men Dad was one of the best horn players they had ever performed alongside. The Dixieland Festival in Virginia City was a lively toe-tapping event for musicians and spectators alike. Some spectators danced down the street alongside their favorite bands soaking up the beat. The bands held forth in the saloons that lined the main street into the late evening hours. [47]

Darch had a vision of ragtime music memorializing the town. He seems to have been planning an album of Virginia City rags. Corresponding with early ragtime legend and composer Joseph Lamb, he composed “The Opera House Rag.” The back cover to this sheet music listed ten local ragtime titles —“Other Descriptive Ragtime”. He published the composition in Virginia City during 1960, probably at the very end of his time there. By ’58 he was playing in Wyoming, Missouri and Florida and even more widely in ’59. He did not play the tune on his 1960 LP, “Burl Ives Presents Bob Darch”.

Darch seems to have found little support among Virginia City’s bar owners for his festival idea. While Andrus headed a salon of artists, through the 1950s the economic idea of Virginia remained defined by Lucious Beebe and his vision of the City as an artifact.

Letters indicate that, during summer of 1959, Darch was corresponding with the aged, famous ragtime composer Eubie Blake (1887-1983), getting his help to compose “The Virginia City Rag.”[48] The music to “The Virginia City Rag” and these other Virginia City titles mentioned in his notes have never surfaced.

During 1962 in Dawson, Canada at the Monte Carlo Dance Hall, purchased in 1960 by Burl Ives,[49] using a ragtime orchestra Darch recorded “The Opera House Rag” as part of an album called “Gold Rush Daze”.[50] It was a concept album—a recording of a performance in which he and others enacted a night in an 1890s mining saloon. In all likelihood, this was close to what he intended  for the many rags he had intended to write in Virginia City, Nevada.

for the many rags he had intended to write in Virginia City, Nevada.

Darch seems rot have returned to raw far north with his concept of Gay Nineties in a mining town. Probably reflecting what he had intended for Virginia City, this was a concept album with actors. It undoubtably took a great deal of work to create a live show that that could be recorded in one take and that show perhaps ran for a time in Dawson. The scene was set in the Alaska gold rush with folksy frontier narrative and a variety of songs and instrumentals recorded uninterrupted in front of a live audience. Darch included “The Opera House Rag,” written in Virginia City and, in the narrative, assigned it to Dawson’s Palace Opera House.

THE WESTERN SALOON CATCHES ON

In 1958, Dave Bourne began playing western saloon piano at Knott’s Berry Farm in California. The 1950s honky tonk western piano aesthetic lead Bourne to de-tune his pianos. He focused on a Stephen Foster based repertoire in search of 19th century authenticity—consistent with the 1860s repertoire that, it appears, characterized miners’ tastes during the late 19th century.[51]

In 1958, the Reno paper carried an article about Harry Bruce playing in Virginia City. This marked a beginning to the City showing interest in marketing music.

During the mid-1950s, with marketing dominated by Beebe, Virginia City generally remained caught up in a vision of itself as artifacts. This jibes with the kind of historical folk-story that mirrored structured or traditional verse and song from the time of the State’s founding. Darch’s ideas proved too far-reaching for Virginia City at the time. For his ragtime/traditional jazz festivals, Darch is said to have gone to businesses in Virginia City yet failed to get support for his festivals.[52] According to one account, the musicians showed up, drank the town dry and left Darch with the bill. In late 1959, disillusioned with prospects in Nevada, Darch took his idea and his piano to Club 76 in Toronto where he launched the Canadian traditional jazz revival.[53] He brought Joseph Lamb to Canada for a performance.[54] In Toronto, he later brought the aged Eubie Blake back to the public eye.

Darch left behind an idea. Two or three long time piano players now lived in  town and played on C Street. Known for his pointy beard and top hat, born about 1905, Art Rafael played at the Silver Queen until 1970 or so.[55] And Harry Bruce was featured in a Reno article during 1958, evidence the saloon owners were ready to advertise honky tonk in its various forms. Probably around 1958, when it was owned by Carol and Jerry Eaton, Morrie Arnold recorded a 78rpm record at the Capitol Saloon of two piano rags. [56] This would be the first recording in Virginia designed for sale from the stage. And he had a postcard. In the photo on the card, his satin red shirt provides an interesting, local slant on the image of the old miner. Traditionally, tourist town miners often wear red flannel shirts in imitation of the standard gold rush garb. Here, Morrie wears a miner hat yet has upscaled to an entertainer’s mining shirt. Based on a 19th century establishment of that title, the Capitol Saloon was short-lived in its modern form. Yet, here, a year before the well-known 1959 blossoming of Virginia City tourist efforts a musician not only has a postcard but records a honky tonk 78 record to sell from the stage.

town and played on C Street. Known for his pointy beard and top hat, born about 1905, Art Rafael played at the Silver Queen until 1970 or so.[55] And Harry Bruce was featured in a Reno article during 1958, evidence the saloon owners were ready to advertise honky tonk in its various forms. Probably around 1958, when it was owned by Carol and Jerry Eaton, Morrie Arnold recorded a 78rpm record at the Capitol Saloon of two piano rags. [56] This would be the first recording in Virginia designed for sale from the stage. And he had a postcard. In the photo on the card, his satin red shirt provides an interesting, local slant on the image of the old miner. Traditionally, tourist town miners often wear red flannel shirts in imitation of the standard gold rush garb. Here, Morrie wears a miner hat yet has upscaled to an entertainer’s mining shirt. Based on a 19th century establishment of that title, the Capitol Saloon was short-lived in its modern form. Yet, here, a year before the well-known 1959 blossoming of Virginia City tourist efforts a musician not only has a postcard but records a honky tonk 78 record to sell from the stage.

One of the songs on the 78 is “Ace In The Hole”, famously sung in the 1950s by Clancy Hayes whom Darch had brought to town with Bob Scobey’s band in 1957. Darch left Virginia City and then proved instrumental in reviving ragtime in Scott Joplin’s hometown of Sedalia Missouri.[57] One wonders if he would have done any of this if Virginia City had embraced his vision of 1890s honky tonk saloons. In the wake of Darch, it would be Harry Bruce who still dominated the ragtime piano/honky tonk scene in Virginia City during 1958.[58] Darch had tried to project a wild west fantasy into Virginia City and only a few years later this same vision would more than thrive in the town. But Darch came and went before that happened.

As later described by Darch’s friend, pianist Peter Lundberg:

Bob Darch told you never to forget that ragtime came from places with sawdust on the floor, a bar with a brass rail and a spittoon. The ragtime of the saloons was not concert ragtime. It was music that helped get the evening going and that evolved along with the merriment. There was also the salon ragtime, the rags of the Big Three. Music for your drawing room enjoyment, with beautiful melodies and an appealing cover. [59]

Bonanza

By 1959, in Virginia City, the shift to an active tourist town—more than just artifacts—was underway. Darch seems to have been too bold in his big plans for the town. However, the Comstock shared with Darch as belief in the sawdust approach. Though, today, the imagery of the television show “Bonanza” may seem consistent with a range of commercial western movies and television shows, at the onset, the show invoked images that had arisen in Nevada during the 1920s.

“Bonanza” imagined the Cartwright’s spread “The Ponderosa”, near Lake Tahoe and with frequent reference to Virginia City.[60] The series seems to have reflected Hollywood’s ongoing marketing of the gunfighter cowboy—the hero in the white hat who, in the shadow of the cold war, brought justice to the lawless West. Lorne Green recorded “Ol’ Tin Cup”. The song’s nostalgic and somewhat ponderous lyric juxtaposes the modern cowboy and relics from the days of mining. With its story of the desert, the song draws on Nevada’s 1920s sage-and-pine poetry.

Ol’ Tin Cup,

copyright 1960 Max Rich[61]

I was riding my horse in the desert

Tired and weary of mind

Not knowing what I was searching for

And not caring what I might find

When suddenly, there in the desert

My old buck stumbled and to my surprise

He uncovered a world of greens right before my eyes

There was an ‘ol tin cup

A battered old coffee pot

A saddle, a pick, and a spade

All that remained of the hopes of a miner

And the wonderful plans he once made

A rusty old rim from the wheel of a wagon

The strings of a guitar he once played

Giving mute testimony from an old ‘49er

And the wonderful plans he once made

A hand full of nuggets lay gleaming in the sun

Right next to the gun he used to hold

You see he had learned from a friend

That the end of his rainbow was just a bag of fool’s gold

There was an ‘ol tin cup

A battered old coffee pot

A good book from which he had prayed

Telling the story of an old ‘49er

And the wonderful plans he once made

There was a favorite picture of a girl there too

In a pretty gingham dress, rested near a letter

That had told how a stranger had come along and had taken her away

And her love for him had grown cold

Beside that ol’ tin cup

A battered old coffee pot

I knelt with his good book and prayed

To the Lord, please take care of the old ‘49er

And the wonderful plans he once made

Apparently because Bob Darch had proselytized his sawdust vision of music in saloons, by 1959, Virginia City was primed to embrace a more active tourist scene. “Bonanza” lit a fire under this effort. Around 1959, looking at the success of the Calaveras County Frog Jump, the owners of the Bucket of Blood, the McBrides, invented the Virginia City Camel Race—having found a precedent in the City’s colorful past. This began a growing list of weekend—the Outhouse Races, Street Vibrations, St. Paddy’s Parade etc., defining Virginia City as a playground for thousands of weekend tourists from California. Virginia City would full embrace itself as a tourist mecca, yet, as it had with Darch, repeatedly now push back against any bohemian tendency towards anything the local owners perceived as complete chaos.

As late as 1960, the Reno paper still characterized Virginia City according to Beebe’s curio-laden vision—attractive for its “relic filled saloons”[62]—the image Beebe had promoted through the 50s. However, a more tourist focus proved more than the old-guard of Bohemians could tolerate. About 1959, Lucious Beebe ceased to be actively involved in the City. At the same time, Zoray Andrus sold the Sierra Nevada Brewery building to a Christian/yoga cult leader who later burned it to the ground for the insurance money. She thought this would be better than selling the old place to local brothel owner, Joe Conforte.

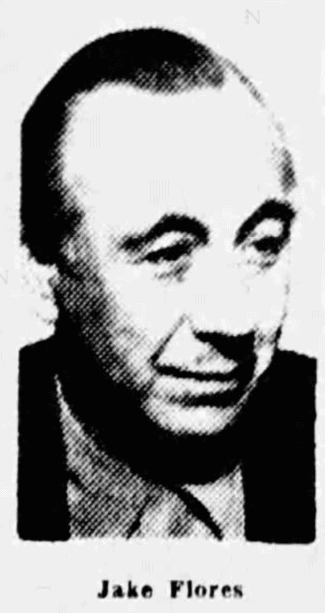

In 1959, The Mark Twain Saloon began a Sunday Dixieland Jazz Concert, hosted by Jack “Tailgate” Flores. Beginning his career in 1917, Flores had played during the early 20s with Paul Whiteman. With Wingy Manone, Flores recorded The Tailgate Ramble in 1944—and this seems to have been his signature piece. He played a style called “tailgate trombone”.[63] The term originated with bands playing in wagons when the trombone player would need room for his slide and would sit on the tailgate. As described by Flores, tailgate trombone came to mean the instrument doing bass effects, answering the cornet.[64] [65] [66] The Jack Flores concerts marked the first effort by a venue in Virginia City to advertise the old style jazz consistently. They seem to have only lasted a couple months. The next two decades of honky tonk or trad jazz in Virginia City would come as the trad jazz “revival” of Dixieland waned in the major or urban venues. It would enjoy venues in out of the way places like Virginia City into the early 1980s. Somehow, the aesthetic nature of the town and honky tonk melded in the public’s imagination. To some degree, Bob Darch was responsible for this. While Darch had left, he told others about Virginia City, including Swedish ragtime pianist Peter Lundberg, shown here visiting in 1963 and playing a piano at the Bucket Of Blood saloon. The association between Virginia City and honky tonk was spreading.[67]

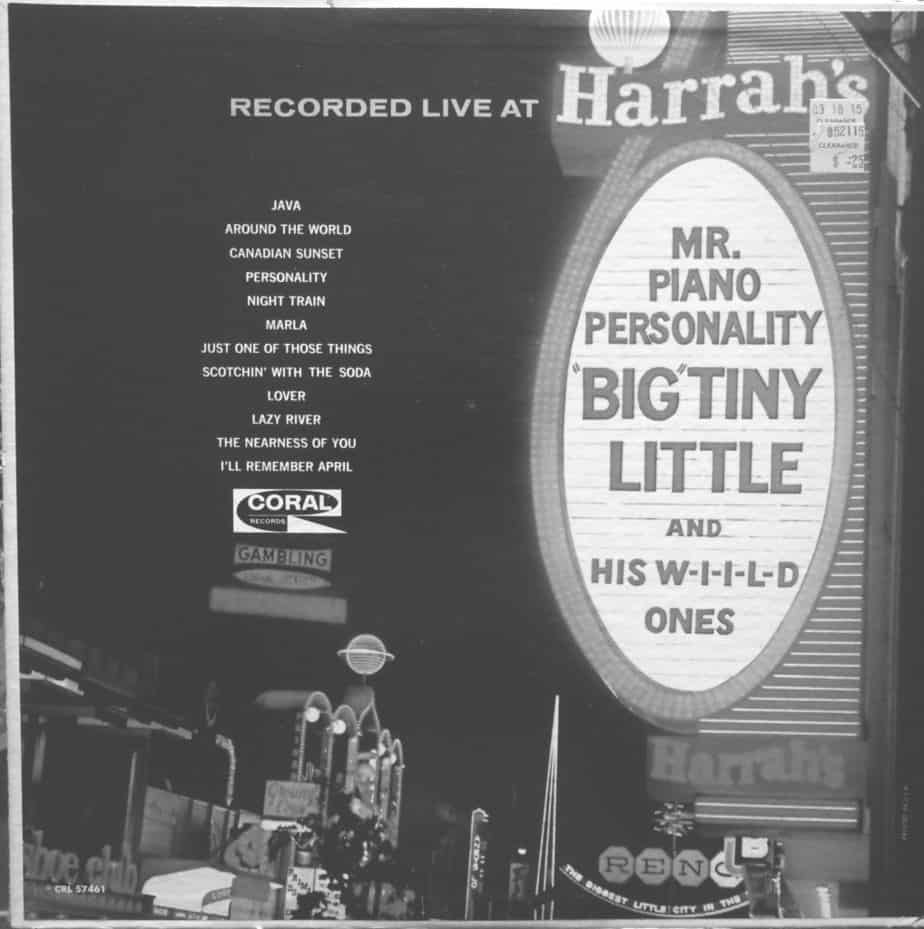

The first couple years of the 1960s seem a bit of a mystery for Virginia City’s honky tonk scene. Clearly the town enjoyed Harry Bruce and a couple other honkytonk pianists. This stood in contrast to the broad decline of traditional jazz in the big cities. And to a shift by Reno and Vegas acts who played ragtime or honky tonk to application of old methods to more modern and eclectic material. Two good examples of this in pianist Big Tiny Little and banjoist Georgette Twain. Each would play both old standards as well as more modern pieces. From 1962 and for decades, Big Tiny Little (August 31, 1930 – March 3, 2010)[68], played ragtime piano in Reno-Tahoe region. During 1964, he recorded a live album with a band at Harrahs in Reno. However, the honky tonk scene was shifting away from downtown Reno. Known as the Queen of the Banjo, Georgette Twain (1925-2016) played banjo across the northern California, Reno, Tahoe and Virginia City region.[69] Both enjoyed long careers.

Smiley versus Lack of Bathing

By 1965, Virginia City hosted honky tonk/trad jazz/ musical groups up and down C St. The idea of projecting a wild west fantasy saloon onto Virginia City may have been inherent to all of these. The “western” image mitigated against perceived “beatnik” corruption, despite a notable effort in that direction. Bob Darch helped popularize ragtime among the young and for talking about Virginia City. A photo shows Swedish ragtime piano player Peter Lundberg visiting the Bucket Of Blood saloon during 1963, having heard about it from Bob Darch. [70]

The 60s pop star Ian Whitcomb credited Darch as a major influence. Whitcomb played ragtime in the blossoming counter-culture scene of the mid 1960s.[71] On youtube, watch Whitcomb perform his 1965 hit “You Turn Me On”[72]. Whitcomb wrote of Darch, “He was the Real Thing In Color”. The sexual reference in the song’s title contrasts the patriotic and authoritarian invocation to God found in Lorne Greene’s “An Ol’ Tin Cup”.

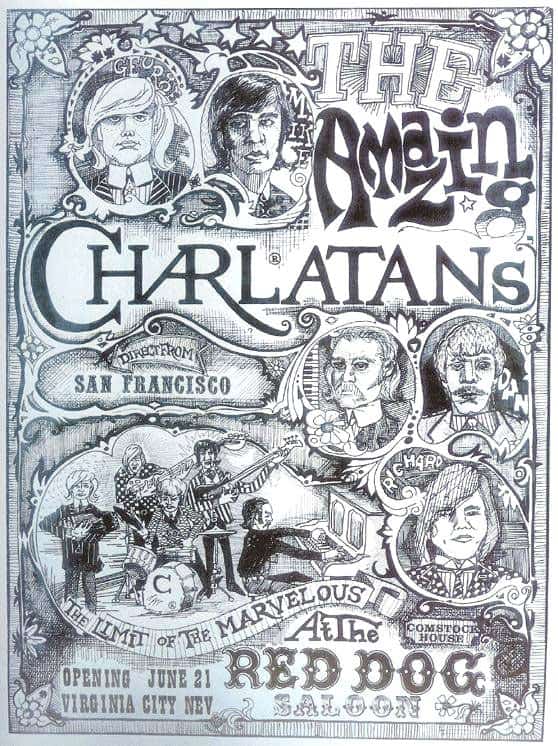

Coming to Virginia City from Juneau, Alaska, Darch seems to have imported the name and idea of, “The Red Dog Saloon”. Conceived as a folk music club with a live western theme and with an vintage saloon vibe[73] in the style of the TV show, Bonanza,[74] During early’65 and probably while living with Peter Kraemer, Zoray Andrus’ son, in the Haight-Ashbury, Tennessee folk musician Mark Unobski heard about Virginia City. To cure his son of dissipation, his father provided him with the space that became The Red Dog Saloon. Unobski recruited the manager of a Berkeley folk music club, Chandler Laughlin III, to find musicians for a folk music venue on C St.. The Red Dog Saloon opened in Virginia City during spring of 1965. It was initially planned that musicians would be brought in who were traveling between coasts and through Nevada. The western saloon folk-music venue mixed Darch’s honky-tonk dive with the new Virginia City energy provided by Bonanza.

‘This is an old western town,’ we’d tell ourselves,” says Chan Laughlin. ” ‘And we’re more old western than anybody else. Just remember, when your feet hit the floor in the morning you’re in a grade B movie. This is that saloon down the street where the manager has his office under the stairs and all the gun hands sit around out front and periodically he comes out and motions a couple of them to ride away and rustle some cows. It’s that place, complete with fancy girls going around bending over tables and the music and people roaring and ordering more drinks and carrying on.’ ”[75]

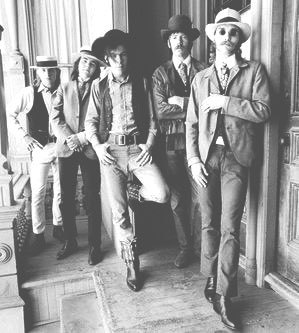

In San Francisco, Laughlin spotted and recruited young men that he mistook for musicians. They arrived in Virginia unintentionally high on LSD. For a couple months, with a sound generally described as “folk-rock”, The Amazing Charlatans played at the Red Dog Saloon in Virginia City—closing on Sundays to host a party of LSD sodden fans.[76] The group’s western-mod attire put new look on Lucius Beebe’s foppish western dandy garb though it isn’t clear how they came upon this—whether in Virginia City or separately.[77] The Charlatan’s early sound was bouncy folk, ragtime, honky tonk—or “jug band” music as often called during the mid-60s. Acoustic/stringed instrument ragtime is still sometimes called “jug band” today in northern California.[78] The Red Dog Saloon quickly became a mecca for what came to be called “hippies”—perhaps so-called after Chandler Laughlin’s nom-de-plume: Travis T. Hipp.

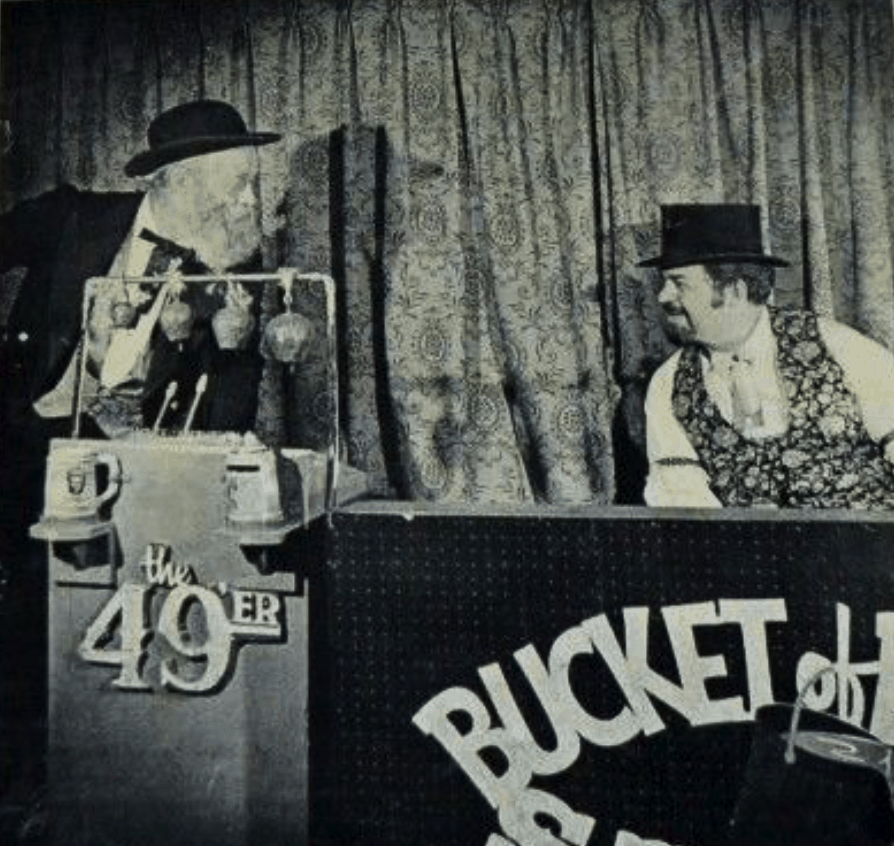

That summer of 1965, Virginia City was hopping with western and ragtime or honky tonk. Harry Bruce played piano up and down C. St.. Mr. Chad played banjo and piano at The Red Garter. At the Silver Queen, Art Rafael played music, is said to have been performing since the 1920s. Merle Koch (“cook”) was tending bar at the Sharon House where he was part owner and sometimes playing piano. He had recorded an album,”Shades of Jellyroll” in 1959. At the Bucket of Blood appeared “The 49ers”: Carol Washburn on single string bass, Norm Jackson on piano and Smiley Washburn on a washboard complete with horns, sirens, whistles, hooters and bells. The “night trick” at the Bucket featured Edna Dunn on piano, Frenchy Brezeau on banjo and Vin Armstrong on clarinet. And, in the midst of all this, the Charlatans were playing The Red Dog Saloon. During August of 1965, the Los Angeles Times described the newbees, failing to reveal that the “frenetic” dancers had taken LSD:

Latest addition to C St.’s musical menu is big on the controversial side, mainly because it is a beat group whose members’ shoulder length hair-dos make the Beatles look like a bunch of crew cuts. All from the Bay Area, they play to a packed house every night at the Red Dog Saloon where the frenetic gyrations of the dancers are as much an attraction as the player themselves. They call themselves The Charlatans.[79]

The Red Dog quickly became too wild for rural Virginia City. Virginia City had a quaint, incidental quality that, in the wake of decades of visits by divorcees and others, seems to have been almost by design. Vin Armstrong’s account of how he came to play music there in 1964 illustrates this:

Hi, Chris – OK, let me try to answer your questions about me in VC:

I was born and raised in Pasadena, CA. I began playing piano by ear in 1956, getting pointers from my grandfather who had learned how to play ragtime from the black players in his Missouri hometown, Slater – and my dad also could play be ear, though he favored a slower, ballad style.

I was 21 years old during the summer of ’64 and I went on a camping trip with a buddy of mine. On July 4th, we’d left Yosemite Nat Park and were coming north on US 395 into Carson City around mid-day. I saw a billboard advertising Virginia City. I thought we should take a detour from our schedule and visit the famous old mining town.

I love Western history and was immediately taken with the old structures in Silver City and Gold Hill as we ascended to road to VC. But neither of us was prepared for the excitement we met upon entering VC. The holiday parade had ended on C Street, but the boardwalks were crowded by festive tourists. We parked somewhere and began walking north on the boardwalk on the west side of C Street.

Just after passing Taylor Street, we came upon a piano sitting on the boardwalk just at the door of The Great Western Saloon. I just had to see if the proprietor would let me play a few tunes – it would be so cool to tell my folks & friends back home that I’d played in VC! I talked to the proprietor, a small, older woman named Bea. She said “go on ahead!”. After playing a a few tunes. Bea asked if I’d be interested in playing piano there for the rest of the summer season. She said she’d line up a room for me. Wow! Well, I was on summer break from college (Cal State LA), and had no special plans. My buddy urged me to go for it, and I did!!!

I stayed in a room across the street, above a “Cowpoke Cones” concession. It was a great arrangement-just had to walk across the street to my piano solo “gig”. I played a daytime shift, as that’s when most of the tourists were around. After awhile Don McBride, proprietor of the Bucket of Blood, also hired me to play an evening or two at the Bucket of Blood. (I believe Norm Jackson was playing piano there week days.) I made sure I had at least one complete day off per week to sightsee and enjoy the Comstock heritage. There was lots going on in VC, Carson & Reno then, as 1964 was the Nevada Centennial. Camel & Ostrich races were a big deal in VC. I rather quickly made several friends to hang out with, and it was just a terrific time.

Not long after I commenced my summer gig, people began urging me to go see Merle Koch (pronounced, Cook), a piano player at the Sharon House. The Sharon House, on Taylor Street between C and B streets, was the finest restaurant in VC. It specialized in Chinese food and was run by Merle and Lin Leong. Merle tended bar there. In the bar area, in addition to the stools, there were a few small circular tables and a small upright piano (an Acrosonic). As mealtime wound down, Merle would entertain the bar customers by playing the piano. I tell you, Chris, other than on records, I had never heard anyone play such wonderful jazz piano as did Merle at the Sharon House. I was awestruck, really. I went ofter to hear Merle at the Sharon House. We became acquainted, and we became friends.

I would learn from Merle that the New Orleans jazz clarinetist, Pete Fountain, had met Merle at a jam session in the L.A. area when Pete was playing on TV with the Lawrence Welk band. When Pete decided to quit Welk (around 1959 or 1960) and open his own jazz club in New Orleans (the Bateau Lounge), Pete asked Merle to come with him. Merle did so, and her spent 3 years with Pete. During that time, he recorded with Pete three albums for the Coral label, in addition to an album on Carousel (later, Southland Records) of piano solos (with a few vocals by N.O. local, Doc Soushon), called, “Shades of Jellyroll”. In around 1963, Pete took his jazz group on the road to Lake Tahoe. Merle took the opportunity to visit Virginia City, and he just loved the town. Soon thereafter, Merle quit Pete to move to Virginia City. More on Merle later.

The Times article mentions Art Rafael on piano at the Silver Queen. Art, a small older man, had a white goatee and wore a black top (stovepipe) hat. The piano at the Queen was elevated on a small bandstand – Art’s perch. I was not impressed by Art’s playing. I don’t think I ever heard him play a complete song. He just sort of dabbled on the keys. But, visually, he was pretty cool. Norm Jackson was OK on piano. Beard and vest and black slacks. Edna Dunn, another piano player, was also around in both ’64 and ’65. She was a heavy woman, hard to guess her age, maybe 35 or 40. She was sweet and pleasant, had a jolly countenance. Passable as a piano player. I think I recall her singing as well. Edna, and many of the other VC entertainers, had off-season gigs across the state line at the gold towns on Highway 49.

At the Great Western Saloon, I started there playing piano on the boardwalk, just outside the entrance. At some point that summer, the piano was brought inside and I played near the bar. The GW was smaller than the Bucket, but customers would linger by the piano to listen, or sit nearby at one of a few small tables to eat food from the kitchen and visit, sometimes listening to what I was playing. I would get song requests sometimes. At the Bucket, I played the rosewood square grand (as you see in that photo). I would sometimes fill-in for one of the other performers, should that become necessary.

As I would be on summer break from college again in 1965, I made plans to return to VC. That summer, Ken and Bea, the proprietors of the Great Western Saloon, got a room for me over the laundromat on north C street. When they were unable to continue to afford to pay me, Don McBride of the Bucket hired me “full time”. This is when I met Frenchy Brazeau, quite a fine banjo player and singer. We often played as a duo. Also, I brought my clarinet with me for this summer, and it came in handy when I was sometimes paired with other musicians (as in the Edie and Ford Hastings photo where you see the clarinet atop the piano). The Bucket participated in a parade in Carson City and hired a flatbed truck to support a dixieland band to advertise the upcoming camel races. I played clarinet in that bend, Harold Wheeler played guitar, Frenchy on banjo, maybe Smiley was on gut-bucket bass.

Most tourists would depart VC before sundown. But the Bucket stayed open the longest of any VC business. The tourists who did linger late often found themselves hanging out at the Bucket, and the Bucket would often stay open after midnight.

Most of the ’64 VC musicians were on hand for summer of ’65. But I want to make particular note of newcomer, “Chad” Chadburn. He was an excellent player, sophisticated harmonically and swinging. He played at the Red Garter Saloon, which at that time was just north of Taylor on C Street, two doors south of the Great Western. Though not of Merle’s caliber, he and Merle were the best jazz musicians in VC that summer. Chad had a teenaged son, Page, who played guitar and made friends with some of the local town’s boys. They all soon began to come and hear me, and I became good life-long friends with one of these boys, Jim Bolander, whose parents ran the Turquoise Shop (located between the GW Saloon and the Red Garter). Another addition was a pianist named, Murray who was known as “Ruffles” for the flamboyant shirts he word. He was an entertainer, not a bad pianist.

The big change was the addition of The Charlatans to the music scene, at the Red Dog Saloon. With the other saloons in town, if they had music, you might hear it a bit as you walked by their entrances. The Charlatans’ amped-up rock flooded the north part of town, every night they played. Their deafening, edgy guitar and vocals were completely out-of-character for VC, which had before generally staged only piano players or small Country music combos. Like their music, the hippie drug culture was not appreciated by the resident town folks.

Merle was still at the Sharon House, and I would try to hear him often. His reputation resulted in many well-known jazz musicians coming up to Virginia City to sit-in with Merle. (Such as trombonist Bob Havens who would visit Merle when he (Bob) was gigging at Tahoe or Reno). I recall hearing cornet player, Ernie Carson, in a wonderful jam with Merle at the Sharon House. Then I had to leave to play a night of piano at the Bucket. Ernie came in a bit later with his horn, and he and I jammed at the Bucket till sunrise!

In the summer of 1966, I got a chance to play in a Dixieland band from California at a lake resort in New Hampshire. I took the opportunity, so didn’t return to VC. In January of 1967 I was drafter into the Army. After my two years of service, I went to work for the County of Los Angeles, staying until my retirement in 2000. Despite my day job, I continued to play gigs on the side – and I am playing still, at age 78.

At some point, Merle got out of the Sharon House business. He played in 1968 at Pardee’s Restaurant in Seattle, but then returned to VC where, with his 2nd wife, Michele, he purchased what he renamed as “The Silver Stope” on north C Street. This was a small, very good dinner house with a bar. It had rocky walls, like a mine tunnel. Merle had a small stage built on which he put a baby grand piano. (Merle also built an apartment house down of “F” street. He had a model train set-up on his second floor and was into Ham radio.) Tending bar and playing piano at the S. Stope until his death from cancer around 1987, the Silver Stope was THE jazz spot in Virginia City. Merle had good musicians from Reno/Carson come up on weekends for Sunday afternoon/evening jam session. Many of these were recorded by Smokey Lawrence (from Carson) on reel-to-reel tape. Merle also recorded several LP’s at the Stope, and he produced an LP of the jazz concert at Piper’s Opera House when Pete Fountain and other great musicians came together there (Merle on piano, of course).[80]

It is said that every Sunday night at The Red Dog, they posted guards at the door to keep out the locals and “The Dog People”, that band’s fans from the Bay Area dropped acid, dancing in a frenzy, and that the band was payed in drugs and guns—from the gun shop next door. When problems with locals multiplied, Unobski padlocked the door.[81] [82] The frenetic dancing and the immediate reaction are reminiscent of the “jazz hysteria” of the 20s. The band’s posters and clothing were efforts to copy the style of the ‘20s.

The nation was fracturing culturally—much as it had during the early 20s. The Amazing Charlatans and their fans, The Dog  People, soon congregated in the Haight Ashbury, helping to inspire a counter-culture scene based on music and psychedelic drugs. In summer of 1966, Unobski tried to obtain a gaming license. However County Commissioners did not want to “mix slot machines with beatniks” or encourage “these types” even though they were assured, “the manner of dress or lack of bathing is beyond our purview.”[83]

People, soon congregated in the Haight Ashbury, helping to inspire a counter-culture scene based on music and psychedelic drugs. In summer of 1966, Unobski tried to obtain a gaming license. However County Commissioners did not want to “mix slot machines with beatniks” or encourage “these types” even though they were assured, “the manner of dress or lack of bathing is beyond our purview.”[83]

Another of San Francisco’s early psychedelic bands, Sopwith Camel, formed late in 1965 and recorded the Haight Ashbury scene’s first nationally popular psychedelic hit with the honky tonk song, “Hello Hello”, featuring a tack piano. The song came out as a single during summer of 1966, well before its release on an album in 1967. The song was written about 1965 and, according to its coauthor, Peter Kraemer, the song had its roots in Kraemer’s 1950s Virginia City Nevada childhood experience of honky tonk piano. At one point, as a child on C St., he held a sign to advertise Ish Kabibble and The Shy Guys, probably as part of Darch’s Jazz Festival and Medicine Show.[84] From ’57 in ‘’60,  Kabibble frequently played in Vegas, Tahoe and Reno. When I spoke with Kraemer, he did not remember the name, “Darch”, only the bustle and zest of the scene.

Kabibble frequently played in Vegas, Tahoe and Reno. When I spoke with Kraemer, he did not remember the name, “Darch”, only the bustle and zest of the scene.

The song’s lyric centered on a sexual double-entendre—“would you like some of my tangerine.” This and the seductive tone of Kraemer’s voice as he sings, seem to carry the mood of Zoray Andrus’ bohemian salon and the local saloons during her time in Virginia City. With a tack piano ragtime solo, the song became a national hit and tied Sopwith Camel to a jug band image that they could never shake as other San Francisco groups quickly moved to a more electronic sound.

Hello hello

I like your smile

Hello hello

Shall we talk awhile?

Would you like some of my tangerine?

I know I’ll never treat you mean

Never knew how I’d meet you

Didn’t know how to greet you

When I saw you look that way

I knew I had to say

Hello hello hello hello

You’ve got pretty hair

Hello hello

Can’tcha tell I care?

Would you like some of my tangerine?

I know I’ll never treat you mean

Always longed to say I love you

Always been too high above you

Now I’m not so far away

Now at last I can say

Hello hello Hello Hello

Many of the early Haight-Ashbury bands seem to have had their roots in the jug-band/folk music sound of early 60s’ Greenwich Village or San Francisco. However, by 1965 or ’66, all sought a more electronic sound—moving well beyond a purely acoustic sound and beyond the label, “beatnik”. Electronic invention flourished and the San Francisco musicians figured out loud out-door concert amplification at a time when the Beatles were stopping their tours due, in part, to the inadequacy of their equipment in outside venues.

Like The Amazing Charlatans, Sopwith Camel did not make an enduring transition to the more complex, languid, contemplative, electronic and drug oriented musical sound that, today or in hindsight, defines as the psychedelic sound of the Haight Ashbury scene. Just as Virginia City was becoming more conservative and even embracing honky-tonk as something from a by-gone era rather than as folk or beatnik music, the Bay Area was radically rejecting what was called “the establishment.” Sopwith Camel did not make the transition. As the first local hit group and with a honky-tonk/jugband sound to that hit, they had been pigeon-holed. And, there was some antipathy toward Sopwith Camel[85] by other Haight Ashbury bands. The biggest rivalry seems to have been with The Grateful Dead whose progenitor shared that early sound—as Mother McCree’s Uptown Jug Champions.[86]

As individuals, the members of Sopwith Camel all sought to make that transition. Internal dissension helped split up the group. Their second album—1973—showed them headed in the right direction—filling out the thinner, bouncier acoustic folk-rock sound with electronics as did other Haight-Ashbury groups. Today, Peter Kraemer remains interested in his saxophone coupled to a synth.

The Red Dog Saloon stayed open. However, the venue’s music during 1966 seems to have been limited to six nights, over three months, of Big Brother And The Holding Company—without Janis  Joplin—brought in from San Francisco to reproduce the party draw begun by the Charlatans. (May 13/14, June 10/11, July 8/9)[87] The PH Phactor Jug Band also performed. All this seems to have been a prelude or diversion while Mark Unobski tried to shift toward making the venue a small casino with 40 slot machines. This fell through in late July when his request for a gaming license was denied due to the saloon’s beatnik atmosphere.[88] That fall the owners ran an ad to sell their “high intensity strobe lights.”[89] Unobski’s interest in the San Francisco sound seems to have ended of necessity—with denial of his application for a gaming license he was faced with a need for the music performed to appeal to ordinary tourists and locals. Feldman later wrote:

Joplin—brought in from San Francisco to reproduce the party draw begun by the Charlatans. (May 13/14, June 10/11, July 8/9)[87] The PH Phactor Jug Band also performed. All this seems to have been a prelude or diversion while Mark Unobski tried to shift toward making the venue a small casino with 40 slot machines. This fell through in late July when his request for a gaming license was denied due to the saloon’s beatnik atmosphere.[88] That fall the owners ran an ad to sell their “high intensity strobe lights.”[89] Unobski’s interest in the San Francisco sound seems to have ended of necessity—with denial of his application for a gaming license he was faced with a need for the music performed to appeal to ordinary tourists and locals. Feldman later wrote:

In my impression, formed in 1967, that Mark Unobski & friends never tried to “fit in”! Mark was given the place as a birthday present from his parents, who, I heard, were at their wit’s end to try to give him a focus for his life, which was fairly dissipated at that time. VC was used by Mark et al as a background for their wild west fantasies. Basically, they considered locals as squares, or hicks, many of whom they found annoying. The Red Dog was used as a chic hideaway for the SF hippie culture. It was a perfect place to indulge in drugs (they made fun of the local sheriff because he didn’t know how to recognize them), and dress up in Victorian clothes (two shops in the City had recently held “going out of business” sales and everyone in the area loaded up on cheap Victorian outfits, as shown in Charlatan publicity pics.)

The Red Dog was an extension of San Francisco, nothing more, nothing less. Friends and hipsters made the drive from the City on weekends to party and stay there and nearby hotels. Guards were posted at the doors to keep the locals out! Inside were punch bowls spiked with acid, and silver trays of joints, along with gourmet dinners prepared by Jenna Nichols. [90]

During summer and fall of ’67, a group of folk musicians, The Scragg Family—Peter Feldman and friends— worked as the house band at the Red Dog Saloon, living upstairs and playing a mix of acoustic honky tonk, Carter family songs and folk songs. Their music represented a blend of the blues, jug band and old time styles increasingly popular among younger musicians reviving American roots music on both coasts.[91] They never achieved the fame of the Charlatans or Big Brother And the Holding Company. Today, that fame obscures the evidence that The Scragg Family proved more popular among locals and ordinary visitors to Virginia City than any of the famous psychedelic groups. The Scragg Family later spent some time playing in the bar at nearby Sutro.

The two years of psychedelic rock at the early Red Dog Saloon may not be simply an idiosyncratic or peripheral chapter in the overall story of honky tonk. Inspired by Virginia City’s honky tonk scene and then, immediately, rejecting the locals and the local scene to create a loud electric, drug fueled folk-rock and then rock genre, carefully remembering later nothing but their own invention, indulging the  double-entendre and theatrics of honky-honk without preserving its musical substance, casting aside Sopwith Camel because they enjoyed one honky tonk hit while the overall Haight-Ashbury sound increasingly revealed in electronics, the bands of the San Francisco sound betrayed the deep ambivalence the nation has always felt about the dance house and its musical lineage, honky tonk music. Frequently, histories of jazz origins have sought some kind of pure ethnic origin and hence some kind of simple cultural meaning. In contrast, like the story of jazz hysteria in Reno during the 1920s and ‘30s from which it grew, Virginia City’s honky tonk heyday—the 1940s into the 1980s—derived not so much from clear and noble intentions as from ongoing cultivation of a ragged musical form when it stayed close to its low origins.

double-entendre and theatrics of honky-honk without preserving its musical substance, casting aside Sopwith Camel because they enjoyed one honky tonk hit while the overall Haight-Ashbury sound increasingly revealed in electronics, the bands of the San Francisco sound betrayed the deep ambivalence the nation has always felt about the dance house and its musical lineage, honky tonk music. Frequently, histories of jazz origins have sought some kind of pure ethnic origin and hence some kind of simple cultural meaning. In contrast, like the story of jazz hysteria in Reno during the 1920s and ‘30s from which it grew, Virginia City’s honky tonk heyday—the 1940s into the 1980s—derived not so much from clear and noble intentions as from ongoing cultivation of a ragged musical form when it stayed close to its low origins.

The honky tonk scene in Virginia City continued. A clipping shows an aging Harry Bruce still at the piano.

Rags, Ballads and Blues

Through the 60s, 70s and 80s, Virginia City became a Mecca for honky tonk as an alternative. Though The Charlatans did proved a bit too far out for the old mining town, C Street long echoed with a ragged assortment of honky tonk, ranging from the zany to the sublime.

At the zany end of the spectrum, The 49ers— Norm Jackson and Smiley Washburn— played at the Bucket of Blood for at least six years and recorded an album about 1968.[92] The percussionist, Smiley Jackson, fronted their show. He had been a silent movie stunt man and now drove a mule up and down C street—playing the part of prospector—when not playing music. Their album included old standards and an original piece: “Silent Movie Days.”

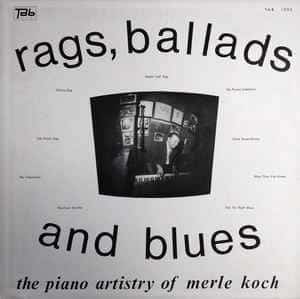

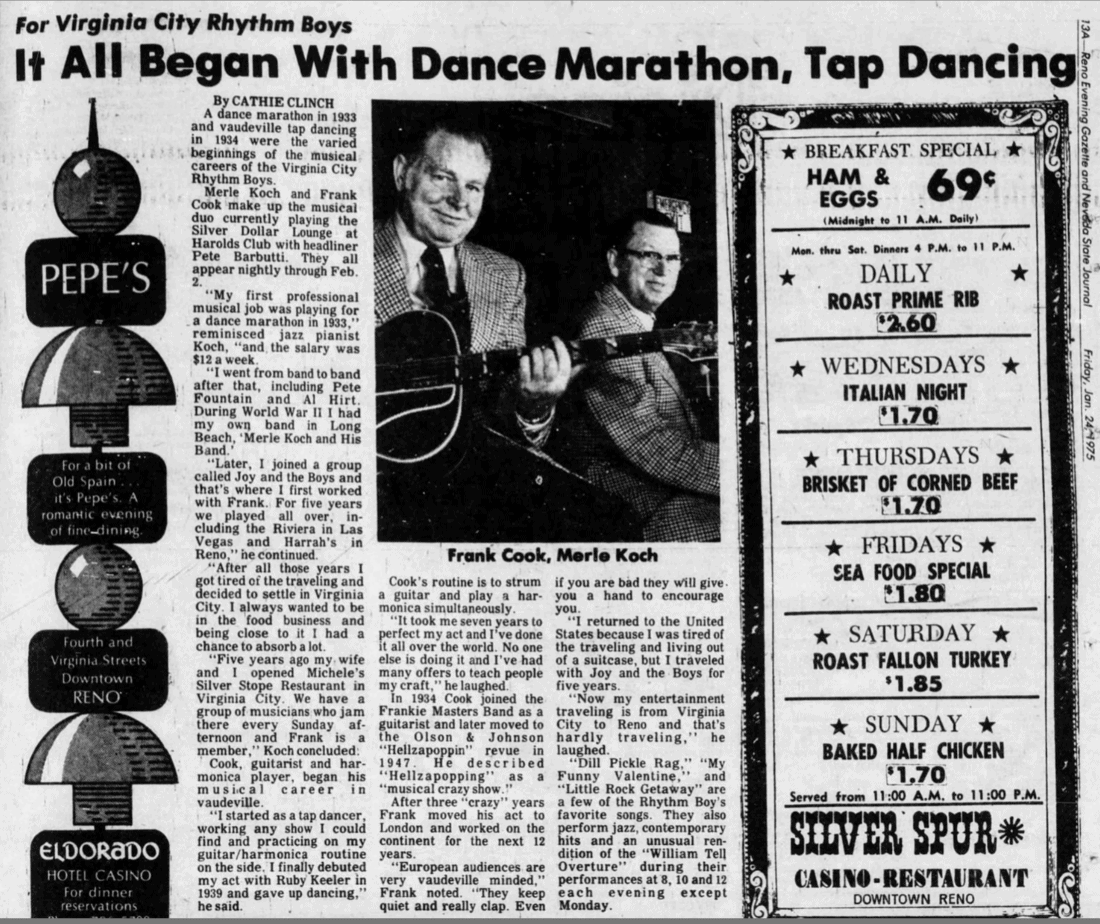

About summer of 1971, after several years playing sporadically at The Sharon House, dixieland pianist Merle Koch (“cook”) (1914-1987) converted The Silver Stope, an antique store, into a dixieland/trad-jazz club—Michelle’s Silver Stope. Koch had played with Pete Fountain in New Orleans during the late 1950s.[93] In 1959, he recorded his album “Shades of Jelly Roll” with Doc Souchon providing some vocals. While touring Lake Tahoe (1963?) with Fountain, he visited Virginia City and decided to settle there—a respite from the performance/bar scene. Jazz guitarist Frank Cook (1915-1979) moved to Virginia City about 1973 and with Koch played as the The Virginia City Rhythm Boys[94]—performing sometimes in Reno and often at the restaurant until Cook’s death in 1979.[95] Based on Koch and Cook’s playing and the friends they attracted, by 1975, Michelle’s Silver Stope had become  famous.[96] At the Sunday jams, professional musicians in orchestras and bands that were appearing in Reno and Tahoe would come up to the club, presumably enjoying a freedom the showroom gigs did not afford.

famous.[96] At the Sunday jams, professional musicians in orchestras and bands that were appearing in Reno and Tahoe would come up to the club, presumably enjoying a freedom the showroom gigs did not afford.

By 1970, Reno’s trad-jazz or honky-tonk scene had began to wane—signaled in 1972 by the close of The New Orleans Jass Club of Northern Nevada.[97] However, at the same time, Lawrence Welk band musicians, particularly Bob Havens, were showing up in Virginia City for the modern jazz jams at the Silver Stope. Where they were tied to arrangements in the paid gigs, at The Silver Stope they could cut loose. At times, Koch took his dixieland group into Reno. [98]

In 1973, at the end of his career, Roderick Malcolm Johnston

“Red” Watson began playing banjo at the Bucket Of Blood in Virginia City. He played there 15 years.[99] Born 1906 in Scotland, Red grew up in Canada where, beginning in the 1920s, he worked as a cowboy and played banjo in vaudeville. After WWII, he toured into the U.S, playing with Hoot Gibson, Roy Rogers and others. From about 1955 through ’59, Red played with Mickey Finn, out of San Francisco.[100] When Finn opened club in San Francisco, Red became his partner until 1966 when he went to Las Vegas to perform.[101] He regarded the Bucket of Blood as a retirement gig.[102] He died at the age of 101 in 2007.[103]

Daniel Yuhasz played a gut bucket that he’d painted at the auto repair shop where he worked.

During 1976, the Reno musician strike and associated closing of showrooms and lounges in Reno prompted owners to permanently cut back the number of professional musicians coming into the area. Band leaders had been accustomed to doing hand-shake deals with the owners of casinos—men for whom the show-room was not a money maker so much as a sign of status and source of joy. By the mid 70s, the old line owners were selling out to corporations whose bean-counters saw showroom space purely as a potential revenue sources. With the orchestras gone and music  reduced in the lounges, they installed in-house girly shows.

reduced in the lounges, they installed in-house girly shows.

A highly skilled “dixieland” or honky tonky pianists, Koch recorded seven albums, several in Virginia City. His “Rags, Ballads And Blues” contains “The Silver Stope Stomp”. While a number of the pieces are moody jazz pieces, the “Stomp” is a lively one part rag, apparently intended to invoke the place. Among the seven albums he recorded, Merle Koch recorded live albums at the Silver Stope, Merle Koch and Eddie Miller at Michele’s Silver Stope Virginia City in 1980, one during 1982[104] and two in 1983[105]. For the 100th anniversary of the place, Pete Fountain recorded live at Piper’s Opera House in Virginia City in June of 1983 with Koch, Eddie Miller, Bob Miller and Nick Fatool.[106] A month later, in  July, Fountain recorded the album, “Do you know what it means to miss New Orleans?” with Koch, Bunky Jones and VJ Bourgeois at the Silver Stope.[107]

July, Fountain recorded the album, “Do you know what it means to miss New Orleans?” with Koch, Bunky Jones and VJ Bourgeois at the Silver Stope.[107]

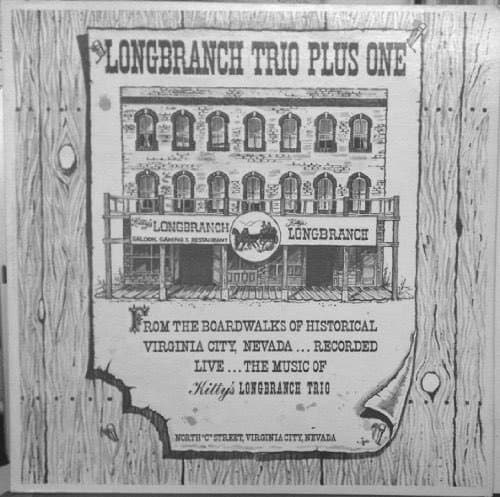

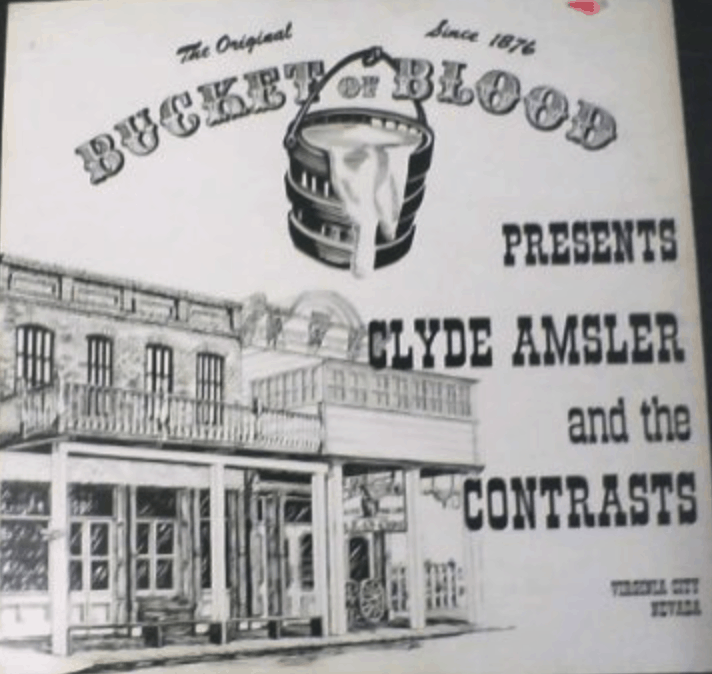

Local lounge musician, Clyde Amsler recorded at Kitty’s Longbranch—formerly the site of The Red Dog Saloon— and at The Bucket of Blood. Harry Bruce continued to play piano in Virginia City until about 1990. At one point, he played at the Union Brewery with Jack Curran on the banjo, Elmer Von Scheibel (“Spoons”) on the spoons and the old prospector Bad Water Bill on the gut bucket. Here’s Jack Curran as he sat in with the Reno Banjo Band during the mid 60s. A surveyor, engineer, politician and author, Curran played Dixieland banjo in Virginia City into the 1990s.

The Silver Stope ceased to be a jazz club by 1987. A 1986 video from inside the club shows Koch playing shortly before his death. Perhaps in response to this, in 1987 and for three years Bucket of Blood banjoist Dave Wierbach and pianist Doug Davies held a Ragtime World’s Fair in Virginia for three years—for all practical purposes the climactic end of the era. [108] [109] Wierbach recorded a banjo album in 1959. He had played with Lu Waters and Turk Murphy.

Michelle’s Silver Stope continued with Sunday jams until about 1984. Banjo player Dave Wierback and  pianist Doug Davies This included a short-lived, local Ragtime Orchestra.[110] In 2000, Virginia City Tourism attempted to revive the

pianist Doug Davies This included a short-lived, local Ragtime Orchestra.[110] In 2000, Virginia City Tourism attempted to revive the  old-style jazz scene.

old-style jazz scene.

The scene continues at this writing mostly with banjoist Gary Greenlund who started playing in Virginia City in 1975 and pianist Squeek Steele. Over the years, Virginia City ragtime pianist Squeek Steele has recorded about 15 CDs. She is the last of the old-tine honky tonk pianists on the Comstock, performing at the Bucket of Blood and The Gold Hill Hotel.

My jug band, The Honky Tonk Bums—with veteran ‘20s style clarinetist Kid Allen—has played off an on in Virginia City at the Canvas Cafe for several years. Generally, we find that no one in Virginia City remembers its honky tonk history. However, it’s a great place to play.

Part IV. Epilogue

This history had concluded with a detailed look at Virginia City, attempting to understand why, while the nation turned its back on low, experiential music, for about 20 years, honky tonk managed to thrive on the Comstock.

The honky tonk of the 1920s revived the low dance house or honky tonk of the 1880s. Based on the “dance house” the early honky tonk was a mixed race establishment. In the far West, it appears to have develope “ragged” styles of tune performance as early at the late 1850s. The 1890s saw exclusively African American honky tonks as (often racist) polite society sought to stamp out the low dance house. The repression failed and, with “jazz” the low establishment—the honky tonk returned. In Reno this accompanied an official embrace of the broad sin industry unlike anything else across the nation.

With jazz and beginning with “hot ragtime” after about 1910, bands with horns replaced the fiddle of the early honky tonk. Though regarded as low and sinful, honky tonky music possessed a technical complexity that did not survive WW2. “Jazz” underwent a a systematic elevation—its music and history reshaped to reflect a variety of high cultural needs.

Ironically, beginning during the 1940s but memorialized during the 1950s, the conversion of “honky tonk”—of the low, mixed race dance house with exhibition dances and stepped based social and couple dances—into a country western trope mirrors a general decline in lyric and harmonic coherence in American music. At the same time, particularly after WW2, the idea of “folk music” as something primitive and close to the earth emphasized a simplicity to “country” music that carried over into “rock” music during the 1970s.

A mournful seriousness and winking now pervades “American” music of all kinds. The seriousness derives from a presumption, created by critics and then adopted by the rockers of the baby boom, that music should be relevant or say something. And then we should sit and think about it rather than learning to dance in time. The winking comes as, ever since the early 1970s, mainstream musicians have increasingly decorated their ponderous crashing and droning with noises and ideas that key into a cultural critique that constantly reinforces social relevance as a definition of quality.

The low “dance house” or, as later named, the honky tonk or cabaret faded at the end of the 1950s with the decline of true jazz—by then dismissed as “the old stuff”, “traditional jazz”, or “dixieland.” At the same time, hotel casinos replaced ballrooms and cabarets in Reno. The history of jazz hysteria in Reno is a lost microcosm of a larger, forgotten story. Neat, cultured labels have combined with racial and economic assumptions to obscure the fundamental war between sin and respectability that has defined American music since its beginnings.

-

Post War Bohemians of Northern Nevada, Univ. Of Nevada Press, Reno. A booklet providing an excellent summary of the artists and their works. ↑

-

http://www.loc.gov/collections/static/interviews-following-the-attack-on-pearl-harbor/articles-and-essays/biographies/ ↑

-

Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada)22 Aug 1939, TuePage 14 ↑

-

https://bucketofbloodsaloon.com/history/mcbride-and-sons/

See the Roar and the Silence: A History of Virginia City and the Comstock Lode

By Ronald Michael James. See Songs of the Western Miners

Duncan Emrich

California Folklore Quarterly

Vol. 1, No. 3 (Jul., 1942), pp. 213-232 ↑

-

See article he later wrote in Propaganda folder, his papers. https://www.american.edu/library/archives/finding_aids/emrich_fa.cfm ↑

-

Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada) 12 Sep 1958, Fri Page 23. Played the Union Saloon—Peter KRaemer interview November 16, 2018

Also see: http://silvercityreads.blogspot.com/2018/02/finding-silver-city-poet-irene-bruce.html ↑

-

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Freddy_Nagel ↑

-

Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada)

- 12 Jun 1942, Fri

- Page 22

- July 1942 issue of Desert Magazine p. 39

-

Italo Gavazzi interview p. 415-416. The Italian AmericanExperience in Northwestern Nevada, oral history. University of Nevada. ↑

-

Into the Fray: How NBC’s Washington Documentary Unit Reinvented the News

By Tom Mascaro

p.85 ↑

-

Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada)

- 07 Feb 2018, Wed

- Page B3

Mitchell, Bill. “A Visit with Harry Bruce, with Some Light on Euday Bowman.” TheRag Times 15(January 1968):56. (reprinted from Jazz Report53 (1966):n.p.). ↑

-

Clipping of dancers Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada)

- 10 Dec 1965, Fri

- Page 11

-

Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada) 15 Apr 1948, Thu Page 4 ↑

-

Green Bay Press-Gazette (Green Bay, Wisconsin) 10 Jul 1954, Sat Page 9 ↑

-

Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada) 03 Sep 1949, Sat Page 3 ↑

-

The Delta advertised a “music hall” for a time but these ceased by 1957. ↑

-

Obit: https://missourigravestones.org/view.php?id=779621 ↑

-

Nevada State Journal (Reno, Nevada)

- 12 Apr 1953, Sun

- Page 7

-

photo Hagemeyer, Johan, 1884-1962, photographer

1947 https://calisphere.org/item/ark:/13030/ft35800553/

Mark Twain saloon opened 1946, Andrus present. Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada) 17 Aug 1946, Sat Page 3 ↑

-

Age based on article: The Los Angeles Times (Los Angeles, California)

- 24 Sep 1962, Mon

- Page 33

- Her death mentioned: aGE 91 The San Francisco Examiner (San Francisco, California)

- 10 Nov 1983, Thu

- Page 49

-

The Morning Call (Allentown, Pennsylvania)

- 24 Oct 1965, Sun

- Page 64

-

The Morning Call (Allentown, Pennsylvania)

- 14 Sep 1962, Fri

- Page 3

- HIS DEATH:

- Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada)

- 18 Aug 1953, Tue

- Page 11

-

Peter Kraemer interview at The Canvas Cafe November 16, 2018 ↑

-

Santa Cruz Sentinel (Santa Cruz, California) 24 Jan 1982, Sun Page 22

The saloon reopened in 1954 Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada)

- 19 Jul 1954, Mon Page 5

- Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada)

- 15 Jul 1954, Thu Page 17

- Later she lived in Reno. Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada)

- 04 Aug 1972, Fri Page 34

-

Peter Kraemer Interview Mar.1, 2021 ↑

-

Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada)03 Jul 1954, Sat Page 3 ↑

-

Sheet music courtesy of Wendell Newman, Nevada State RR museum. This would have been Coral USA (made in Holland) 78RPM shellac. https://ipfs.io/ipfs/QmXoypizjW3WknFiJnKLwHCnL72vedxjQkDDP1mXWo6uco/wiki/Coral_Records.html

No record copies yet found. Jack Brooks lyricist. Songwriter (“Ole Buttermilk Sky”, “That’s Amore”), composer and author, he came to the US in 1916 and wrote special material for Bing Crosby, Fred Allen and Phil Harris. He also wrote material for the Armed Forces Radio Service’s “Command Performance”. Joining ASCAP in 1946, his chief musical collaborators included Hoagy Carmichael, Walter Scharf, Walter Schumann, Harry Warren, and Serge Walter. His other song compositions include “I Can’t Get You Out of My Mind”, “Once Upon a Dream”, “It’s Dreamtime”, “Song of Scheherazade”, “You Wonderful You”, “Look at Me”, “Saturday Date”, “Just for Awhile”, “Is It Yes, Or Is It No?”, “Who Can Tell?”, “Lonesome Gal”, and “Am I in Love?”.

Photo shown here from Daily News (New York, New York)

- 16 Jul 1949, Sat

- Page 59

-

Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada) 04 Sep 1954, Sat That same year Ferre played the Marshall in Rocky Jones Space Ranger and the Silver Needle in the Sky (May 29, 1954) Film credits: https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0274248/ ↑

-

I have been unable to find the actual record. I spoke with the Welk estate copyright agent in Los Angeles and they contacted Larry Welk. Neither knew about the song or could find mention of it. ↑

-

Colorado Springs Gazette-Telegraph (Colorado Springs, Colorado)

- 11 Jan 1970, Sun

- Page 73

-

Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada)

- 04 Aug 1972, Fri

- Page 34

-

h Santa Cruz Sentinel (Santa Cruz, California)

- 24 Jan 1982, Sun

- Page 22

-

The Inter Ocean (Chicago, Illinois) · 24 May 1903, Sun · Page 20 ↑

-

https://syncopatedtimes.com/bob-darch-saving-sedalias-ragtime-heritage/ ↑

-

Casper Star-Tribune (Casper, Wyoming) 07 Aug 1958, Thu Page 5. This article states he played in Las Vegas. I can find no record of that. He probably told the reporter “Nevada” and this got changed to Las Vegas. Or he lied. ↑

-

Italo Gavazzi interview p. 415-416. The Italian AmericanExperience in Northwestern Nevada, oral history. University of Nevada. ↑

-

Fortune Magazine, Sept. 1955, p. 105-106, “Alaska: The Last Frontier” by Richard Austin Smith. The leather strip is visible in this shot from Florida, probably around 1958. ↑

-

((Interview with Jeff Beaumont who knew Murphy and Water while learning to play dixeliand during the late 60s. ↑

-

Fort Lauderdale News (Fort Lauderdale, Florida) 29 Jan 1960, Fri Page 65 ↑

-

A Guide to the Notorious Bars of Alaska: Revised 2nd Edition

By Doug Vandegraft ↑

-

Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada) 02 Jul 1956, Mon Page 3 ↑

-

A Guide to the Notorious Bars of Alaska: Revised 2nd Edition

By Doug Vandegraft ↑

-

Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada) 06 Sep 1957, Fri Page 26 ↑

-

Reno Gazette-Journal (Reno, Nevada) 06 Sep 1957, Fri Page 20 ↑

-

Memoir emailed to author by Pete (Merwyn) Bogue, Mar 8, 2021: 03/07/21

Dear Chris Bayer,