-See more books by CW Bayer at www.nevadamusic.com

When you first open this page, give it several minutes to load. Use a modern computer. Thank you for taking a look!

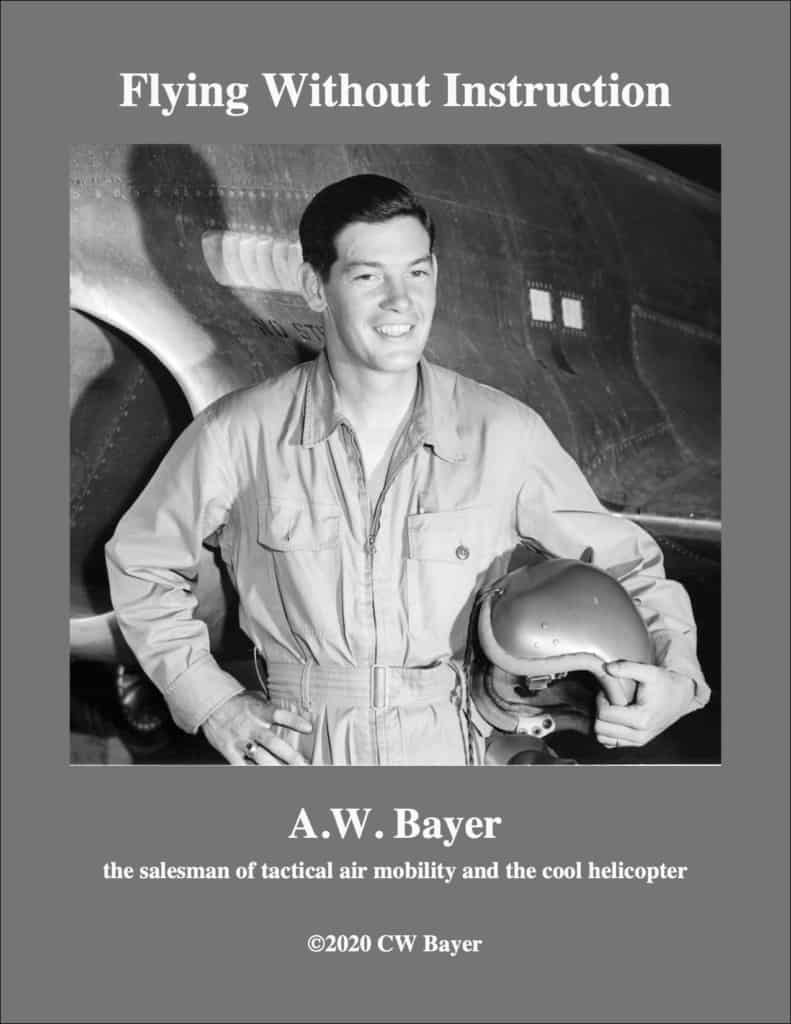

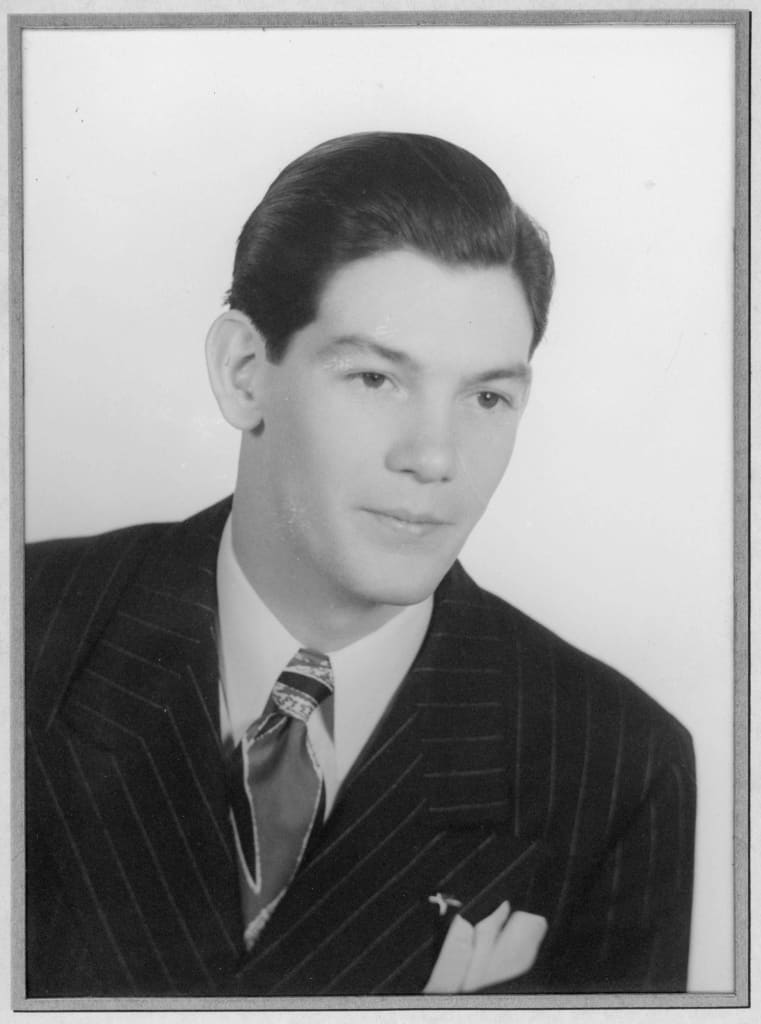

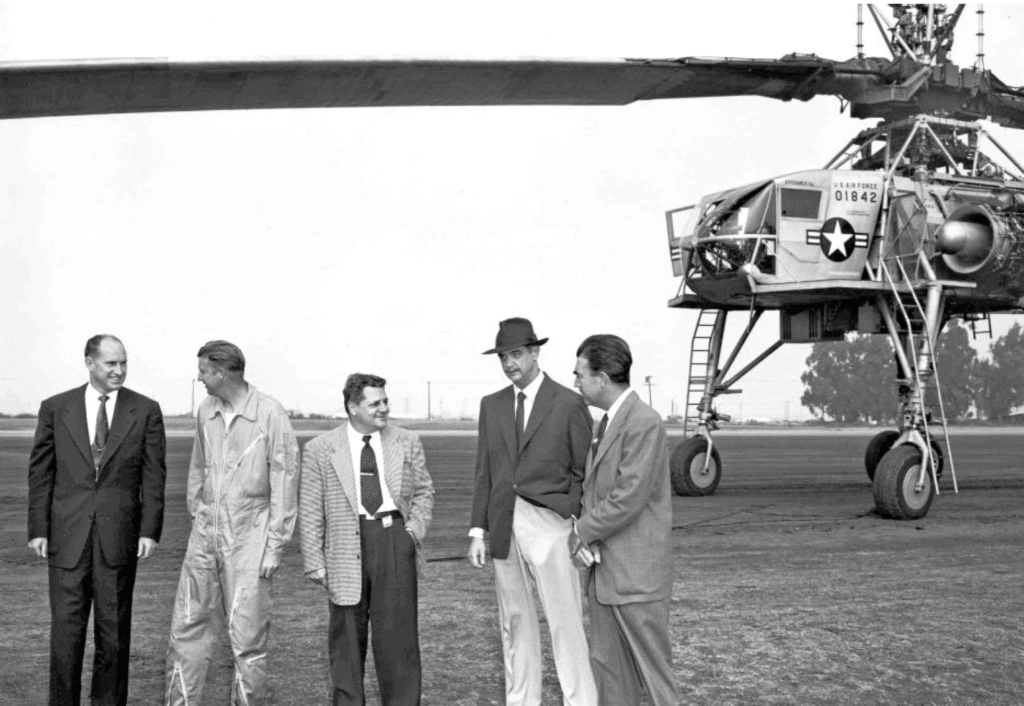

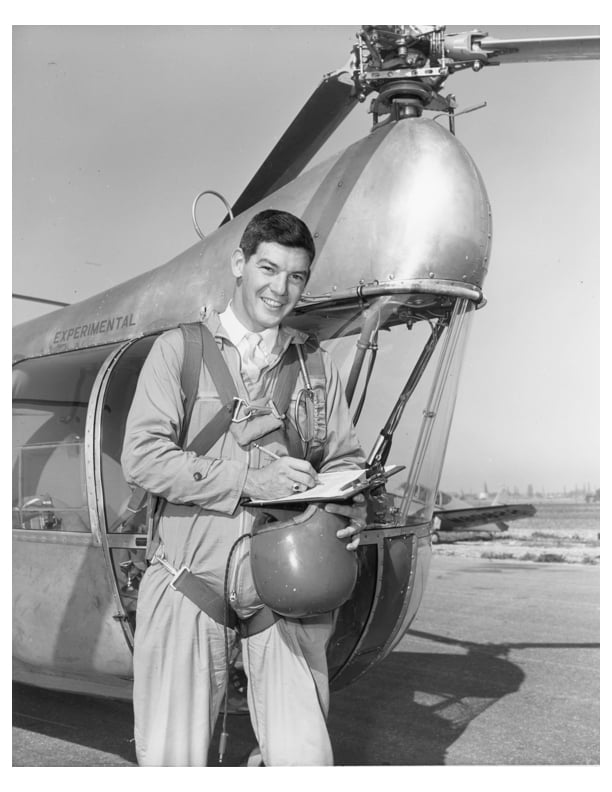

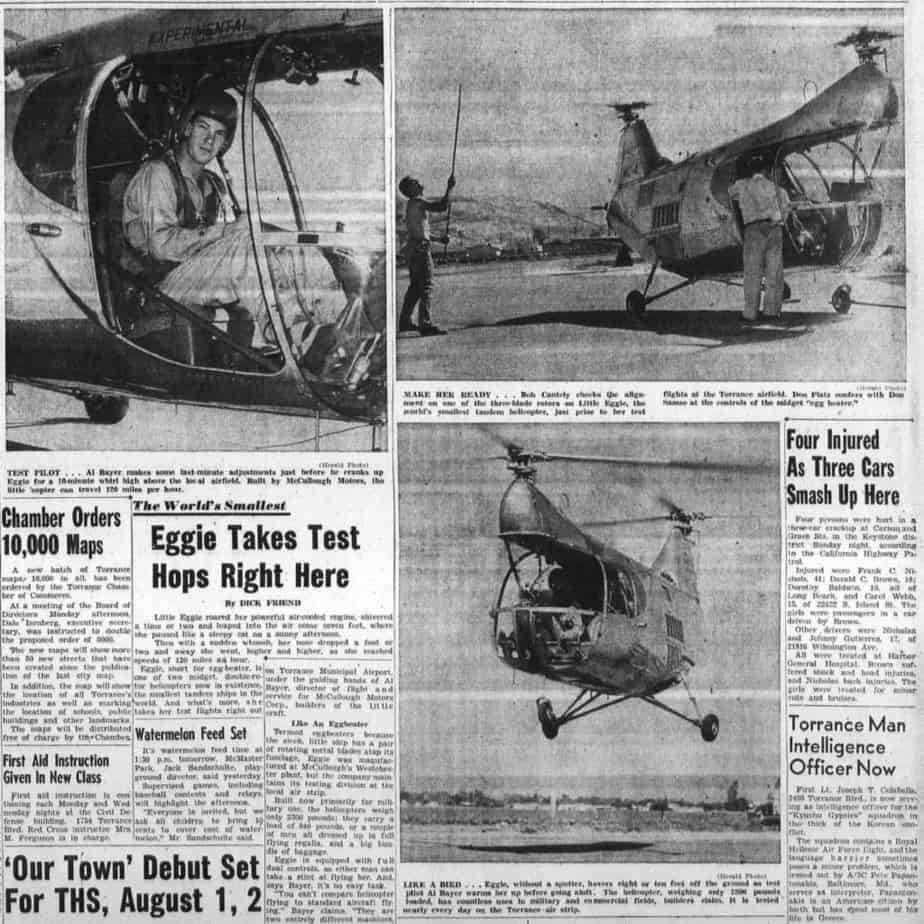

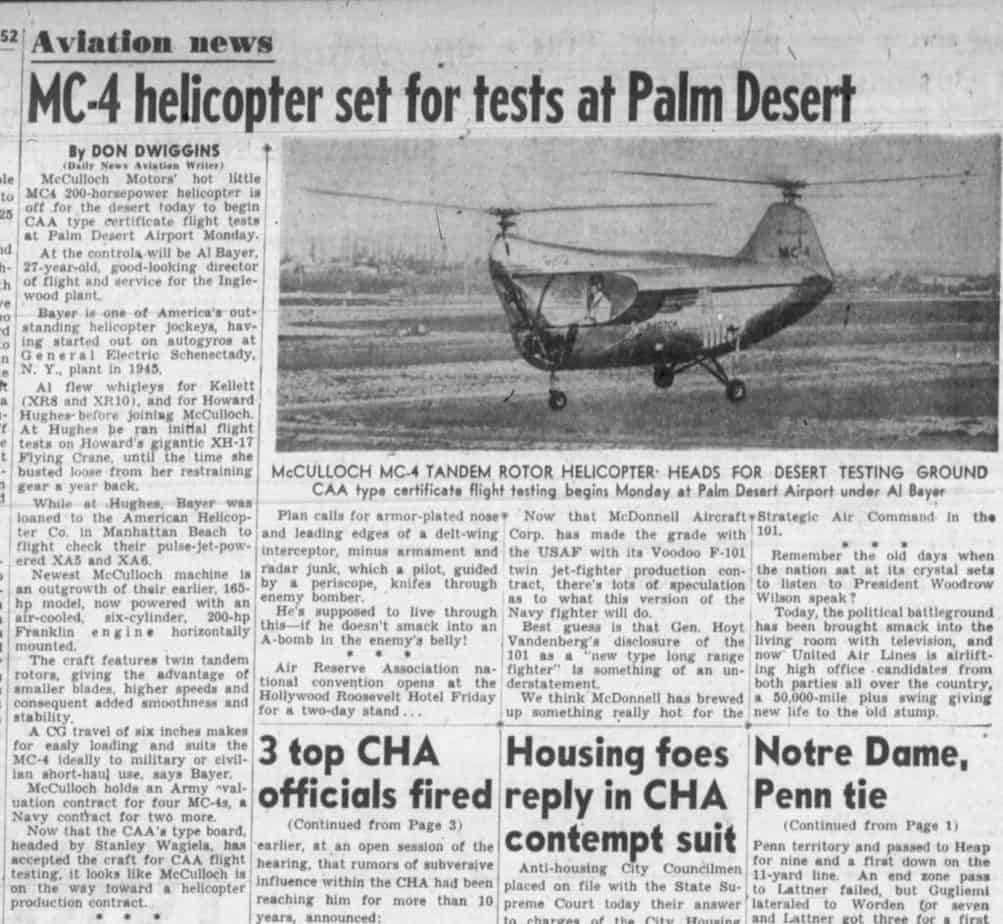

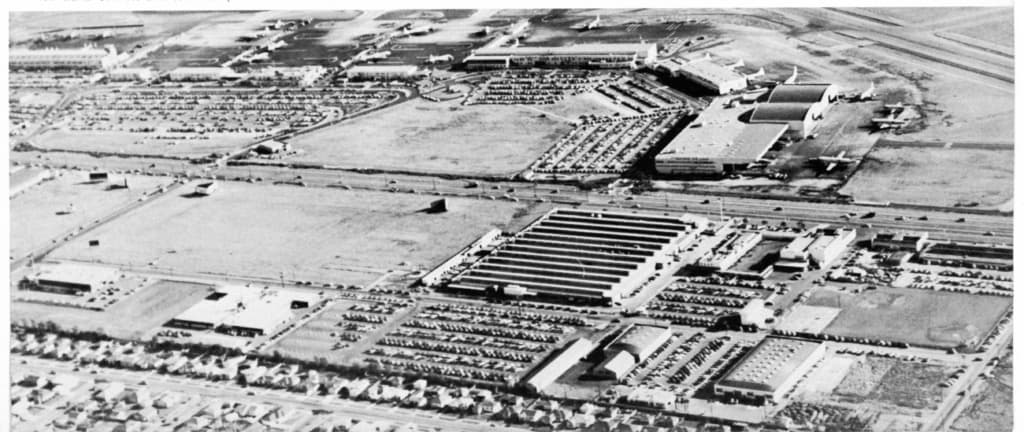

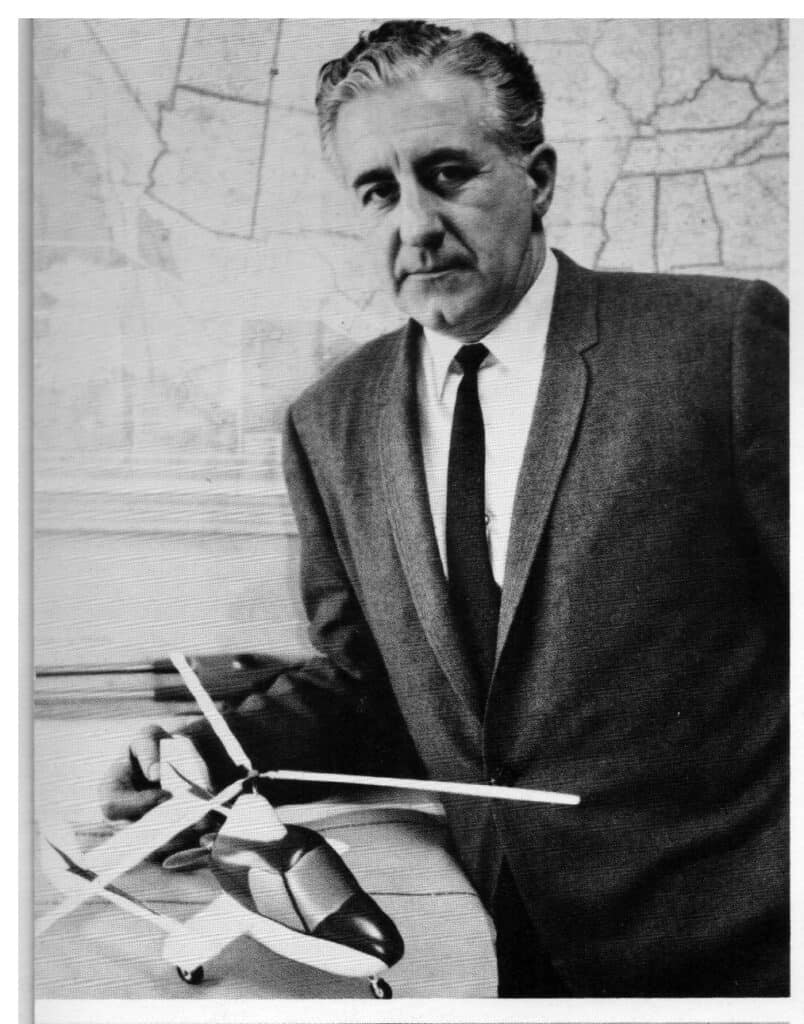

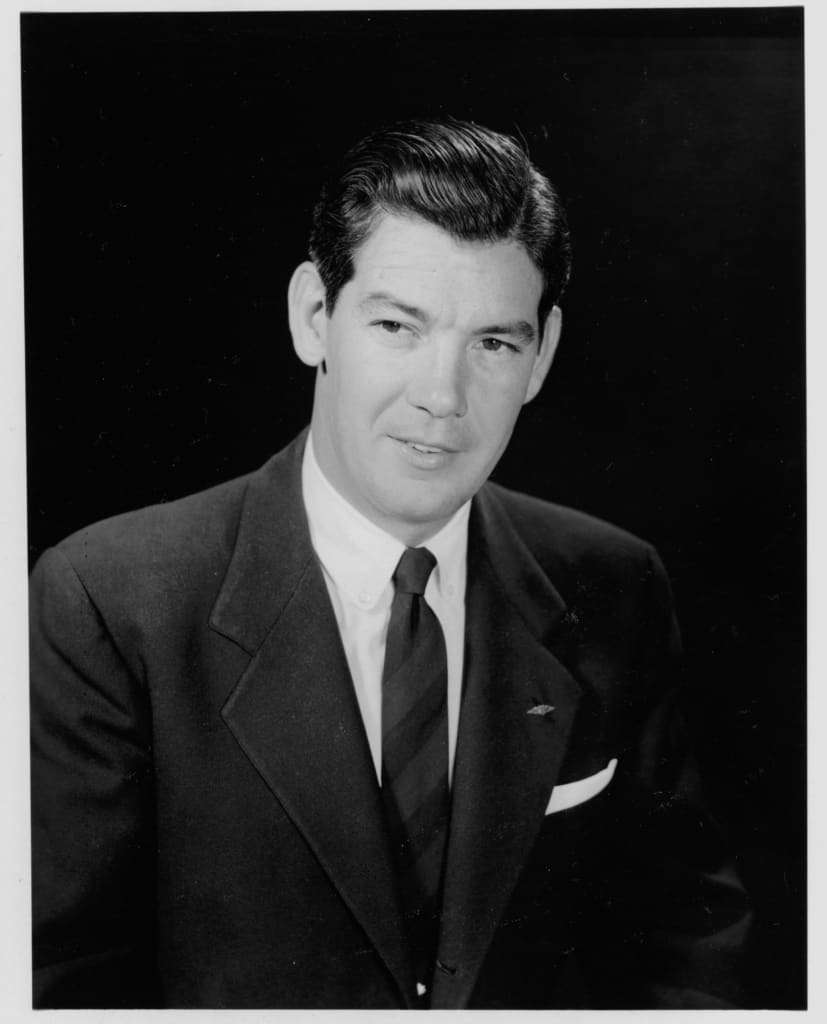

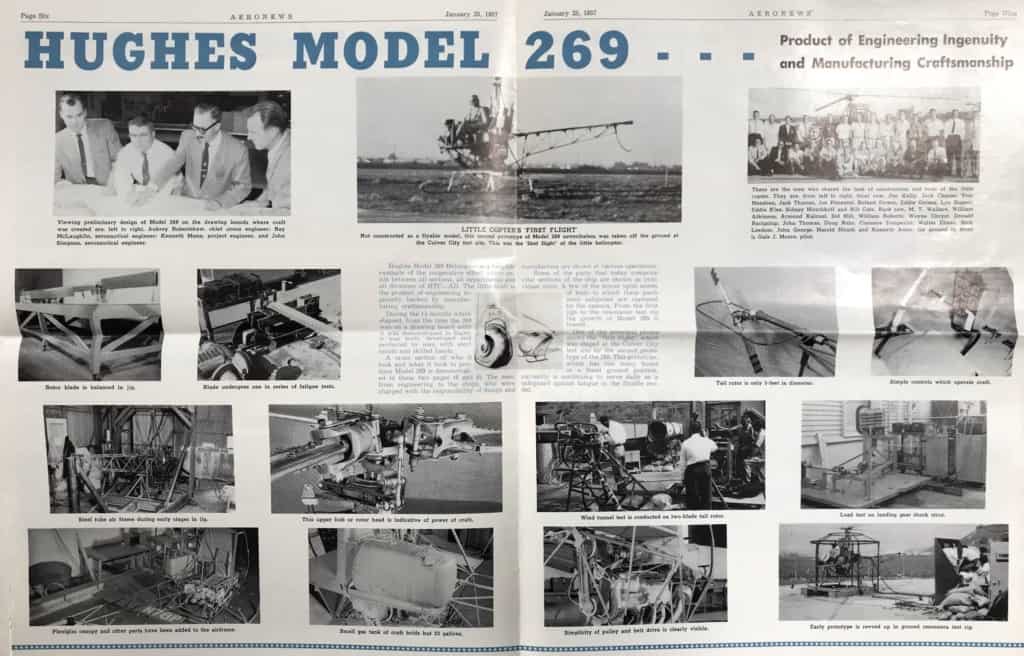

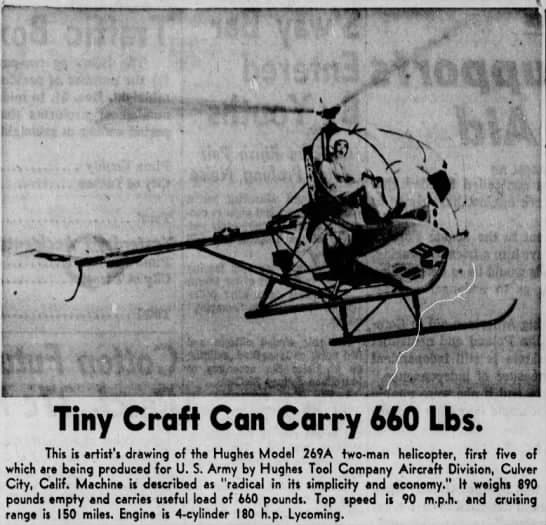

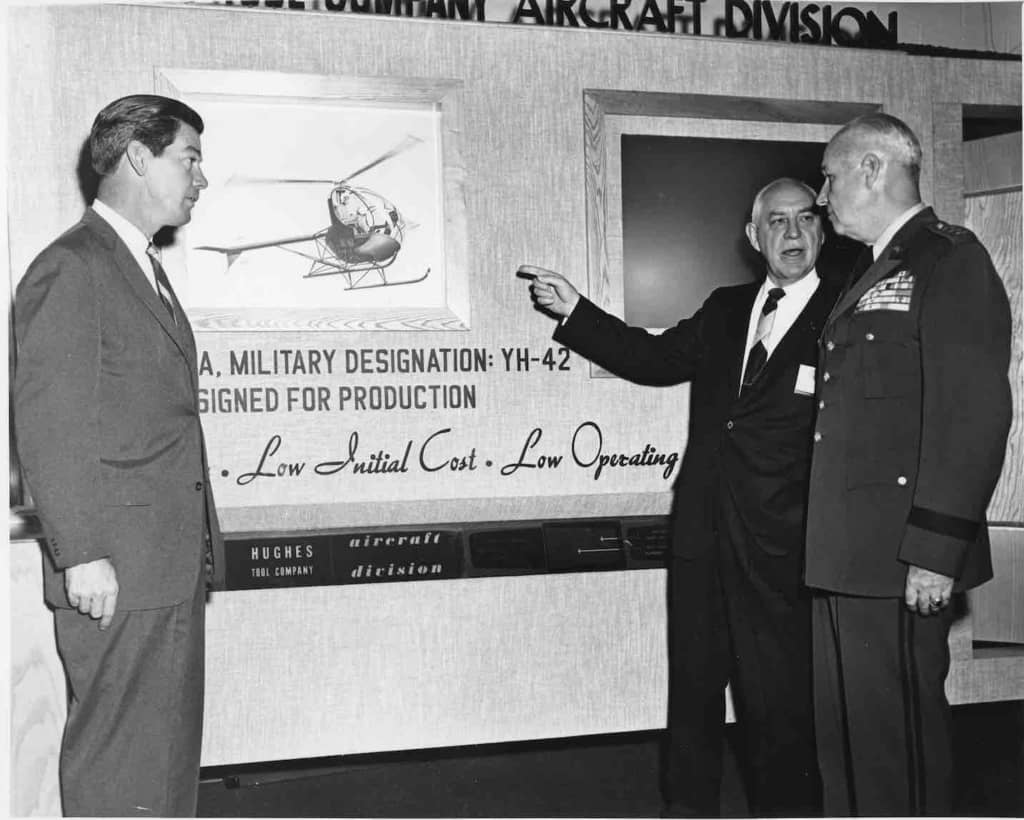

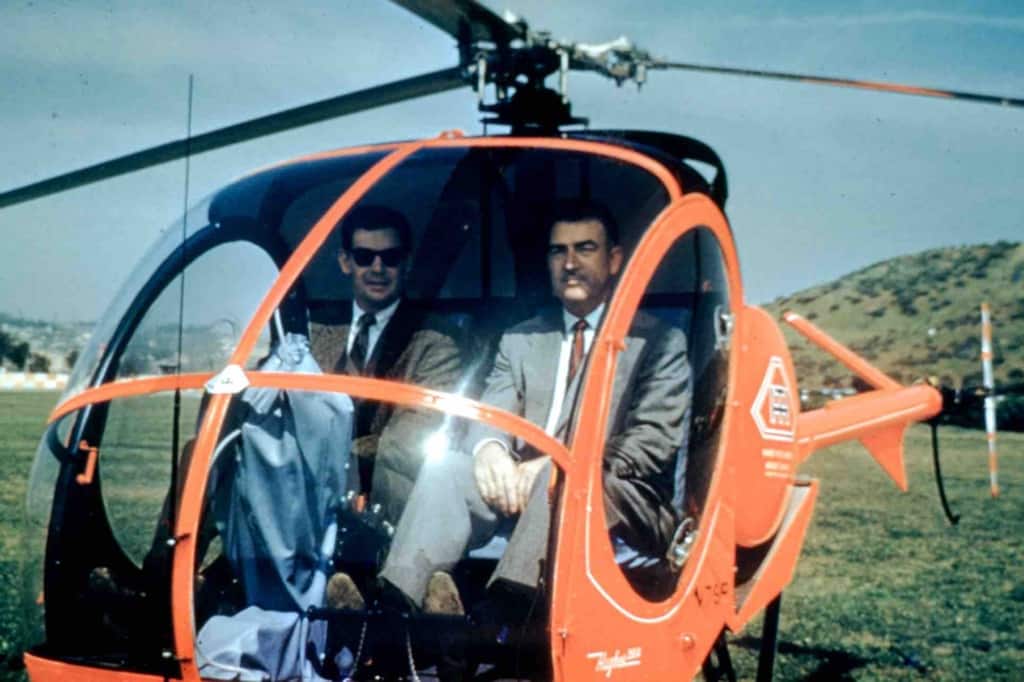

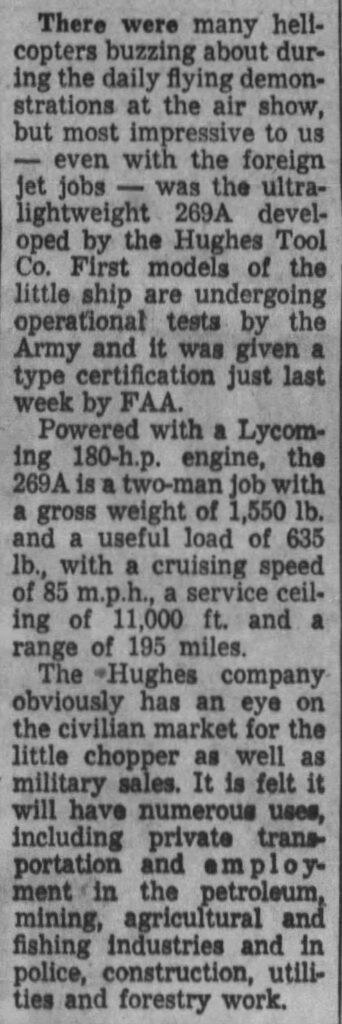

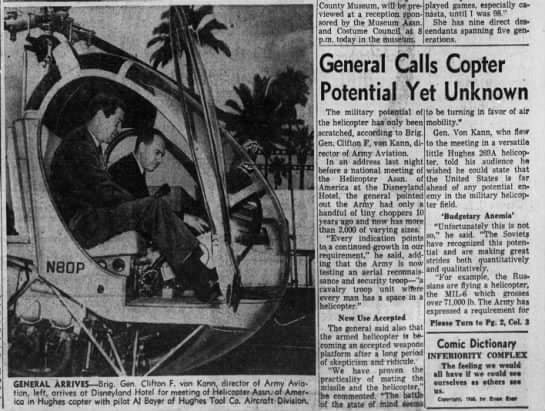

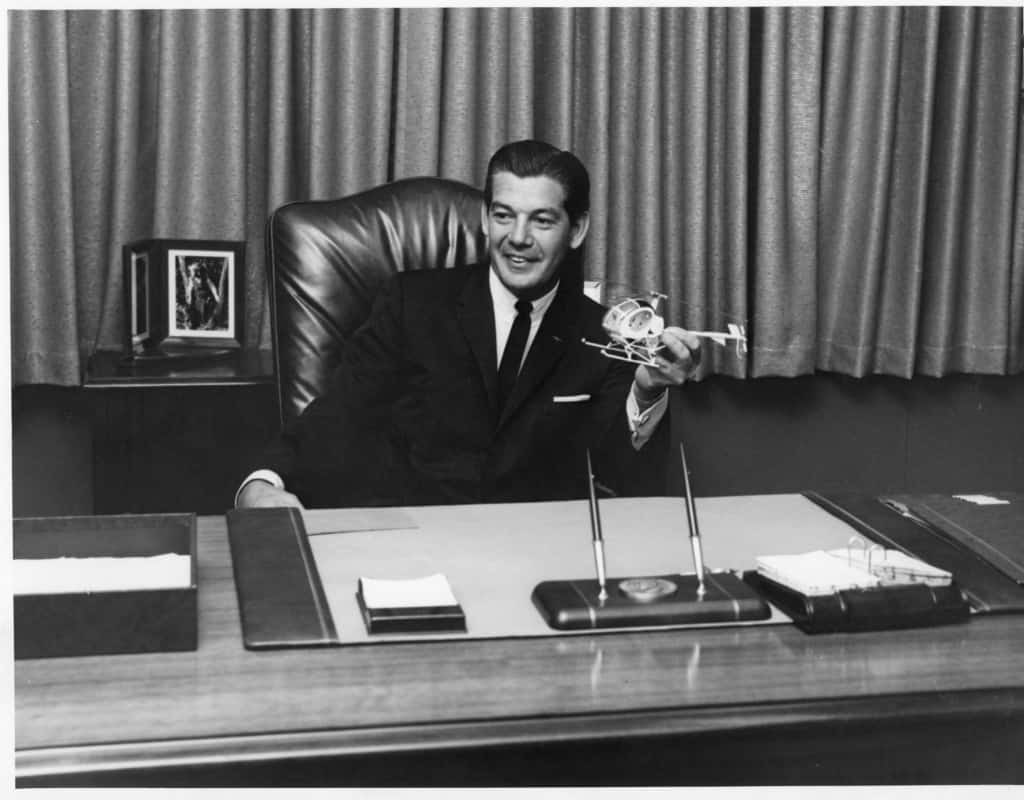

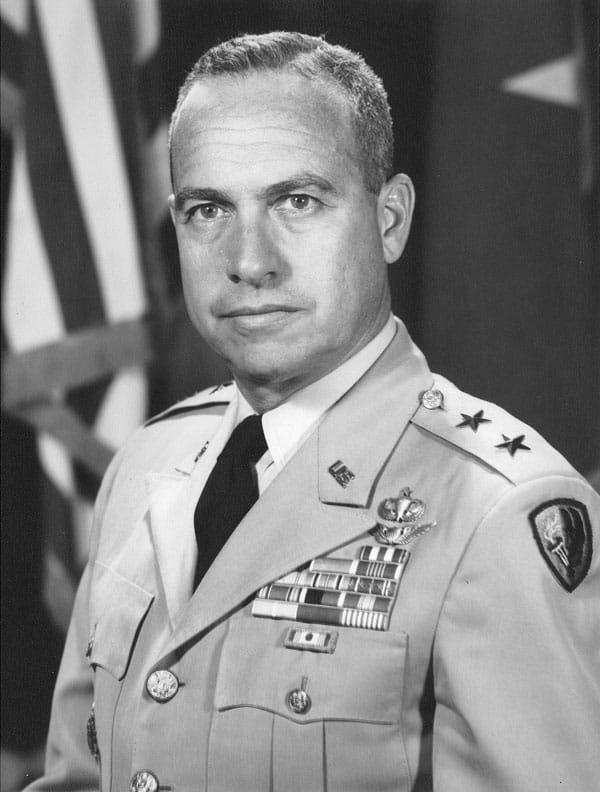

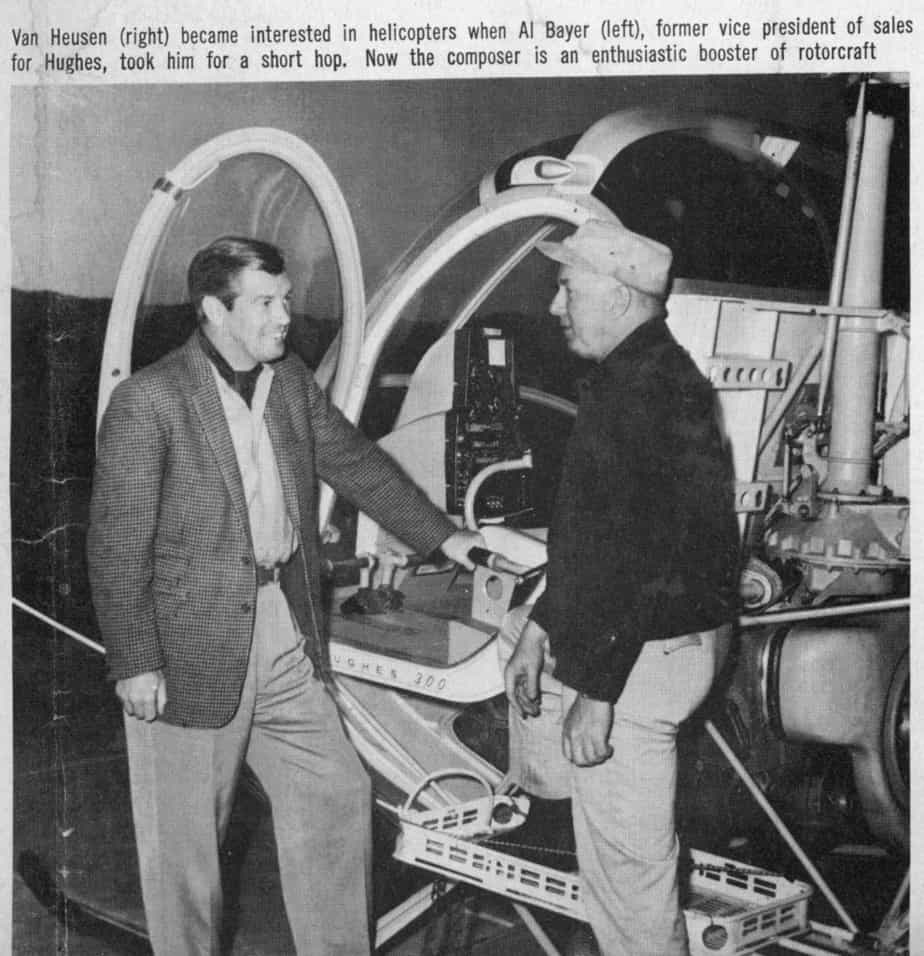

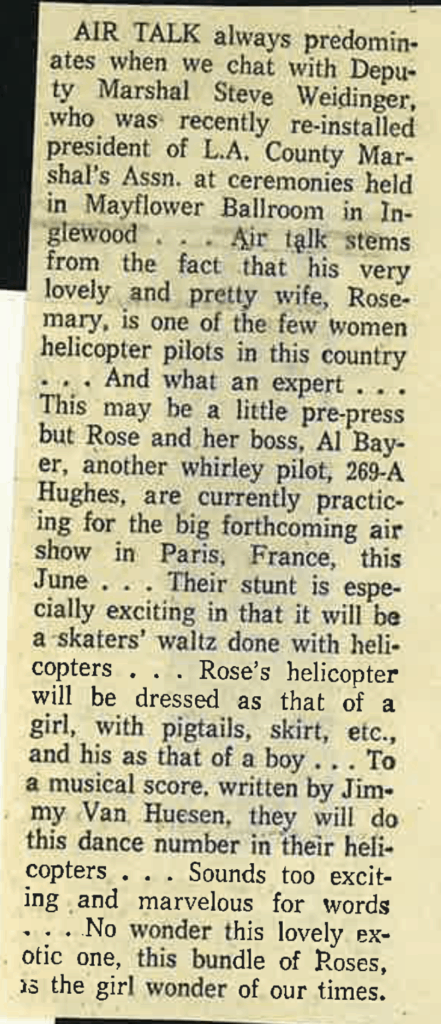

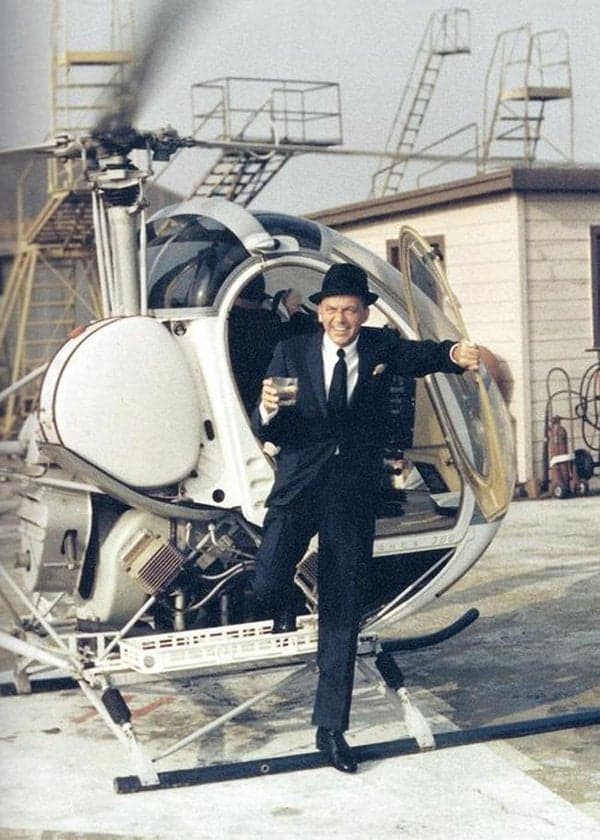

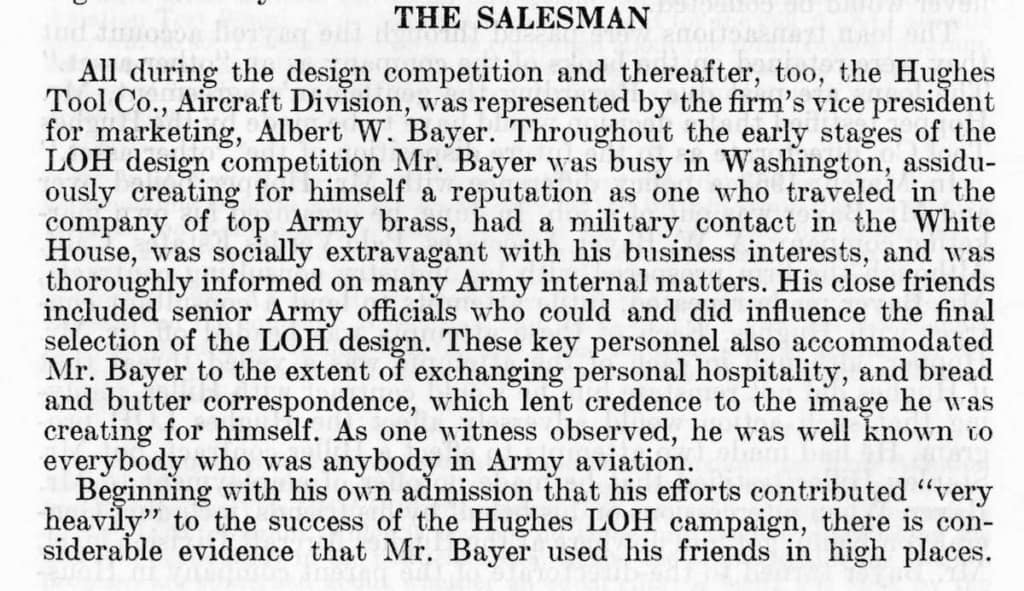

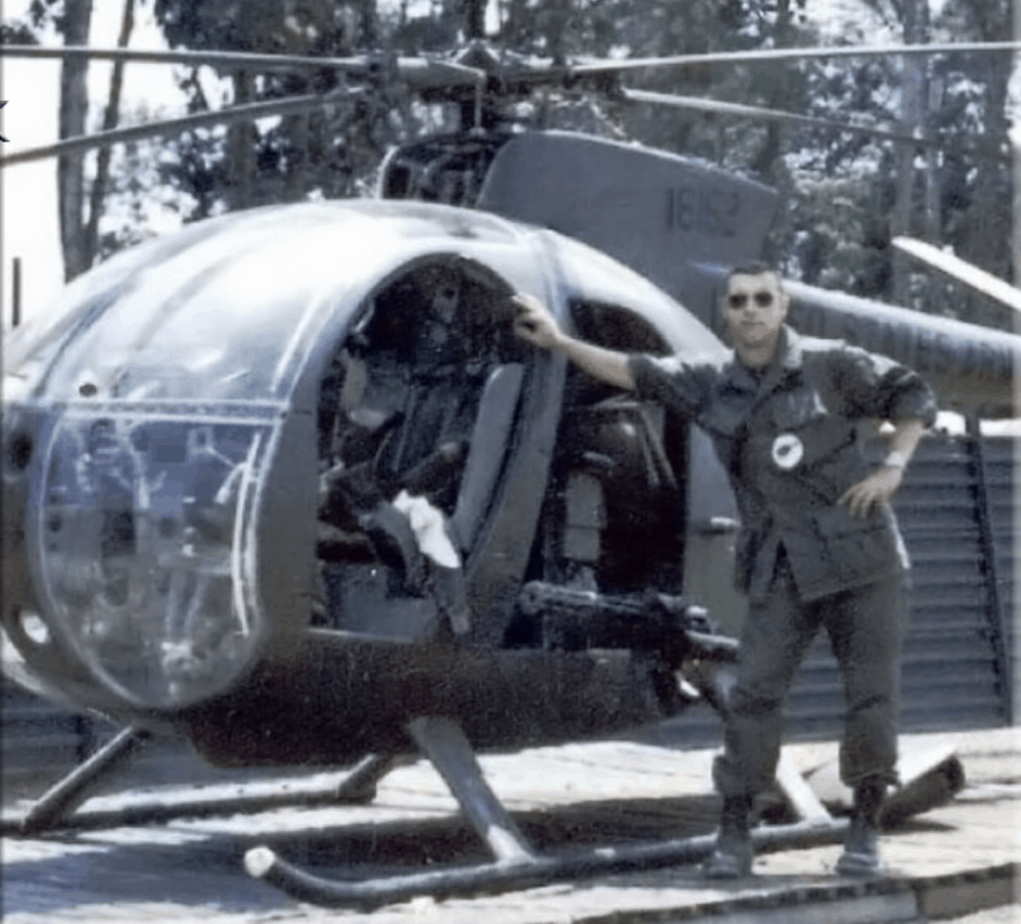

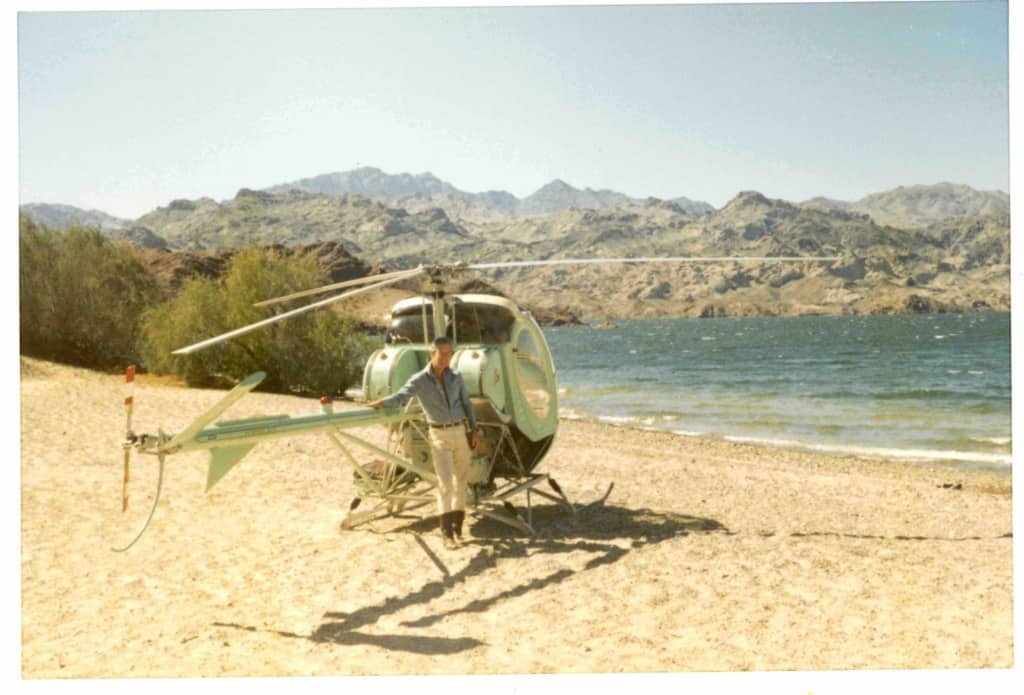

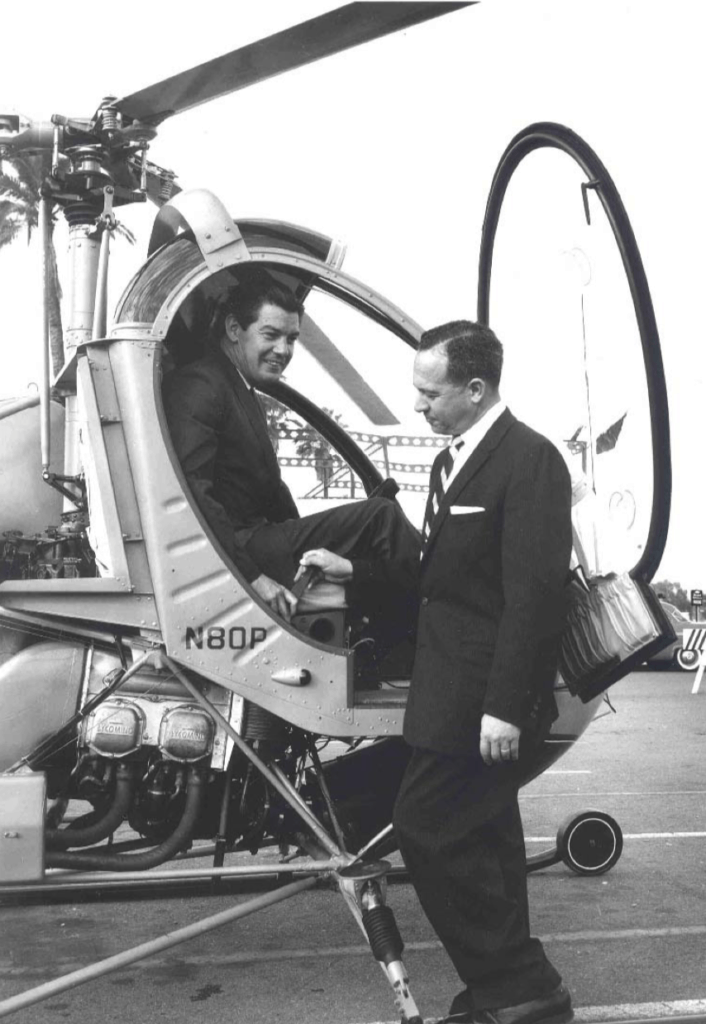

On the one hand, this is the history of my father’s career in helicopter development– an accounting and tribute to someone close to me. On the other hand, this is a fundamental story of helicopter development, the Southern California aerospace industry and the military-industrial sector of the 1950s and early 1960s. Prior to Al Bayer’s decision to personally demonstrate the Hughes 269A in April of 1959, the idea that a small and sprightly helicopter could be useful and practical was held mostly by eccentric inventors and test pilots. The owners of companies and much of the military saw such efforts as homespun, hobby-shop efforts in which they would only marginally invest. By the end of that year, Al Bayer had won the hearts and minds of some in army aviation, paving the way for a revolution in helicopters and military strategy. Here is his framed photo of himself flying the 269A at the onset of this conversion in April 1959.

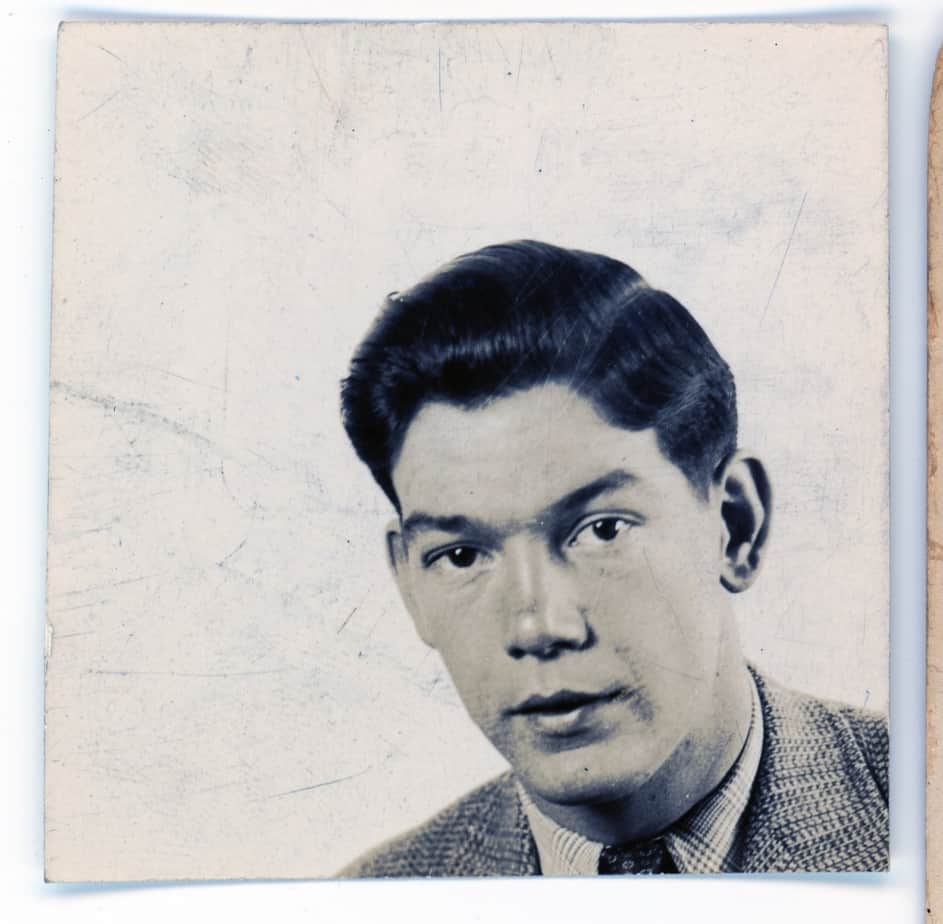

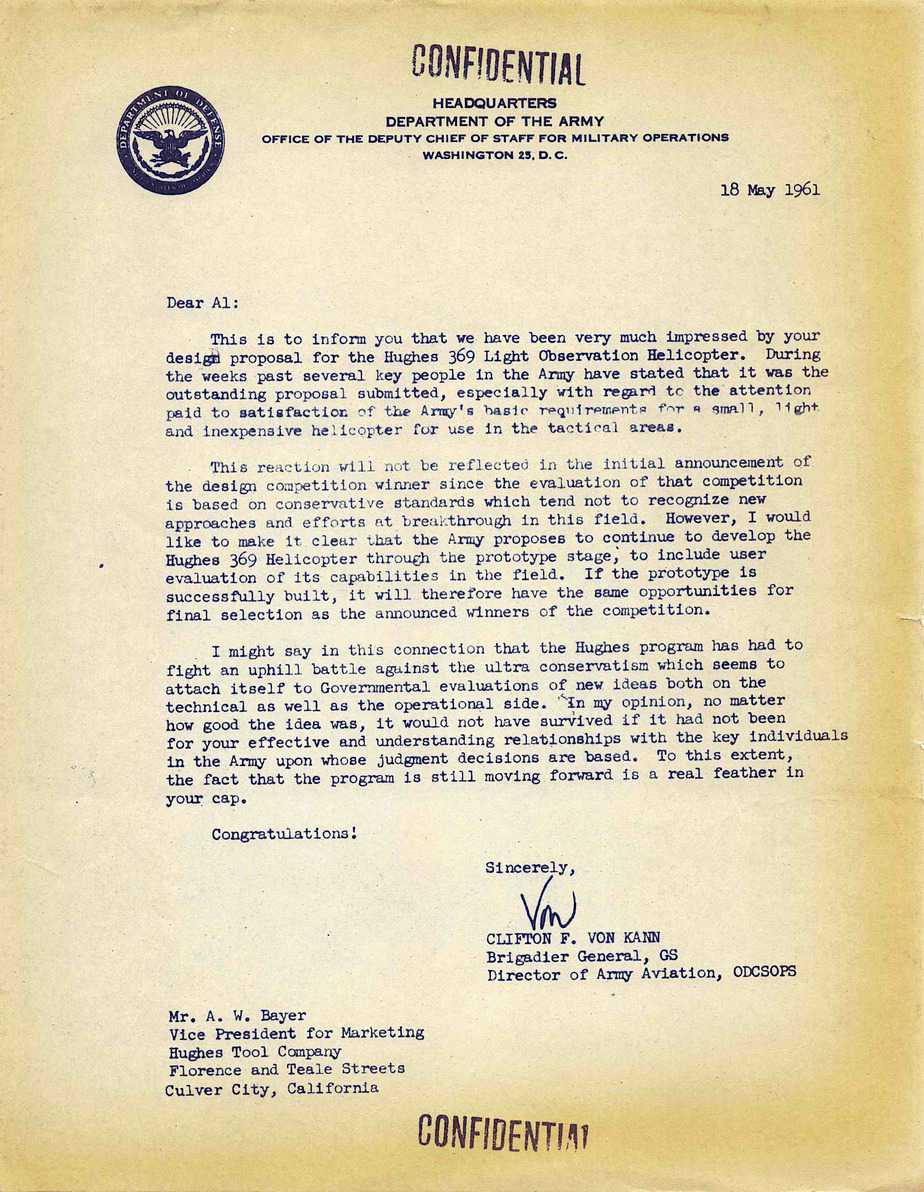

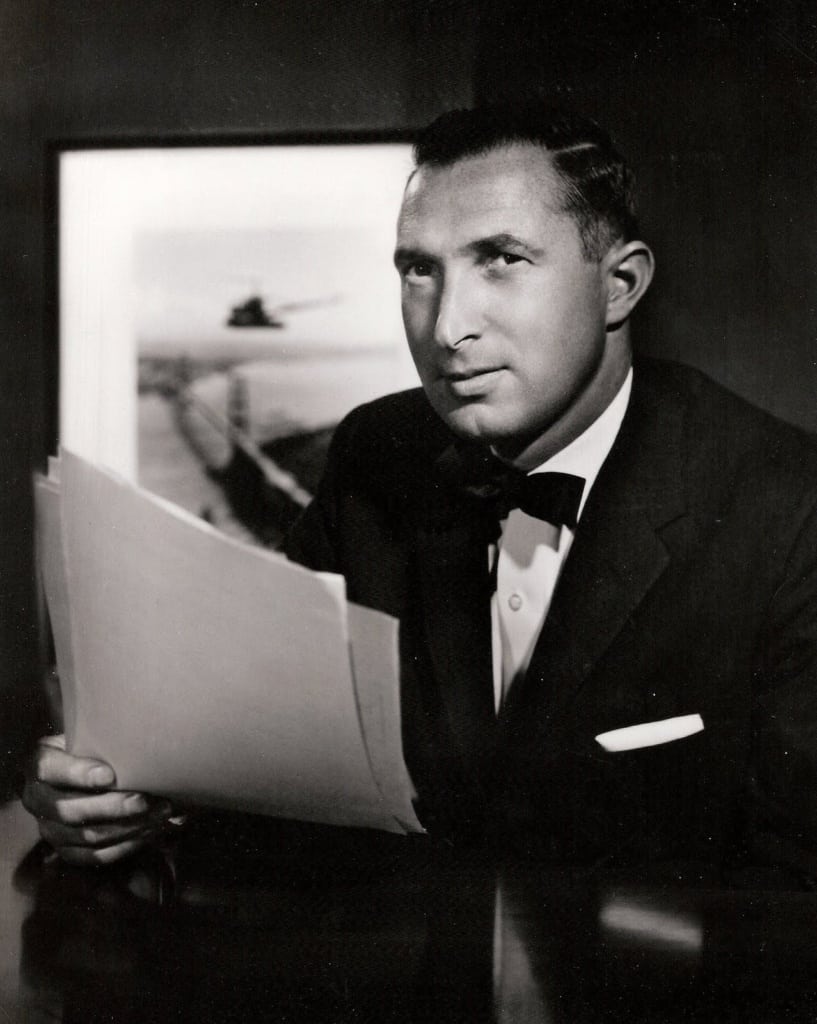

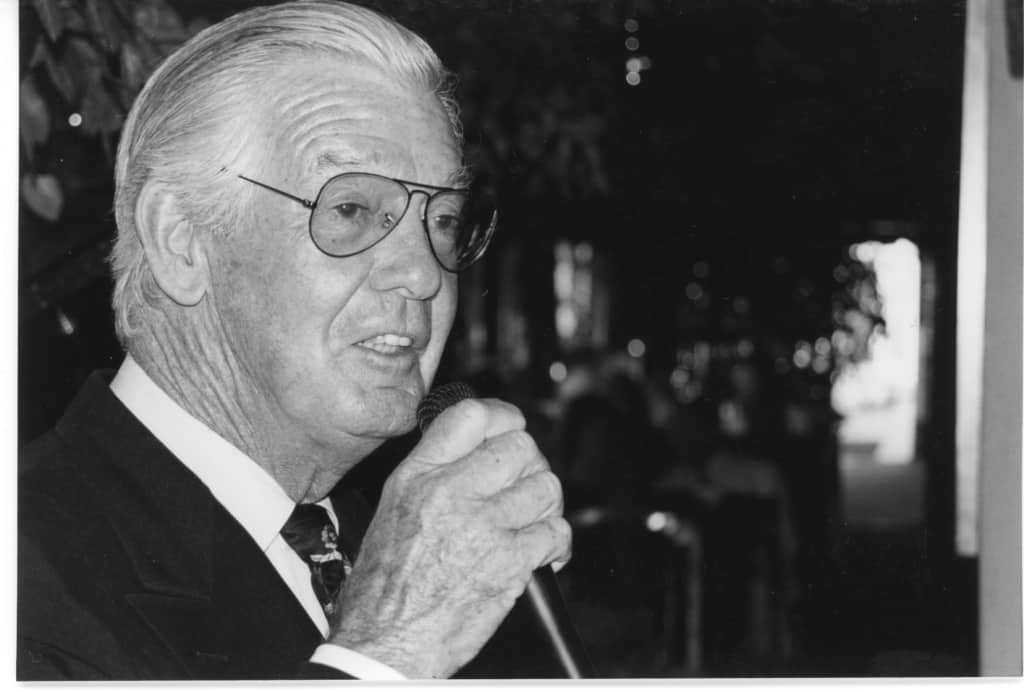

My father was one of the most innovative, creative and controversial aircraft salesmen of California’s aerospace industry during the 1960s. In this book you will find the account of his central role in transitioning the helicopter from cargo truck or troop carrier to dashing sports car and rotary fighter craft. Allied with engineers and Army progressives, he was the driving force that got the ball rolling in creation of what would ultimately be called the “attack helicopter.” He paid an emotional price for this, a price so steep that while he left me files with all the details, he never fully told the story. Prior to this account, perspective and appreciation of his role have been lacking.

I encourage you to push print and store a pdf copy of this story. It will not contain the videos and documents. But, at least the outlines of this history will survive. To this day, the role of the test pilots and salesmen is little told as the wonderful old planes and helicopters shine in museums. When people in the future look back at the helicopter in the Vietnam War, it may help to have an account tied to the struggles of flesh and blood people.

A lot of aviation history is written as dates assigned to aircraft models and horse power numbers. In contrast, the history below illuminates spersonal, social and political struggles parallel to a story of technology. It may remind us that progress comes at the hands of real, sometimes flawed individuals whose efforts may be little noticed during their lifetime, may be distorted by enemies or may even be dismissed. And, sometimes, in their lifetime, their personality is so powerful that it obscures what they accomplished–perhaps a tangible step forward.

As I looked at my father’s papers and at the books that have been written about these events and as I remembered him as a person that I knew well, I realized that the climax to my father’s years in helicopter development proved so painful for him that, even years later, he could never fully tell that story–only allude to it in dinner-table anecdotes. The forward drive of his efforts never allowed him to adequately go back and reflect–even as he carefully filed documents away for me to someday find. To say this differently, on the one hand this a story of deception, risk and deflection. On the other hand, it is a story of intense focus and innovation.

Here is the tale of a smart and sometimes reckless young test pilot who pushed his way to the top, who succeeded by ignoring or out-maneuvering everyone who stood in his way and who, at the moment of success, found himself sidelined from the work he loved due to the very qualities and efforts that had brought success. While several of his friends, top brass, in Army Aviation came to crave a nimble helicopter, there was only one man in the industry who had carefully and over time positioned himself and the craft so that this vision became a reality–my dad, A.W. Bayer. While there are many museum–and, too often, aircraft museums, that present the past as a collection of curios and artifacts not unlike a circus sideshow, this is a story in which the amazing artifacts play out the ambition and work of characters.

Bayer’s firing came at the hands of a company that, when he joined it in the mid-’50s– was widely regarded as inept by both the government and by the aerospace industry. After he left, in large part due to his push for the Hughes 269A and then the 369/LOH/500, Hughes Helicopter went on to mammoth success–converting Hughes into a major and respected aerospace firm. After his firing, he was targeted, blamed, victimized and pushed out of helicopter development. Still, to key men in Army Aviation during the 1960s, Bayer became an unsung hero. This assisted him in his career after he left helicopter development. And, yet, his personal loss was dramatic, coloring his life and my life for decades.

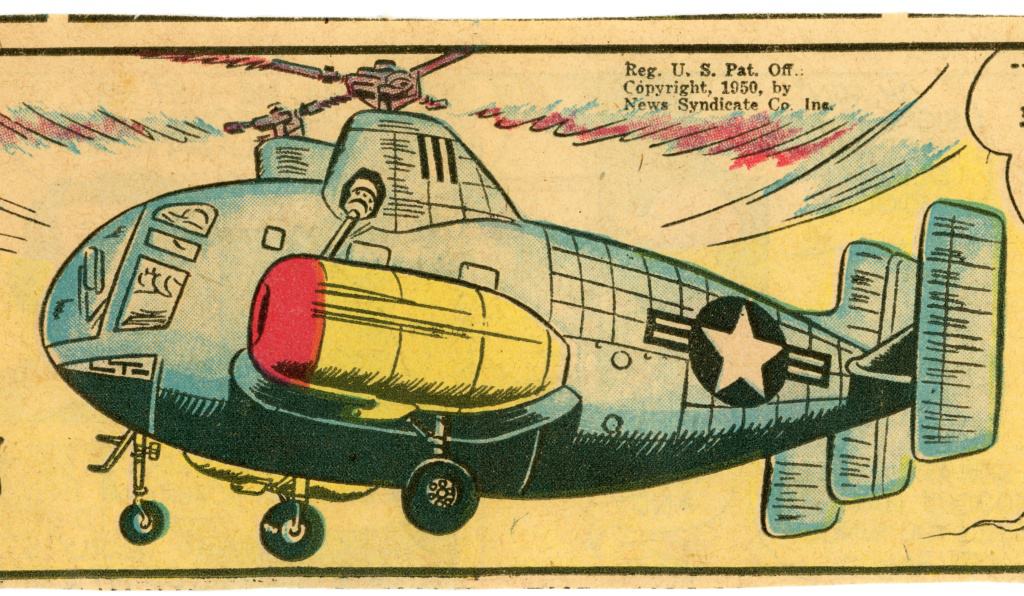

More concretely, this is a tale of how geeky bravado and a California aircraft building climate full of possibility helped move American technology from boyish, Popular Mechanics dreams born in the 1930s into a sophisticated, military/industrial empire that redefined warfare and global power. This transition reflects a faith in science and technology as a pathway to positivity and individuality that, in today’s America, seems to have faded. At the same time, this is a story about dreams and about “cool”–about the “Hollywood” science fiction thrills of a futuristic wonderland that propelled boys inside of men. And, at its core, this is a story of pants-in-the-seat test-pilot risk taking.

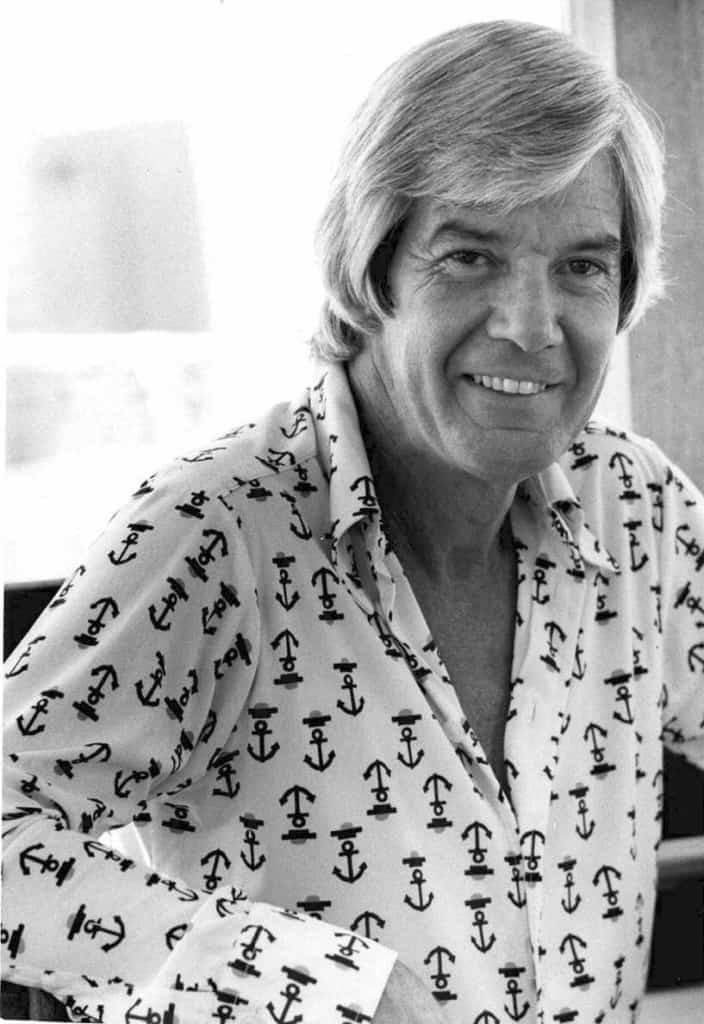

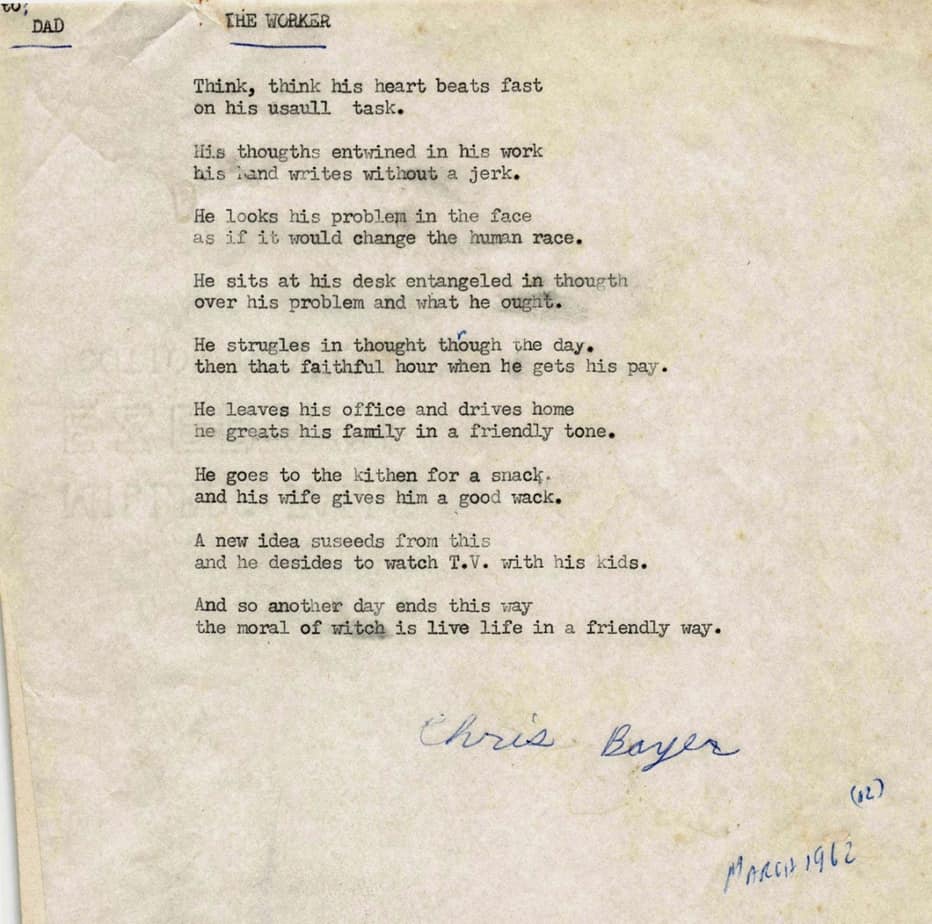

My father loved to tell stories–stories that entertained, stories that also deflected from the details of his past. He expressed wonder at where he had been and at what he had done. Yet, no one in the family knew exactly what he was referring to–what he had done. “Unbelievable”, he liked to say. He titled it “Unbelievable” yet only wrote a couple pages. In it, after he arrived at the critical events of 1963, he drifted off into name dropping, listing important people he had met–much as he frequently did during his later years.

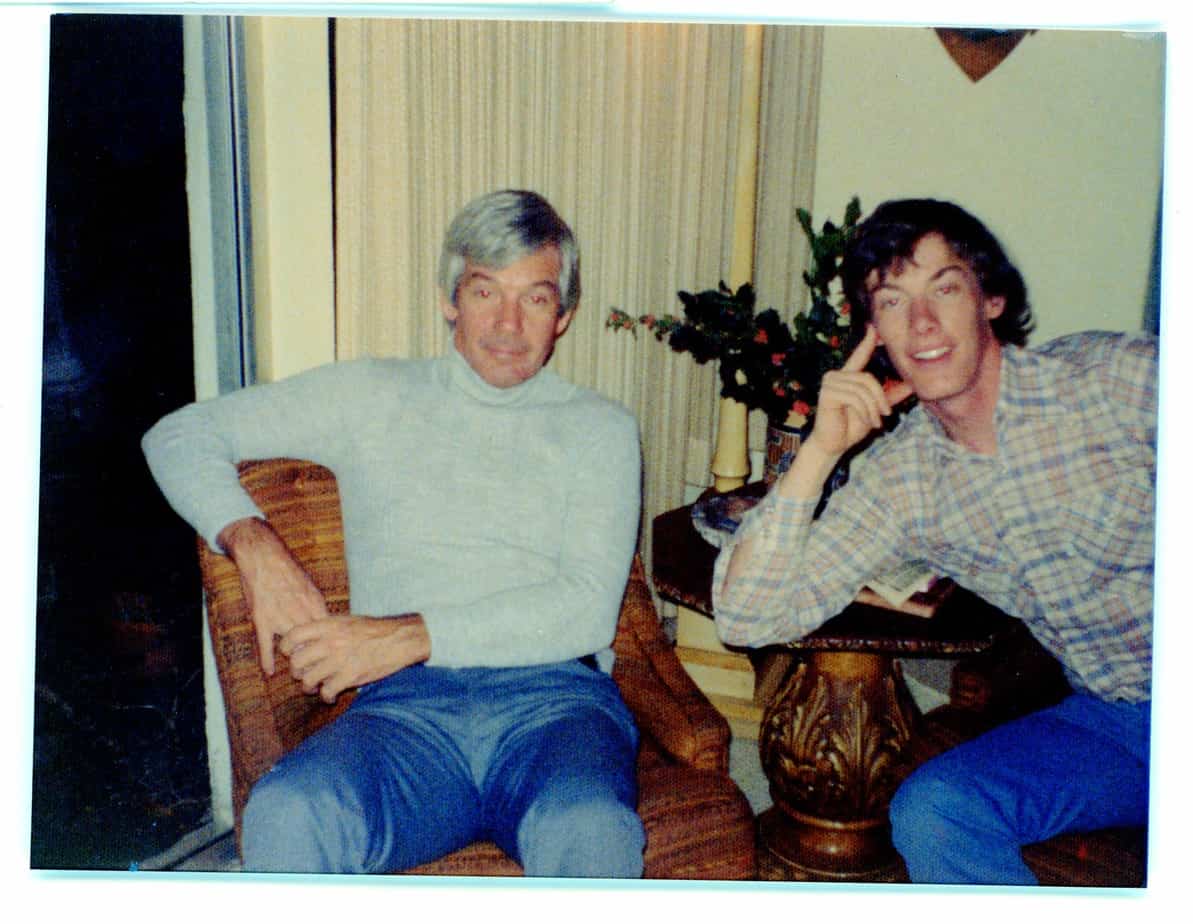

I believe my father always knew that this history mattered and was remarkable. However, I know that he did not understand why it mattered or why it was remarkable–he was too close to it, too tied to the hopes and heartbreak. Looking at these events, I’ve come to better understand he triumph and failure that often reflected his personality and the compromises he made along the way. Though young, I was there. I grew up with the themes in this story. Part of my ability to write this history derives from my long-standing awareness of contradictions in my father’s personality–some of which I share–and a resulting awareness of his goals and their complex context.

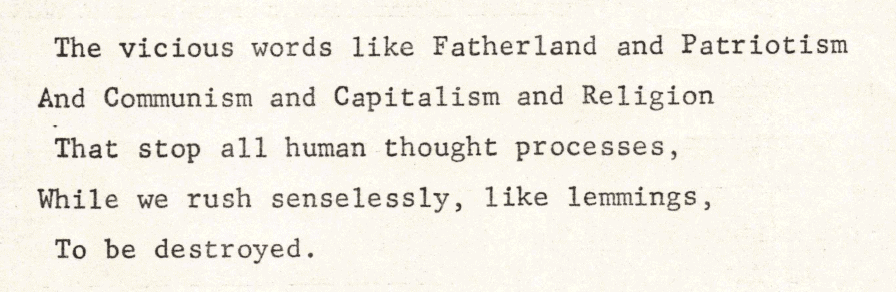

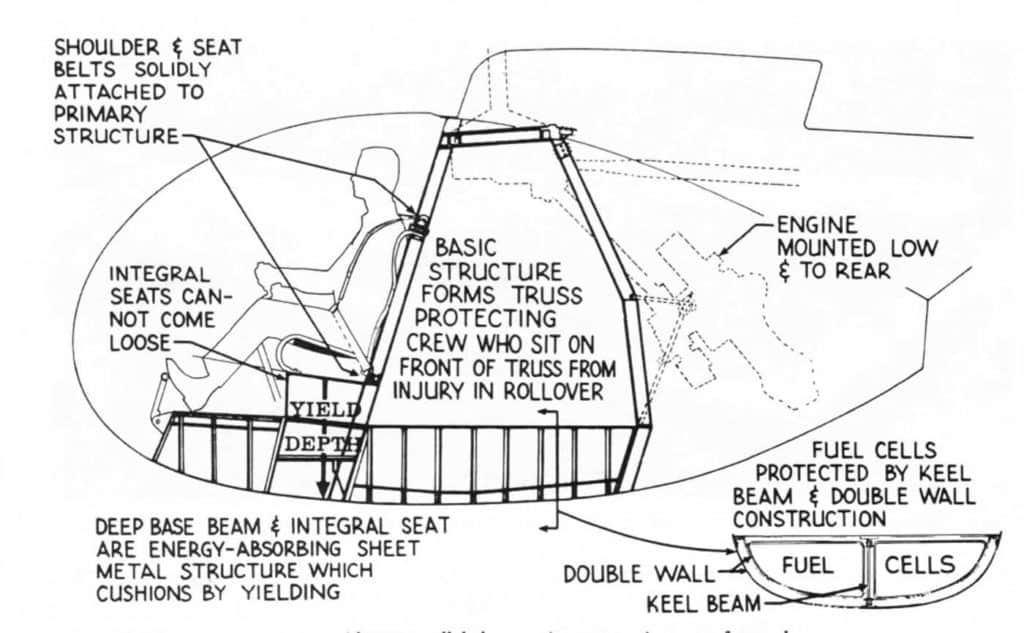

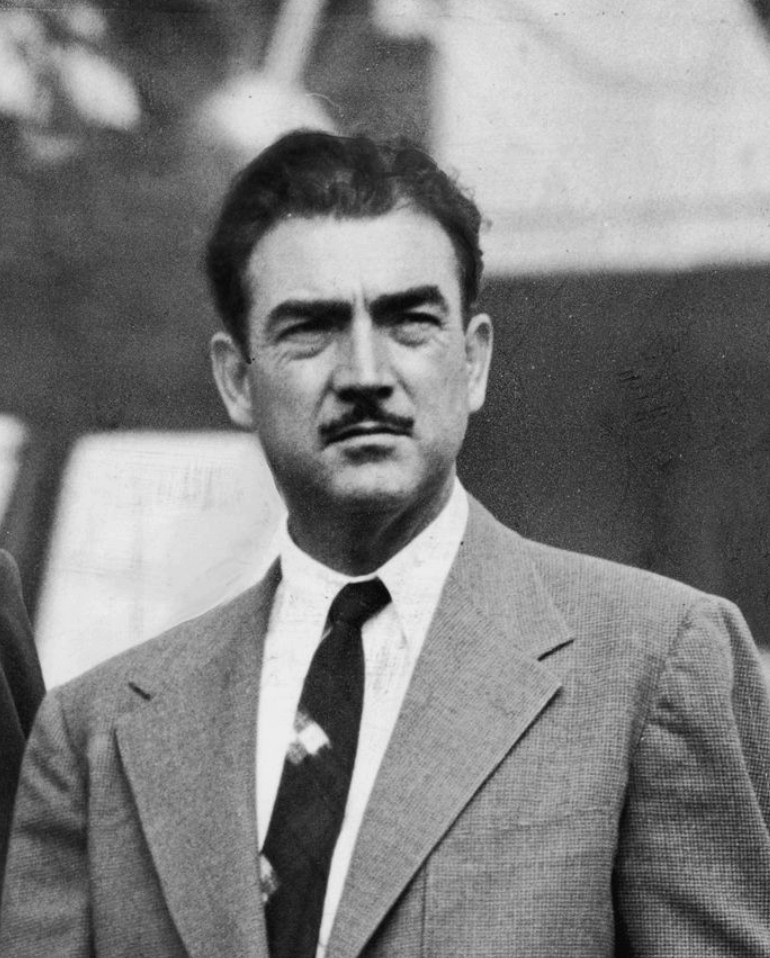

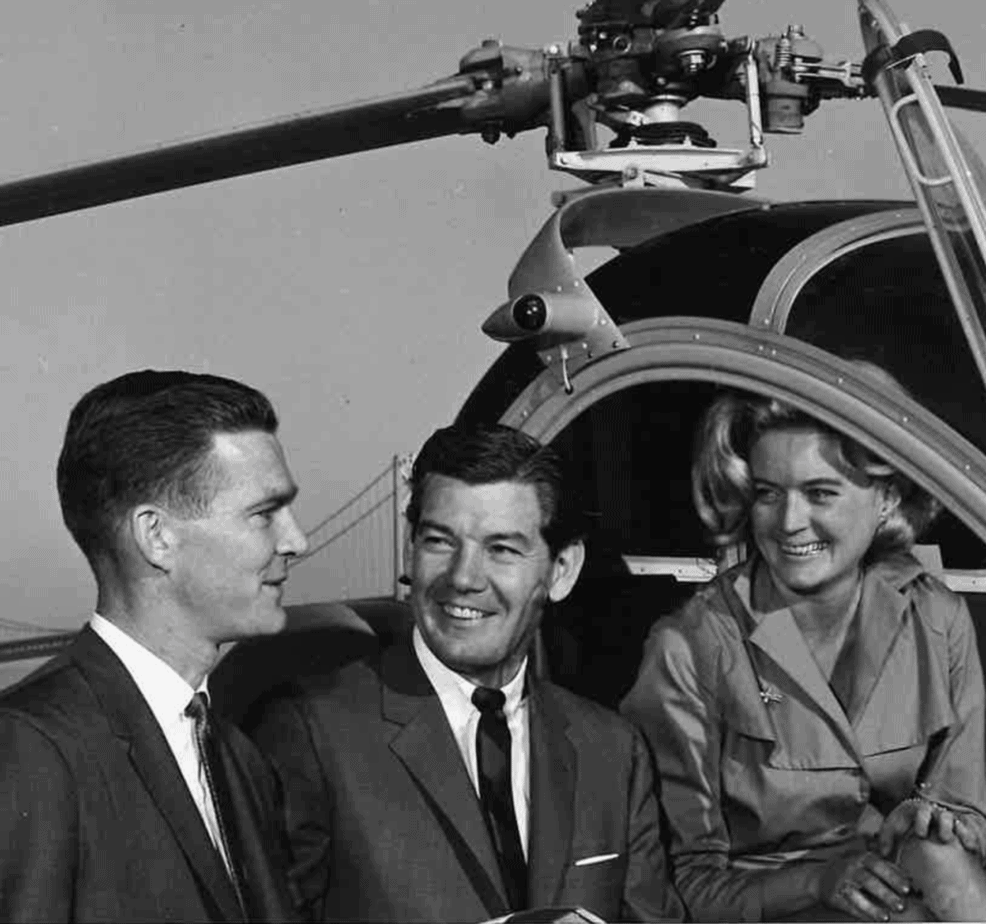

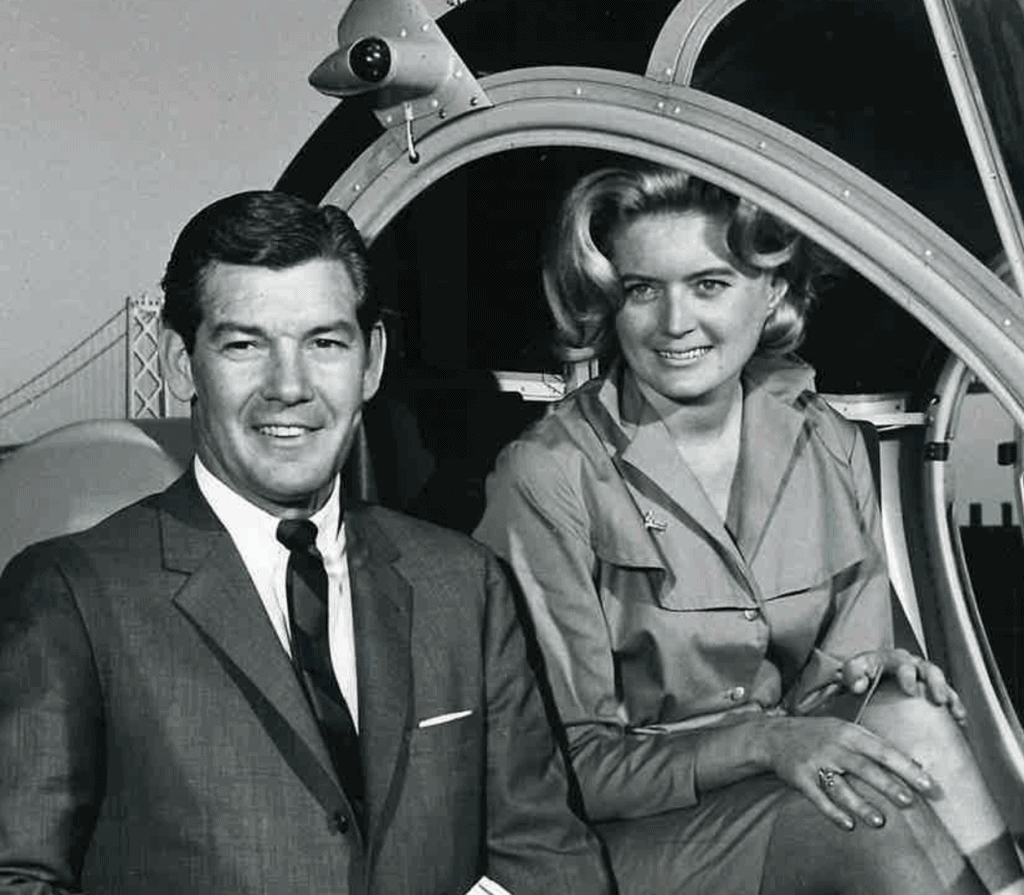

This history is more than a list of airplanes and corporations. Though this history begins with half-baked machinery, it traces a shift during the 1950s as America became a military-industrial superpower consumed by fear of communism and yet ever more confident in its superior technology. My father worked at the heart of a shift from the mass production of WW2 to the refinement of sleek, deft and “cool” machinery and “systems”. Most stunningly, he and engineers who were his friends envisioned the small, deft attack helicopter decades before it was called an “attack helicopter.” Beyond these trends, this is a history of three people– Bayer, Jovanovich and Von Kann–plus one more: Weidinger. Each played a central role in a small but intense drama that created the defining weapon of the Vietnam War and changed the helicopter forever.

If my father would have trusted anyone to tell this story and document the things he might have said or could not say, it would have been me. However, he did not do that during his lifetime. He gave me hints. Mostly, he pushed the past aside and, until the end, kept pushing forward. At the end, what stood out was a willpower that outstripped his physical ability to survive. “It’s amazing that I survived,” he often said, toward the end of his life. Now I understand why he said that.

Having contacted museums and, too often, received no reply, at this writing I remain concerned that this story and the papers I have will remain lost to history. American aviation history tends to be dominated by a shallow obsession with bigness or with metal, model numbers and dates. Yet, behind the documents, this is first and foremost a history of ideas, concepts, branding and sales–my father’s aviation world, a world he imagined and acted upon.

I have scanned several collections of Memos and Correspondence from this story. These are of value both for the information they contain and for the information they do not contain–as contemporaneous files, a collection of everything Bayer had in hand. I’d like this story and all these documents–here and inserted in this story– to survive.

- GE Memos and Correspondence, 1945

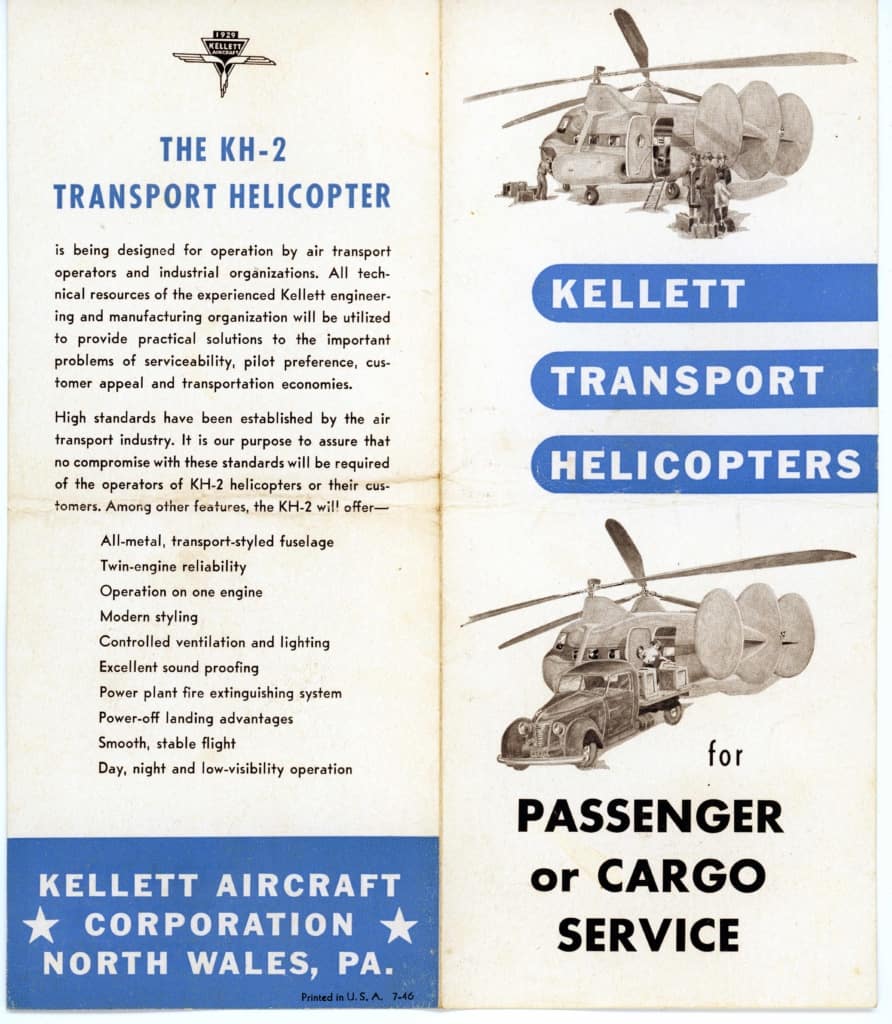

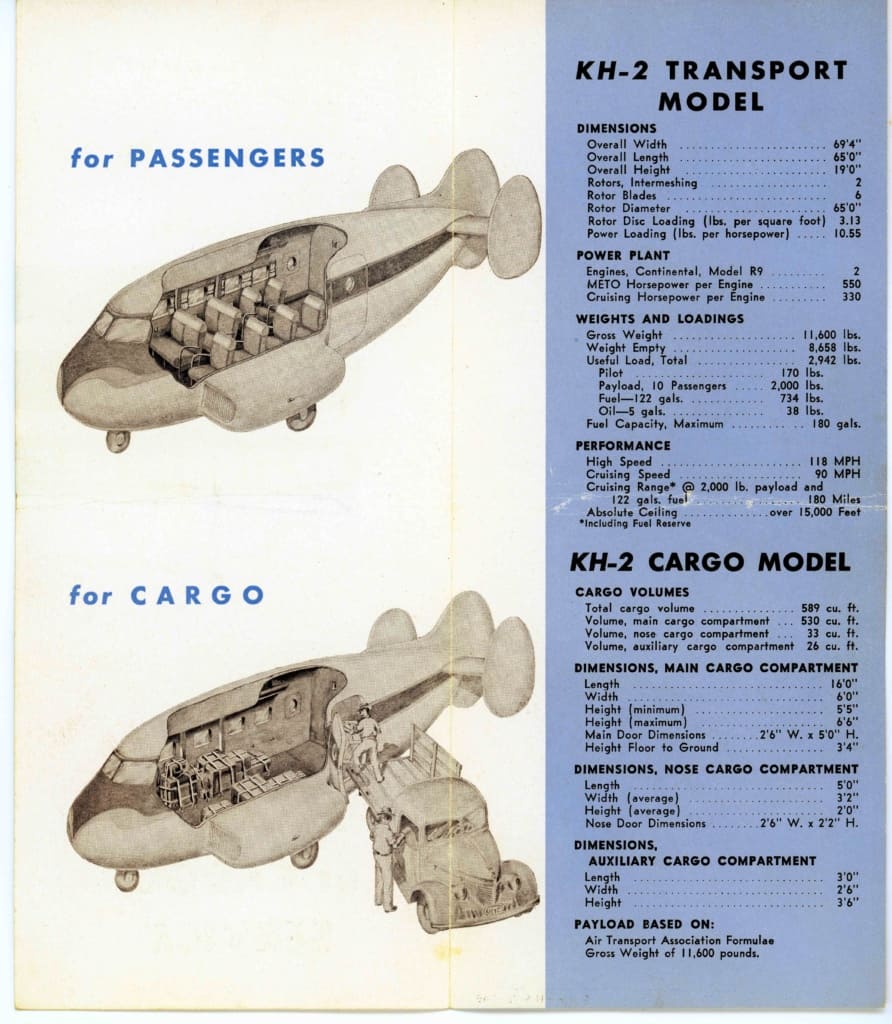

- Kellett Memos and Correspondence, 1947-1948

- Kellett XR-10 Flight Test Reports, 1947-1948

- Kellett XR-8A Flight Operating Instructions.

- Design Aspects of the Kellett XR-8A Helicopter

Inevitably, as Al Bayer’s son, I am part of this story. At times, I step into the narrative with comment and personal information. Mostly, I refer to my father as “Bayer”, my mother as “Rita” and myself as “Christopher.” I hope that my father would be happy to finally have his story on record. I imagine arguing with him that some things need to be included even when they might appear unflattering.

Below, I’ve included more than you may wish to read–reading only the narrative might be a good idea for most people. I’ve included documents and links because portions of this story have been written wrongly so many times. And, they make for a more three dimensional story. This page can be a lot for your computer to handle. I think most computers can do it. Still, don’t rapid scroll. Let the page load for a few minutes. The chapters in the Contents box below can be jumped to by clicking on them. The endnotes can be accessed at the end of the story by clicking the + sign there.

If you have information that would improve this account, please email me with any documents or suggestions at nevadamusic.com@me.com

Feel free to donate with PayPal button below. It helps.

Thanks! CW

LETTERS, PHOTOS, DOCUMENTS – an introduction, how this got started

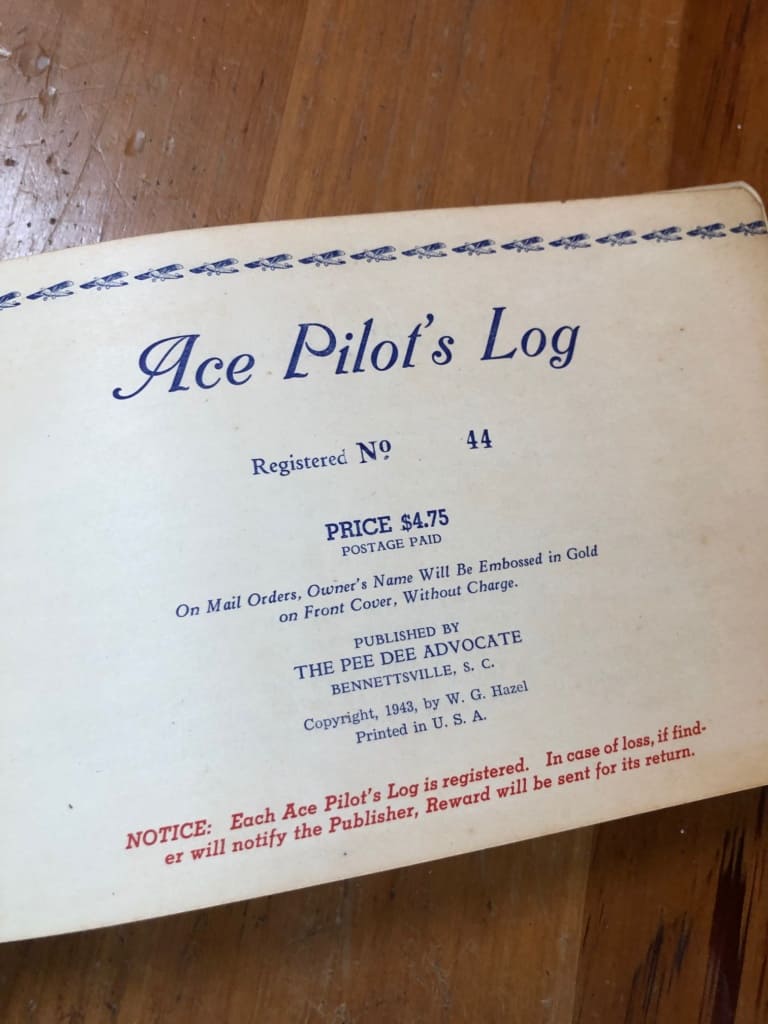

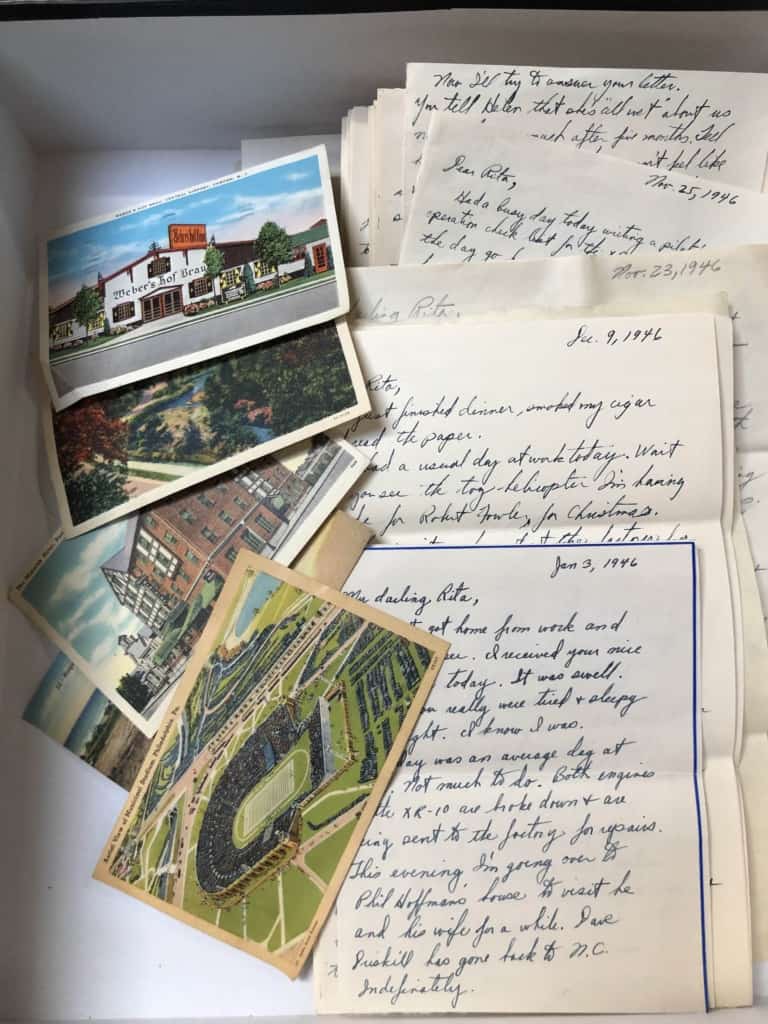

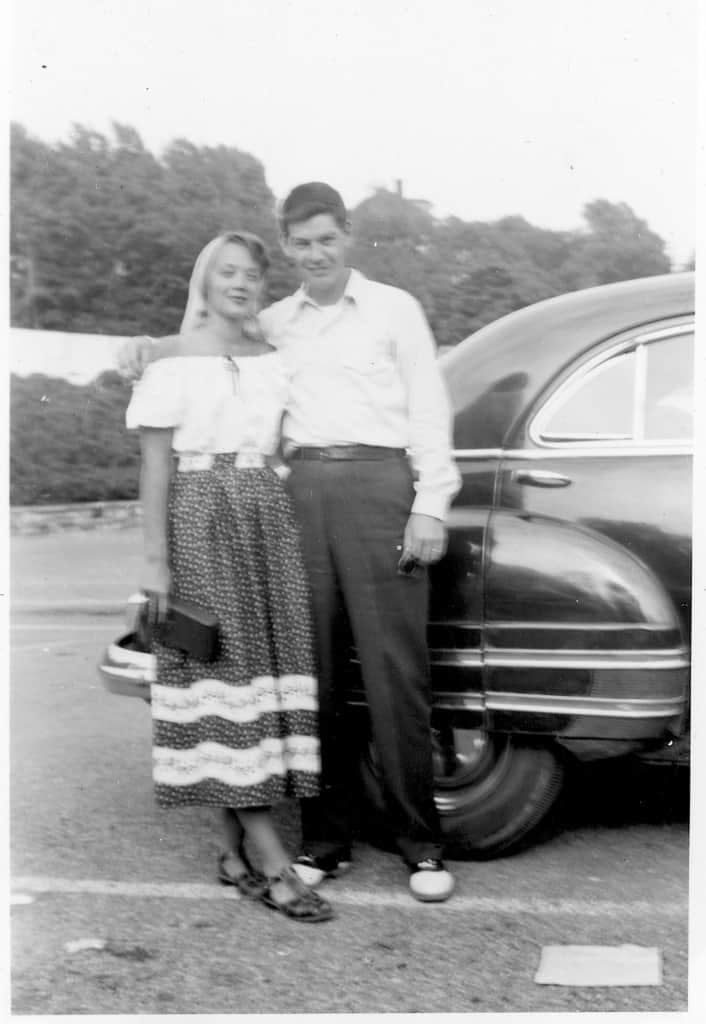

I finally opened the trunk of love letters and postcards. They lay in two batches–one from my father to my mother, the other from my mother to my father. The letters had not been read since 1947. They had long remained in their envelopes with three cent stamps bearing the likeness of Thomas Jefferson. Albert Bayer (1925-2002) wrote love letters to Rita Cusack (1924-2015) from September of 1946 into June of 1947, during their courtship as they planned their marriage and he worked in Pennsylvania while she remained in Schenectady, New York.

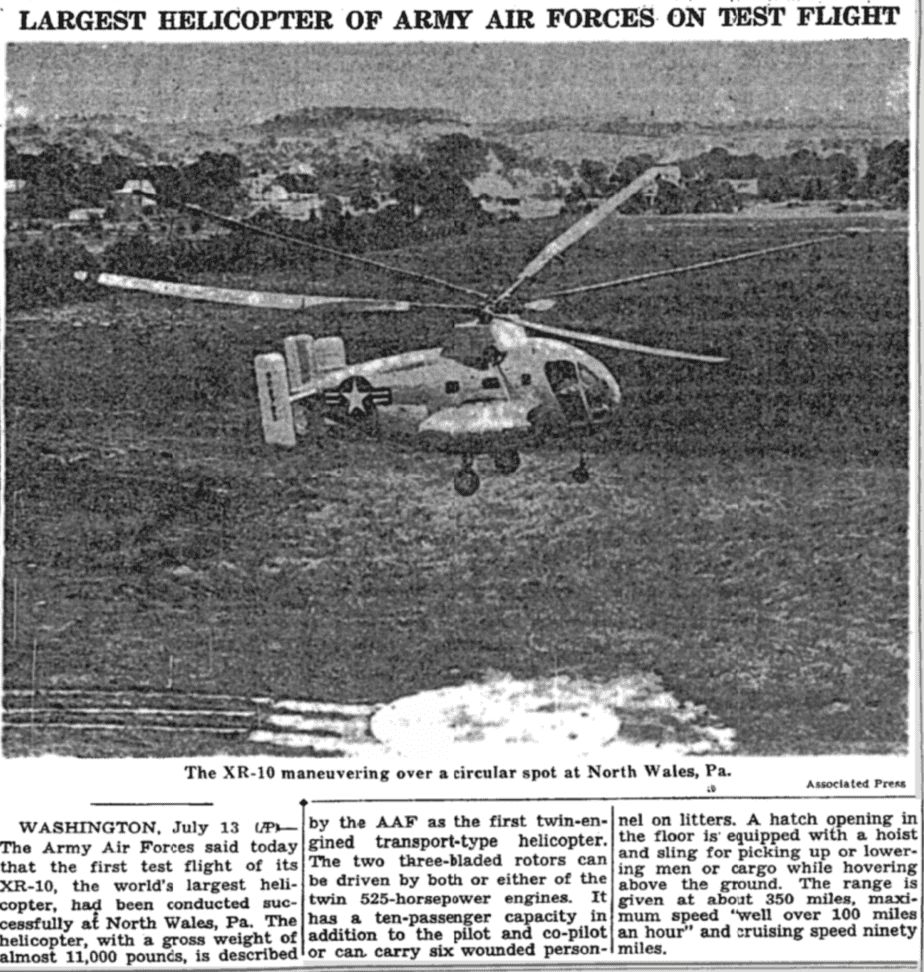

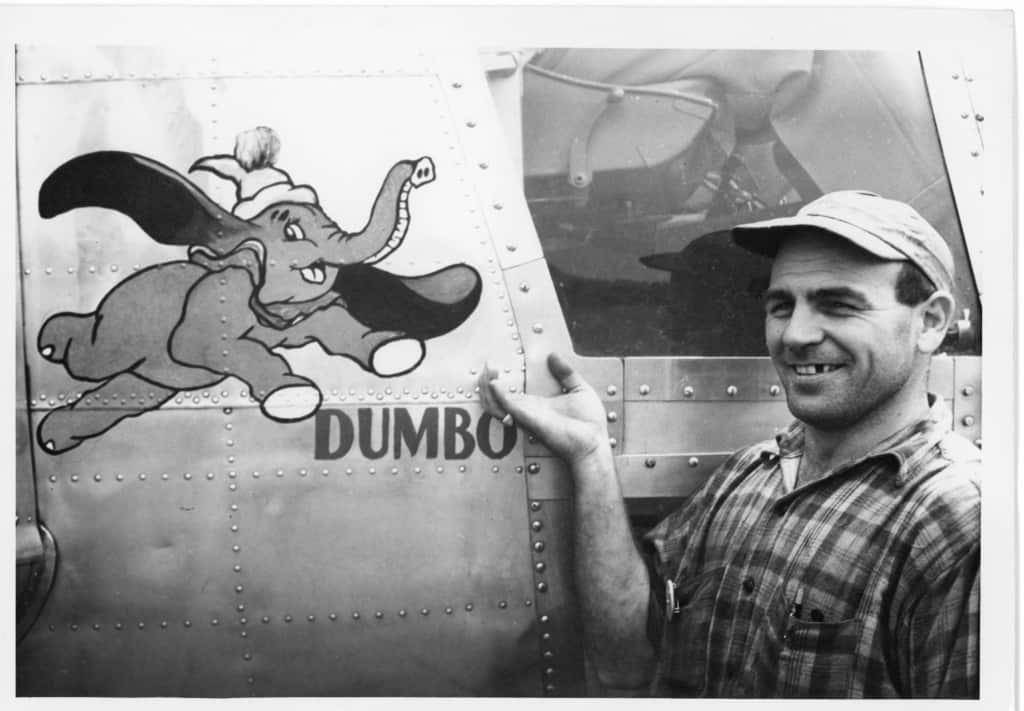

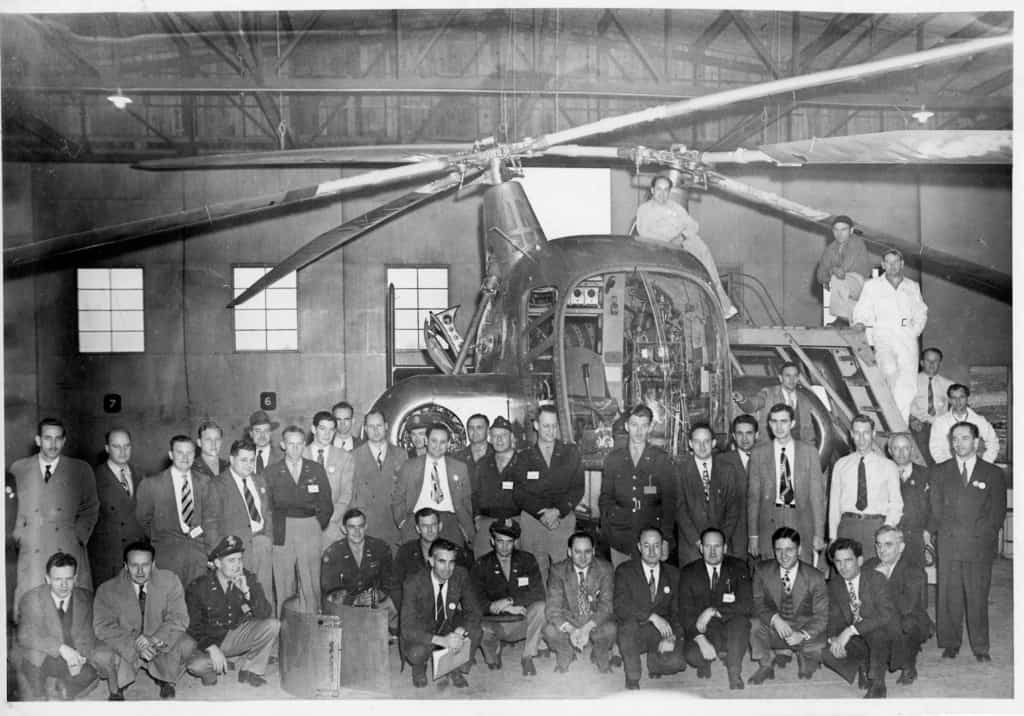

Reading those letters, I came upon my father’s personal account from the late 1940s of his work as “Engineering Test Pilot” on Kellett Aircraft’s XR-10, the world’s largest helicopter at the time. I began to see a bigger story, one that I had heard pieces of during my father’s lifetime. Old men would whisper sometimes. Brushing them aside, my father would laugh and say, “I am a character!” I had the letters. I had much more–photos and documents from his filing cabinet. I began to see the details I had missed while he was alive–the central role he had played during an important period in helicopter development. I saw that I had stacks of documents that may be singular copies from that era and that I could create a narrative that needed to be written. I saw the dramatic story that he would never fully tell. And I began to understand why he could not tell that story.

My grandmother, Emma, saved my parents’ 1940’s love letters. When she died, my mother, Rita, put the letters in a battered and dusty dresser drawer out in our garage. When my mother died, I put the letters in an old trunk that I stored in the back room. They long remained tempting artifacts. I was reluctant to pry into my parents’ courtship. Then, having retired, one day I wanted to use the old trunk for camping. I saw this as an excuse to pull out the folded writings and read some of the lines. Written during their courtship, many of my father’s letters expressed his love.

Sweetheart I love you, I love you, I love you, honest, with all my heart. Go to sleep now, sweet dreams. “I wish that I could hide inside this letter, etc.” I’m almost doing that. We’ll get there almost the same time. Darling I love you Honey, I love you. Don’t forget that big long kiss. (Can I help it if I love you so much? Huh? Can I?) All my love, Al. 1Letter Al to Rita, date missing from this letter.

And then I found what he wrote to my mother about being a test pilot.

A DEATH DIAGNOSIS – background to taking great risk

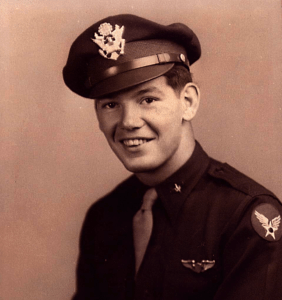

Born in 1925, with black hair and buckteeth, the youngest of four children, Al Bayer grew up in a working class German/Irish family in Schenectady, New York.

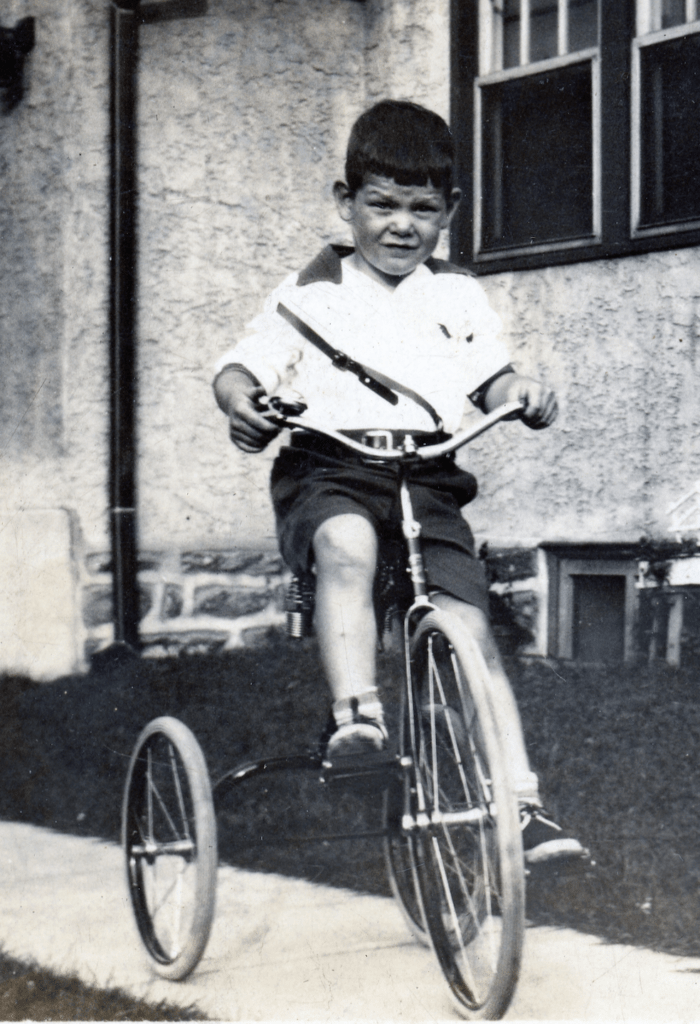

His grandfather, Henry Bayer, emigrated from Germany as a teenager. He and his relatives comprised part of a German band that enlisted en masse during May of 1861, becoming a Union regimental band for the 2nd New Jersey Infantry as the nation entered the Civil War. Henry went on to work for Edison and obtain several patents. Henry’s son, Harry Bayer, worked as a school janitor and loved to garden, fish and hunt. During the ’20s, Harry and Alice Bayer performed comedy songs in the local vaudeville-movie house. They entertained as the crew changed the silent-movie reels. Harry sported a glass eye, a tramp hat and an oversized cigar. AW Bayer grew up knowing all the old songs and how to charm an audience. During 1929, in Philadelphia, Bayer took his first airplane flight with his Aunt Anna at the controls. That year, he was more interested in his new tricycle.

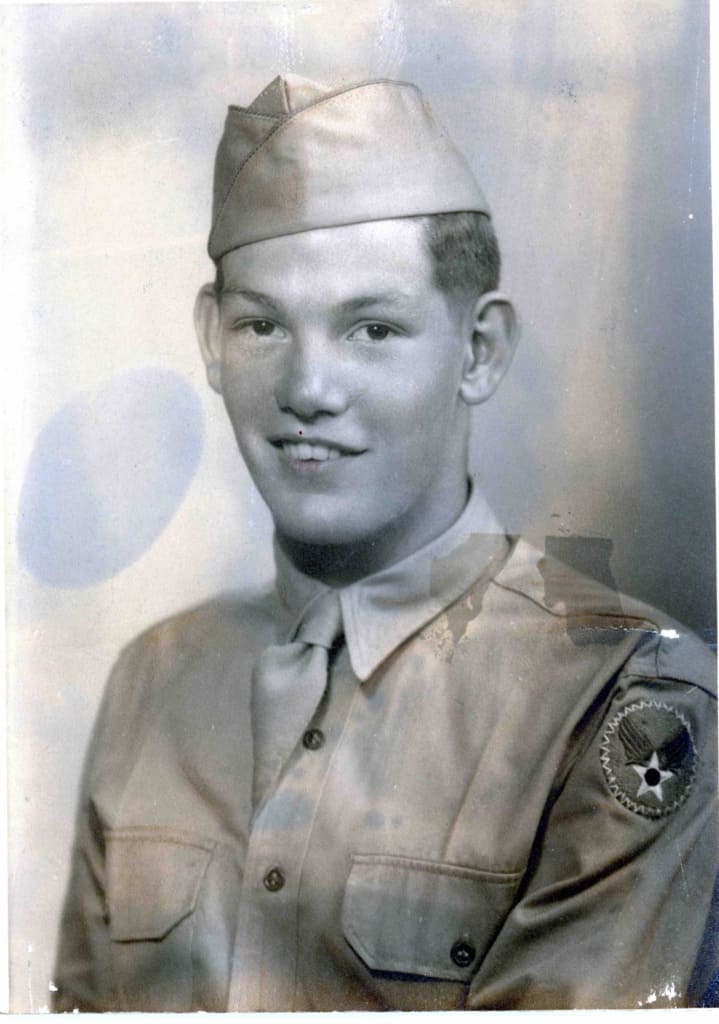

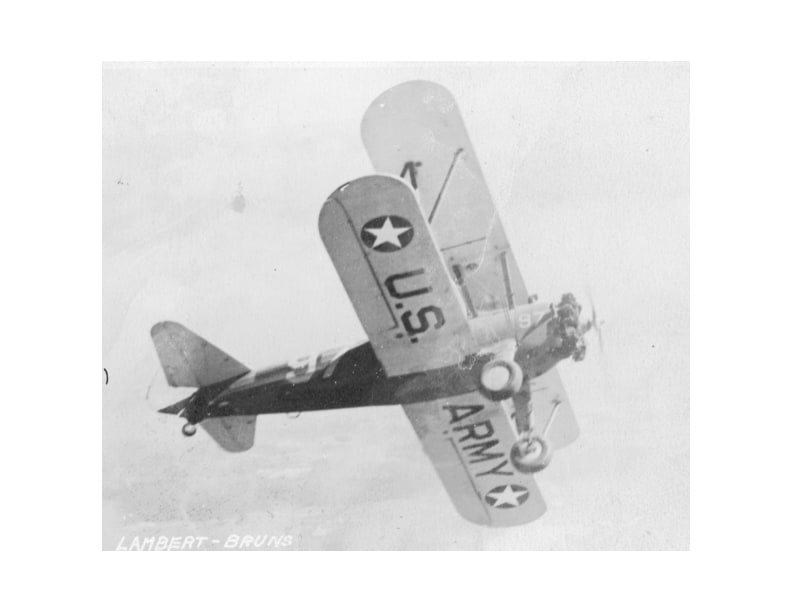

In January of 1943, Bayer graduated from Mont Pleasant High School in Schenectady, with honors in the college preparatory electronics course. He seems to have had a talent for mathematics. He began studying engineering at Union College. After a year, he left to attend the Air Force program at Catawba College for six months. In 1943, he joined the Army Air Corps. Bayer transferred thru a succession of training camps. In February 1944, Bayer began military flight lessons in the Stearman PT-17 and, in April graduated as an Air Cadet. He began studying to become a bomber instructor. However, he never completed that effort.

In September of 1944, military doctors diagnosed Bayer with a lymphosarcoma located in the cervical glands under his right ear. During November, he underwent surgery and radiation treatment. 2Diagnosis, Bayer papers. Not expecting that Bayer had long to live, the military ended his active flying during September of 1944. His medical discharge was completed in January of 1945. 3I have his army papers. Date is based on letter, Bayer to Tozer, March 18, 1952. He would remain devoted to Army Aviation into his 40s.

Bayer later told me that, at this point in his life, believing he had little time left to live, he set about to live life to the fullest–wild and free, taking whatever chances came along. He credited his success in life to the reckless daring in which he then engaged–becoming a test pilot–under the belief that he would soon die. Eventually, his decision to take risks would be somewhat tempered by hard events and the fact that he did not perish from the disease. By that time, he had learned some lessons about how to fly and yet continued to take risks. He later wrote:

I believe that fearlessness as a result of lymphosarcoma and test flying plus a large dose of good luck resulted in my becoming a successful V.P. of Hughes at age 35.

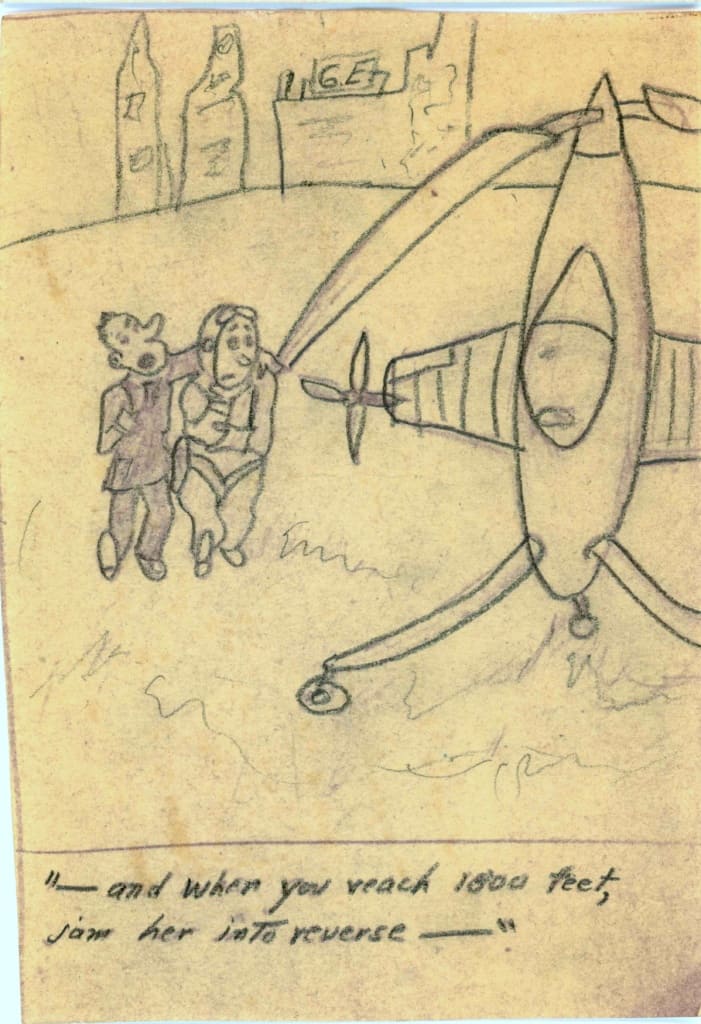

JAM HER INTO REVERSE – the General Electric convertiplane

In February of 1945, Bayer applied for employment at General Electric in Schenectady, New York. The company had begun to build a hanger at the old Dutch hamlet site of Alplaus. World War II continued to rage. Both the military and industry were caught up in the development of new technology–a momentum that would continue after the war, inspired often by technology captured from the Germans. During the war, there was big money in developing weapons. After the war, many of those wartime industries sought to keep the funds coming in.

In the wake of the war, GE’s aviation projects focused mostly on radar and jet engines. Seemingly as a sideline, GE initially had some interest in rotary aviation as a vehicle that might be propelled by small jet engines. The company seems to have been pitched this idea by the Russian born Igor Bensen (1917 – 2000), a mechanical engineer. They hired him for two related projects–the XGEH-2 Heliplane Project and the Hermes Project. 5GE Memos and Correspondence, Bensen to Prince, 1945 These began in November of 1944 with a proposal by Bensen proposal for “data collection”, as if to merely lay the basis for something more substantial in the future. It was probably all that Bensen could get GE to fund. 6Report Bensen to Prince, Aug. 23 1945 GE Memos and Correspondence

By this time, Allied bombing had effectively ended German helicopter development and the Allies were beginning to capture German military helicopters. Young men fascinated during the 1930s by stories of rotary aircraft–particularly the popular lore of the autogyro–now saw military funding as a means to realize these dreams of the everyman, personal aircraft. Where the military only saw the helicopter as a cargo, troop carrier and rescue craft, the futuristic visions of these young men went well beyond that staid idea to dreams of dashing about the sky. The military tended to remain somewhat ambivalent about the helicopter as a whole. Some in the military believed that the military had not adequately embraced the potential of the helicopter during the war, particularly its use to rescue sailors.

The initial goal for Bensen lay in a small rotary aircraft with jet engines mounted on the tips of the rotor blades. Bensen’s memos at GE refer to “automatic gyro-rotor controls”, suggesting that one of his lay in a smoother transition of a gyroplane from vertical to horizontal flight–accomplished with sophisticated mechanical gearing. 7Report Bensen to Prince, Aug. 23 1945 GE Correspondence GE contracted with Kellett Aircraft in Pennsylvania to supply an old autogyro and parts for the project that would be assembled in Schenectady.

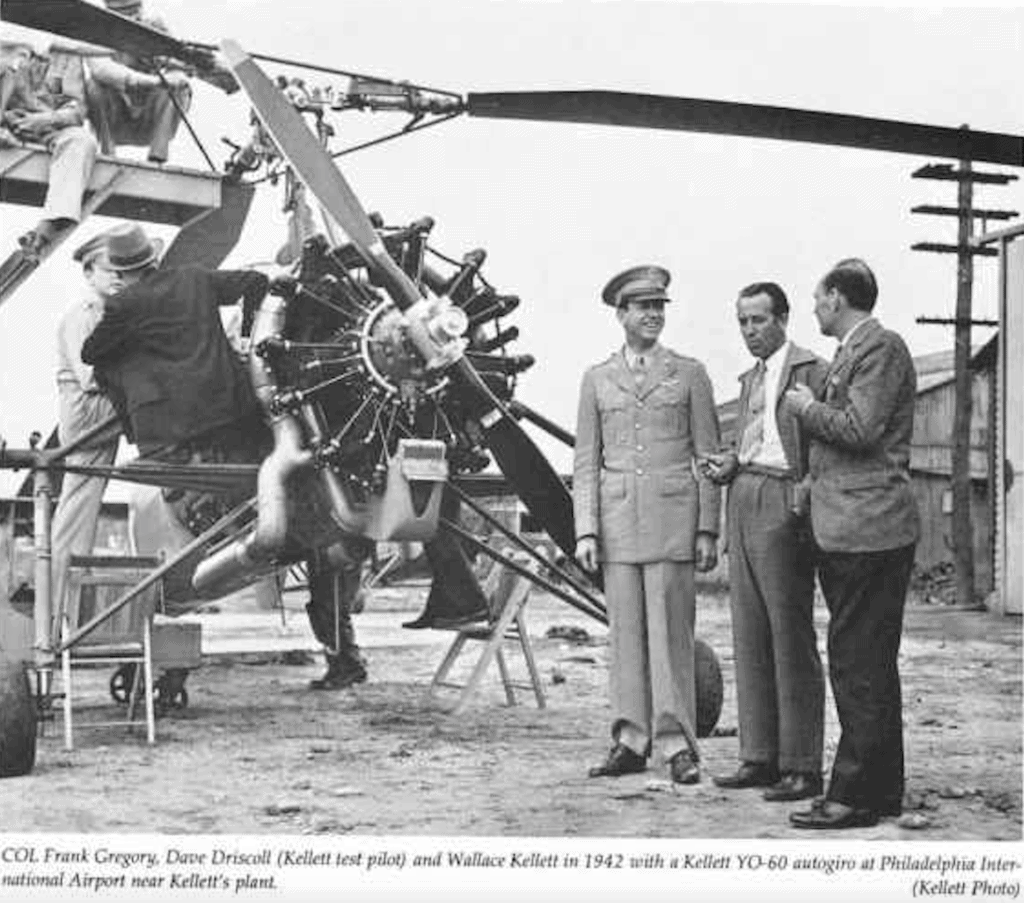

In 1929, the brothers W. Wallace Kellett and Rod Kellett formed the Kellett Autogiro Corporation and began manufacturing Autogiros, under license from Pitcairn-Cierva Autogiro Company in Upper Darby, Pennsylvania, and later near the Philadelphia Municipal Airport. 8https://vtol.org/who-we-are/our-history/philadelphia-region-history Wallace had flown a fighter plane for the French Air Force during WWI. During the 1930s, Kellett Aircraft was a primary builder of rotary aircraft–autogyros.

Though the company entered WWII with some financial problems, Wallace Kellett (December 20, 1891 – July 22, 1951) had funds from other sources and possessed a passion for rotary aviation. He had built some of the best autogyros of the 1930s. 9https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/W._Wallace_Kellett By 1943, the Kellett brothers had seen Sikorsky obtain a helicopter contract with the military. Still, the military was expressing little confidence in the autogyro design. In rotary aircraft, it long tended to favor big and sturdy over small an maneuverable. The Kelletts shifted from autogyros to work on a helicopter–the XR-8A. The Kellett Autogiro Corporation changed its name in 1943 to Kellett Aircraft Corporation. 10Kellett’s Eggbeaters: The XR-8A and XR-10, Roger Douglas Connor, Curator, Vertical Flight Collection, Smithsonian Institution, National Air and Space Museum, Washington, D.C.

During WW2, German and Japanese military interest in rotary aircraft went in other directions. In 1939, after obtaining a Kellett KD-1A autogyro, designed in 1934, the Japanese built 240 of them for use during WW2. 11http://www.aviastar.org/helicopters_eng/kellett_kd-1.php The Germans were working on a small maneuverable helicopter. The Bensen/GE effort to mount jets on rotor tips probably stemmed from 1943 when the Allies saw that this had been done by the Germans as they captured a Doblhoff helicopter. In that craft, the conventional piston engine drove both a small propeller providing airflow across a rudder with an air compressor to provide air (subsequently mixed with fuel) through the rotor head and hollow rotor blades to combustion chambers at the rotor tips.

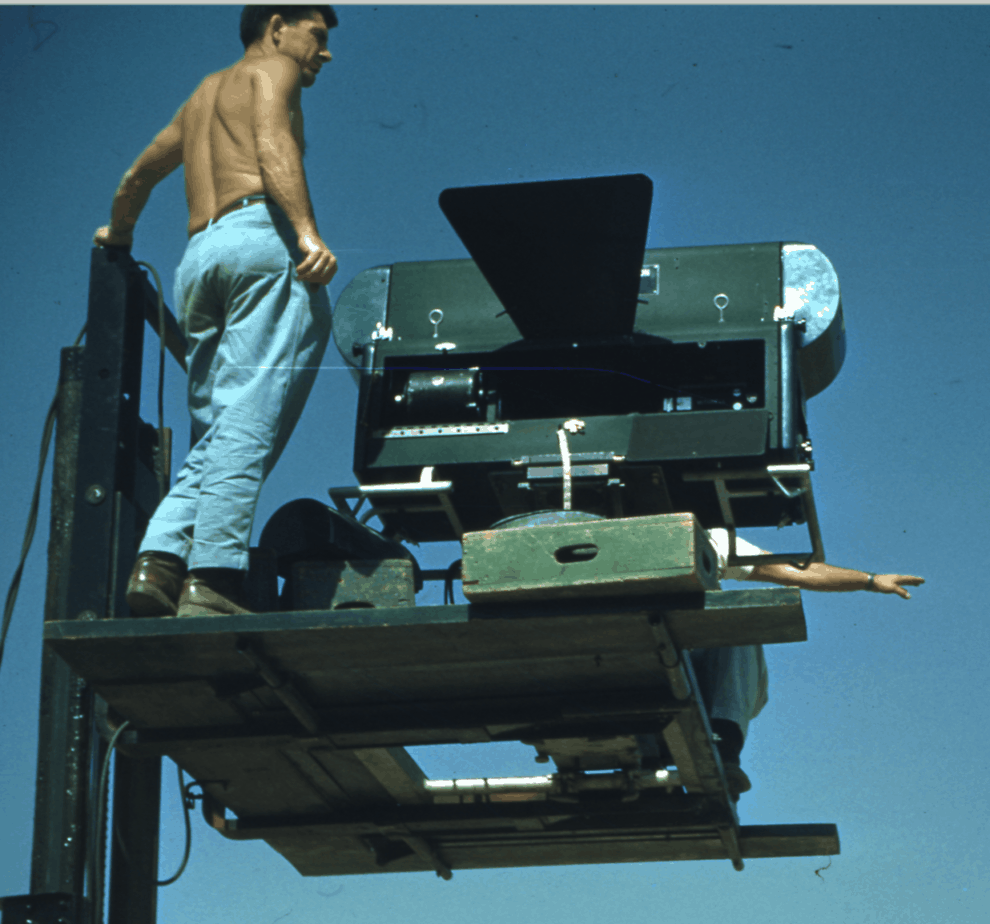

GE’s “Hermes project” planned: … testing of athodyd jet units by means of a whirling arm setup. 12Memo by D. Cochran, April 26, 1946. Job No. 310 GE Correspondence For the Hermes Project, Kellett Aircraft in Lansdale Pennsylvania would manufacture special rotor blades with internal fuel lines to feed the “Athodyd” ramjet at the blade tips. 13GE Memos and Correspondence, Bensen Letter to Everett Lee, April 11, 1945. Testing began March 5, 1945. 14Report by Everett Lee April 11, 1945 GE Correspondence Presumably, Kellett Aircraft’s work on the GE blades laid the basis for its work on the blades of the Flying Crane, a couple years later and can possibly be seen as leading to the “light rotors” of the Hughes designs after 1956.

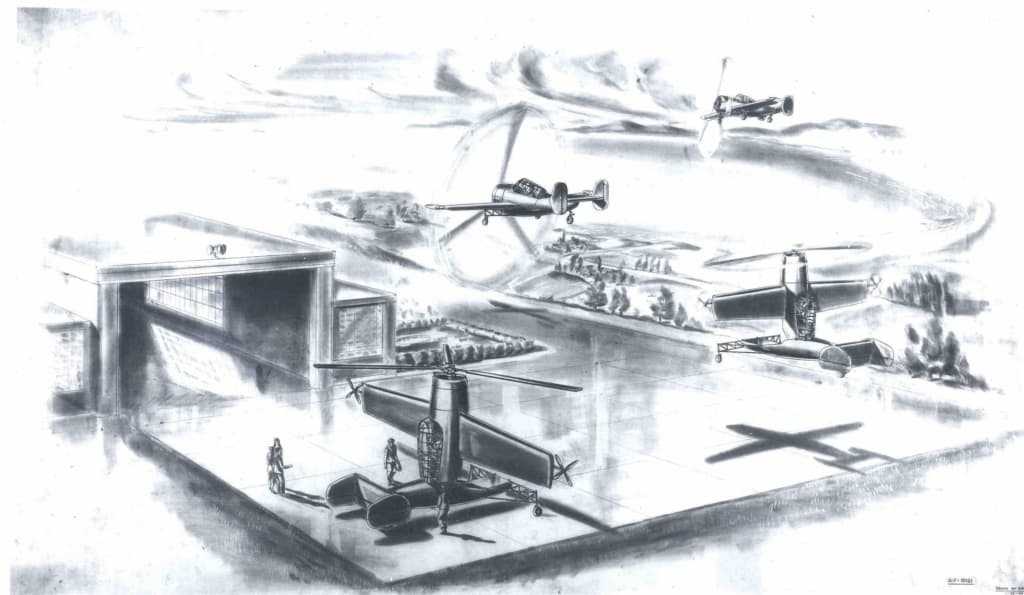

A drawing of the XGEH-2 Heliplane shows how its fuselage faced vertically for takeoff and then hinged down into a typical airplane shape for forward flight. The aircraft would be lifted by a large rotor blade mounted at the front. Torque compensating propellors at the end of the wings would provide torsional stability during the vertical ascent. The fuselage would then fold forward and the craft would fly as a plane–pulled by the same large rotor blade, now acting as a propeller.

Bensen had some military help from Major Wilson at Wright Field in Ohio yet Wilson had no cash to provide for the projects.Through Major Wilson, in early 1945, for the Hermes Project, Bensen obtained two autogyros for no cost. With a rotor blade for lift and a propeller for forward motion, the autogyro had thrived in the 20s and 30s–at least as an experimental craft. By 1945, it was quickly become obsolete. Wilson arranged for two autogyros that had been manufactured by Kellett Aircraft in Pennsylvania–an YO-60-5 and an XR-3. Presumably, the goal was to mount ramjets on an autogyro.

GROUND RESONANCE – wrecking an autogyro

The Kellett YO-60 arrived at GE on February 22, 1945–as Bayer began work there. It was reported that others flew it 7 hours though it isn’t clear who would have done this. 16Report by Everett Lee April 11, 1945 GE Memos and Correspondence Initially, the other donated craft, the XR-3 autogyro, did not arrive. It still needed repair and remained at Kellett Aircraft in Lansdale through the summer to be recovered with fabric and for installation of new torsion rods. 17Bayer referred to the Kellett Aircraft location as “Lansdale”. Kellett often listed its location as North Wales in Philadelphia. The Kellett factory, leased from SKF Ball Bearing in May … Continue reading Bensen wrote that, upon arrival, the YO-60 looked air worthy. The last autogyro model produced by Kellett Aircraft, the YO-60 featured an engine that could briefly engage the rotor blades to allow a jump takeoff. A 1943 video of the craft:

As described online: The two-place YO-60 was designed by Richard O. Prewitt and could do jump take-offs. The rotor was spun up to about 280 rpm (rotations per minute) at a no-lift angle using the power of the radial engine. When ready for take-off, the pilot would release a clutch mechanism which changed the blade angle to 8 degrees. This caused the aircraft to ‘jump’ about 10 feet into the air. The engine and propeller then pulled the YO-60 into forward flight as the rotor angle was decreased to a normal flight pitch of 3 degrees. The engine was only used to spin the rotor up to flight speeds on the ground, while in flight the rotor was free spinning.18http://www.indianamilitary.org/FreemanAAF/Aircraft%20-%20American/XO-60/XO-60.htm

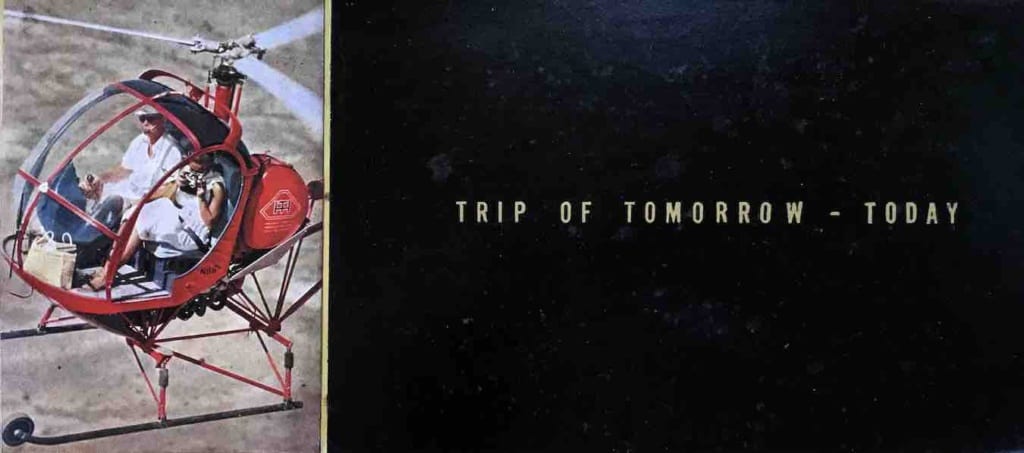

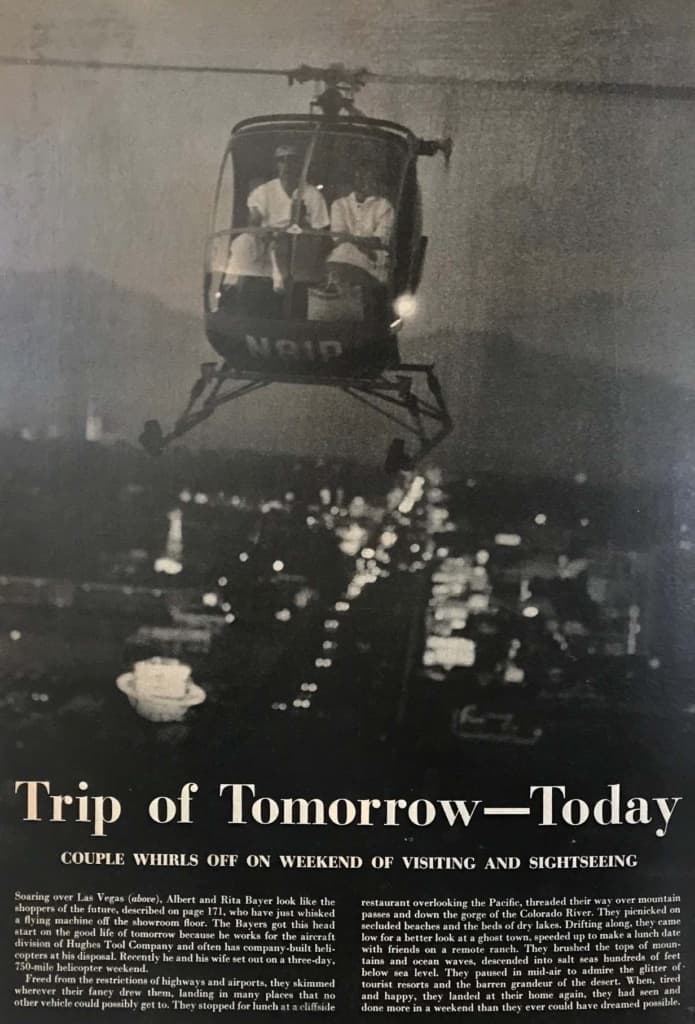

First flown in February of 1942, by 1943 the YO-60 and relate Kellett autogyros of the time were considered obsolete. They tended to be slow and inefficient. 19NASA/CR—2003–212799 An Overview of Autogyros and The aDonnell XV-1 Convertiplane Franklin D. Harris. Oct. 2003 Still, thanks to popular magazines and related newspaper articles, they had left a great impression on the imagination of boys. During the 1920s and ’30s, with its hybrid design–airplane and helicopter–and its appearance of speed plus maneuverability–the autogyro had captured the public imagination–epitomizing the futuristic dream of an aircraft for everyman. The passion felt by Bayer and many of his engineering friends had its roots in this literature of the 1930s-the futuristic aircraft that the common man might park in his driveway. Of all these dreamers, Bayer would be the one to ultimately realize the trip of tomorrow today.

This romantic view was not always shared by critics. 20See discussion of this at https://vtol.org/files/dmfile/62-2006-125Charnov2.pdf in A Critical Re-Examination of the Franklin Institute Rotating Wing Aircraft Meeting of Octr 28 – 29, 1938: Facts … Continue reading Bayer was 9 years old in 1934 when Wallace Kellett, the maker of autogyros in America, talked about a “plane in my garage.” 21The Ottawa Journal

Ottawa, Ontario, Canada 29 Dec 1934, Sat • Page 19

In 1945, in Seattle, Boeing was working on the “hoppi-copter”–an engine with rotor blades that one strapped to their back. 22The Morning Herald (Uniontown, Pennsylvania)25 Jun 1945, MonPage 6 Yet, by 1946, the press was lamenting the failure of technology to put a helicopter in every household. 23Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania)09 Nov 1946, SatPage 48 The problem lay in one fact. Funding for aircraft innovation–similar to technological possibilities in many other areas–only came about when the craft met military needs. Weapons and national security became the method to realize any creative and innocent dreams of innovation.

The YO-60 did not last long at GE. Reporting on progress with the GE convertiplane project in April of ’45, Bensen wrote that, during March, the YO-60 had been “upset by strong gusts after landing”. 24GE Memos and Correspondence, Letter Bensen to Everett Lee, April 11, 1945, p. 2 A couple histories state that Bensen flew the XR-3 in 1943 and then became an accomplished XR-3 pilot. I haven’t … Continue reading This is not exactly what happened. On March 8, on his first and only flight in that aircraft, Bayer severely damaged the Kellett YO-60 autogyro. In his logbook, he wrote that he had “ground looped” due to “ground resonance”.

Ground resonance is vibration set up when an helicopter or autogyro’s landing gear are loosely touching the ground. As the landing gear interact with the ground, vibration travels up through the landing gear and is then amplified by similar frequencies created by the engine and blades. The vibration takes hold of the entire aircraft. This can be exacerbated by the nature of the landing gear. In “ground resonance” the craft’s undercarriage would vibrate at a frequency aligned to the frequency of any unbalance in the blades, setting up a catastrophic vibration that could tear the craft apart in seconds.

The X0-60 was prone to ground resonance. The danger was already apparent to others. By March of 1945, the Army Air Force was in the process of deciding that the Y0-60 was too dangerous to fly any longer.

Kellett engineer Bob Wagner had studied ground resonance in the autogyro. If Bayer had sought training in piloting the autogyro, Kellett’s chief pilot, Dave Driskill, could have educated Bayer on ground resonance before he tried to fly it. He had certainly trained others in the craft. 25https://www.airspacemag.com/history-of-flight/above-amp-beyond-jump-ship-39751500/ Autogyro pilots were routinely trained to recognize the problems of ground resonance and to rapidly change the speed of the blades or lift off–removing contact with the ground and thus immediately halting the destructive vibration. 26https://rotorcraft.arc.nasa.gov/Publications/files/Harris_NASA-CR-2003-212799.pdf

However, Bayer took off in the XO-60 without having had any instruction in it. The wrecking of the XO-60 illustrates the strengths and weaknesses of Bayer’s entire career. This Bayer’s first flight since his final flight for the military in September of ’44. He seems to have been eager and reckless. Absent from Bayer’s logbook is any evidence that prior to flying and wrecking the X0-60 he had had any instruction in the autogyro–or in piloting any rotary aircraft. 27In his letter to Tozer, Bayer makes no mention of any training in the X0-60, but does for the XR-3. His logbooks echo this. Young and eager, Bayer possessed a copy of the craft’s “Flight Operating Instructions”. He seems to have thought reading the instruction manual would be adequate.

The crash damaged the craft’s rotors, propellor and elevators. 28Report by Everett Lee April 11, 1945 GE Correspondence During the following month, April, GE issued a memo stating “…efforts will be made to obtain autogyro ratings for any licensed pilots participating in this program.” 29Memo by C.W. LaPierre, April 27, 1945. Presumably, the memo was directed at Bayer–too late to save the X0-60 yet giving him clear guidance with respect to the XR-3 which had not yet been delivered.

Bayer never talked about this event. Years later, in a resume, Bayer would list himself as having flown 50 hours in the YO-60. His logbook shows just 1 hour–the hour in which he wrecked it. 30AL BAYER Background Resume for Society of Experimental Test Pilots For Upgrade to Fellow. This hour of flying (and wrecking) the YO-60 entitled Bayer to membership in the Twirly Birds. He joined this association for pioneer pilots in 1951. They required members to have flown a rotary aircraft in sustained flight prior to VJ Day, August 14, 1945 and they required a witness. Bayer told them Dave Driskill had see him make a qualifying flight…however no one seems to have witnessed his wrecking of the XO-60.311951 “Constitution of The Twirly Birds” Article III. See http://www.twirlybirds.org/purpose.htm

The culture of test pilots during this period would find Bayer’s precipitous flight of the X0-60 to be normal. While the engineers provided an aircraft whose engine ran, beyond a certain point, the test pilot ultimately had to trust himself. For Bayer, the literal and figurative lesson of the crash became, “don’t be tentative.” One must not hesitate when encountering ground resonance. It was and long-lasting and invaluable lesson. Though this was not his last experience with ground resonance destroying the craft in which he sat.

There was no punishment. And, Bayer learned to take bold, informed steps–never tentative again. And, always, better informed about the technology–moreso than about the expectations or wishes of his employers. Some people would see his approach as egoistical. The dramatic emergence of that trait in Bayer lay rooted in lessons built on personality and forged by experience. Other pilots died or were greatly injured while Bayer survived. In his final years, he often expressed wonder that he had survived.

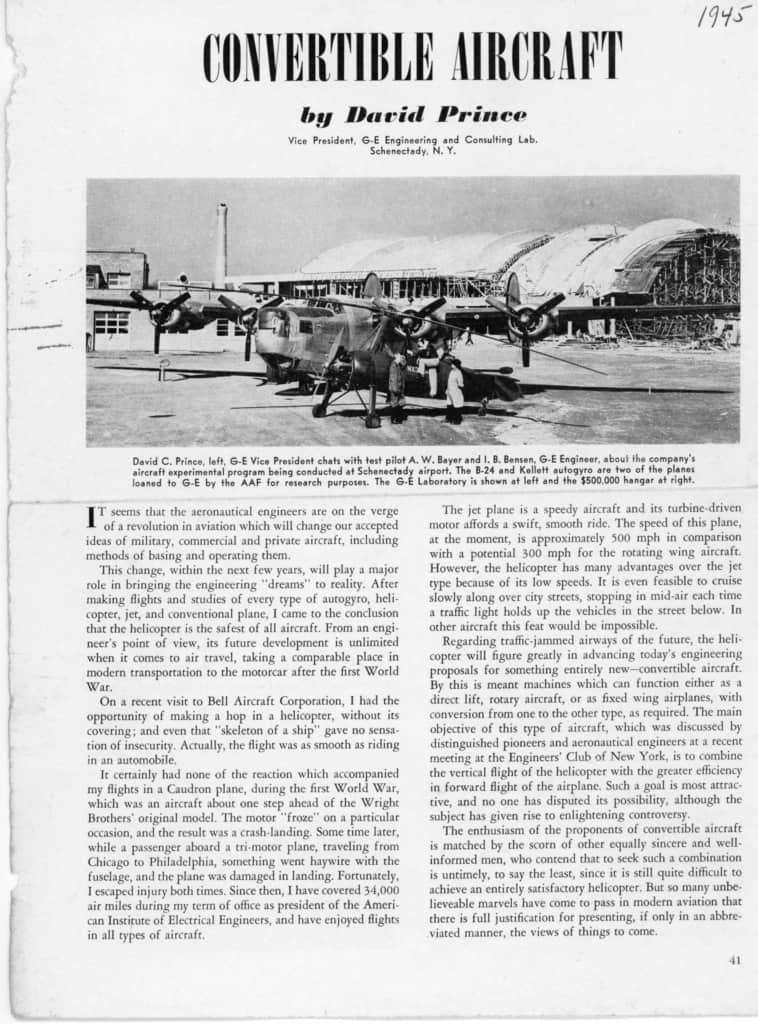

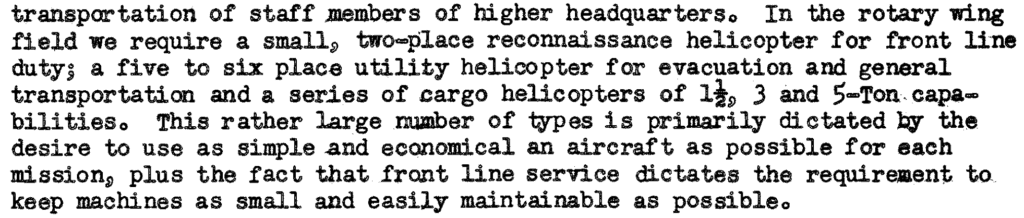

Constructed from the remnant of the autogyro, the X0-60 test rig was placed in the Alplaus hanger–still under construction–and used to test the ramjets. By July, Bensen had fired up the ramjets. 32GE Memos and Correspondence, Bensen to Lee July 12, 1945 GE Correspondence Though, initially, he seems to have hoped to mount the ramjets on an autogyro, Bensen began to see the test rig as critical to the project. There was talk that the test rig itself would be used for a vertical take-off. 33GE Memos and Correspondence, Bensen describes the test rig as being constructed at Kellett Aug. 23, 1945 letter to Prince, presumably the blade portion. For the rig, Kellett Aircraft began building and balancing special blades–“hollow plastic blades” — installing into them fuel and electrical lines for the ramjets. 34Report Bensen to Prince, Aug. 23 1945 GE Correspondence Meanwhile, and even as the test pilot and engineers improvised, GE Vice President David Prince wrote an article stating, “the helicopter is the safest of all aircraft”. He compared it to the state of the motorcar 20 years earlier. Prince, Bayer and Bensen were photographed for an article.

Through the 40s and 50s, Bayer was work for aircraft manufacturers for whom the rotary aircraft seemed more a hobby than a serious effort. This allowed innovation. And, indeed, the eager hobby shop culture of these young men was palpable. Bensen belonged to a Helicopter Club, formed in 1942. On June 10, Bayer helped pilot the club’s model helicopter–operated with a fish pole device–in a demonstration for Prince. 35Members of The Helicopter Club report June 10, 1945, GE Memos and Correspondence Prince left the meeting with Bensen still wanting to show him more. Bensen commented:

We can confess now that if Mr. Prince hadn’t left, we had full intentions of making a helicopter pilot of him too– in one easy lesson.

Though Prince had been the primary supporter of Bensen’s efforts at GE, one might read into this statement some frustration by Bensen at the distance between the geeks or club members with their passion for helicopters and the industry bosses. The latter did not share that passion or have any deep knowledge of rotary aircraft. The whole convertiplane project seems to have been a dream by a marginal coterie of engineers that Bensen seized and then shifted. Ultimately it was not something that GE embraced. For the next decade, military and corporate lack of commitment and funding for helicopters became an ongoing reality as Bayer and the engineers he befriended moved from company to company. For a long time, the military pushed their industry toward size–the large, the big, the cargo craft, the troop carrier, the fighter, the bomber–not toward maneuverability.

Thru the summer of ’45, the XR-3 autogyro remained in Pennsylvania. During that time, Bayer flew locally out of the Alplaus facility, mostly in a Howard DGA-18 and a Stinson Voyager 150. 36Bayer logbook If he was still on the payroll at GE, it isn’t clear that he had much work to do that summer. This, plus his belief that his life would be short, seems to have leant to Bayer’s decision to barnstorm–to fly stunts for local airshows, thrilling the public with daredevil maneuvers as had pilots for decades.

Bensen began to push GE to increase the status of his project. By August of ’45, at least as lauded by Bensen, the Heliplane and Hermes projects at GE included fifteen people with another twenty working at York and Kellett. Bensen wrote up a series of goals that now went beyond the original goal, “data collection”. That month Bensen proposed to his superiors at GE that they create the “Rotary Wing Section” of the GE Laboratory. He lamented the secondary or nominal commitment of the company to rotary wing development. He wrote up a formal rotary project at GE, There will be no need for ‘underground’ helicopter activities in our Company. We can organize and consolidate all timid efforts made by many individuals throughout the Company.

With the XR-3 still not arrived, Bensen wrote: Our Test Rig remains to be the most valuable tool in the search for the most successful airplane-helicopter combination. At the same time, Bensen’s program took into its possession a Kellett XR-8A helicopter into which intended to install a gas turbine engine. Presumably this was the second prototype. Presumably, this would be so that Kellett could manufacture blades with which Bensen could retrofit a XR-8A with jets on the rotor tip powered by the turbine engine with hot gases–a “cold cycle” approach as opposed to “hot cycle” or jets fired at the rotor tips. 37GE Memos and Correspondence, Bensen to Prince Aug. 23, 1945 p2 Bensen seems to have begun discarding the idea of using the XR-3 autogyro even before it had arrived. However, Bayer was expecting the XR-3 to arrive and continued to work towards its use.

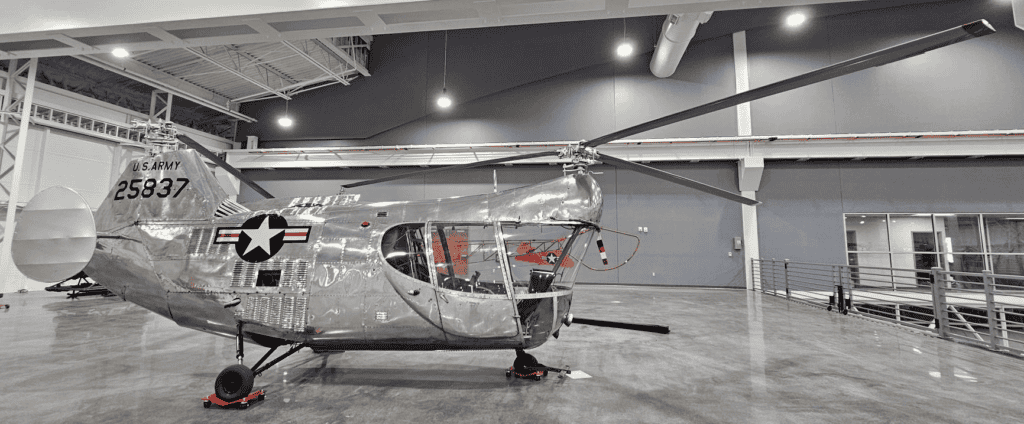

United States Air Force, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. 38https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kellett_XR-8 See the video of the restoration:

As described in the company’s publication, “Design Aspects of the Kellett XR-8 Helicopter”, the XR-8 syncropter first flew in August of 1944. The Army Air Force received a XR-8A in January 1946 and immediately cancelled its XR-8A program. This was probably the second prototype, 43-44714. 43-44714 remained flying at Kellett through 1947. Presumably, GE and Bensen hoped that some of the XR-8A’s problems could be addressed with ramjets–lightening the craft and reducing vibration. Jets at the tips of the blades could ultimately replace the need for heavy engines. It isn’t clear that this idea ever went beyond a notion.

On August 7, 1944, XR-8 43-44714 took to the skies for the first time, becoming the first American synchropter to fly, with Kellett test pilot Dave Driskill at the controls. The flight revealed a lack of directional stability, leading to the addition of two tail fins. However, on September 7, a blade from each of the rotors collided while the aircraft was being flight tested and the issues on 43-44714 were being resolved. The second prototype, XR-8A 44-21908, began making its first test flights in March 1945. In addition to its two-bladed design, the XR-8A was further distinguished by its noticeable rounder tail fins as opposed to the squared examples on the first prototype. Unfortunately, the two-bladed rigid rotors caused severe vibration issues which proved extremely difficult to solve and led to the re-emphasis on continuing flight testing on 43-44714. –National Museum of The United States Air Force, page. 40https://www.nationalmuseum.af.mil/Home/About-Us/ Bayer flew 43-44714 many times between May of 1947 and September of 1947. In his logbook he designated it a model XR-8A–a designation apparently associated with the addition of fins on both XR-8A prototypes after September 1944.

In September of ’45, Bayer traveled to Philadelphia to take lessons in flying the XR-3 autogyro. On September 8th Kellett Aircraft’s chief pilot, Dave Driskill, checked him out in the now repaired XR-3 autogyro. Driskill “signed off” approval in Bayer’s logbook.–rating him to fly the autogyro on Sept. 21. This was Bayer’s first training in a rotary aircraft. 41Bayer Logbook. On September 26, Bayer flew the XR-3 back to Schenectady. 42Bayer Logbook. Account of hours–his document of March 1953, entering McCulloch. Bayer letter to Tozer March 31, 1952, p.1 Letter Bensen to Everett Lee, April 11, 1945, p. 2 GE Memos and … Continue reading

From September to mid-October, Bayer conducted a series of tests, flying the XR-3 from the Alplaus hanger. These included ground resonance tests. His reports described good progress. However, it remained a risky aircraft. Years later he wrote that, on one occasion he “unloaded” the rotor at 1500 ft. while doing a side-slip and recovered at 5 ft above the ground. 43Bayer letter to Tozer March 31, 1952, p.2 The tests resulted in repairs and, at least in the reports, a growing confidence in the craft. 44Reports OCt, 5, 11, 22, 1945 AW BAYER

THE ROTOCHUTE – Igor gets a British idea

Notwithstanding the idea of adapting the worn out XR-3 and the bulky and dangerous XR-8, by late 1945, Bensen’s ambitions at GE began to scale down in size. His ideas for a Rotary Section seem to have found little support among management. The idea of using an XR-8 helicopter for ramjets seems to have fallen by the way and Kellett would instead soon deliver it to the military. Bensen wrote Major Wilson:

I would like to try out ramjet application on a small, light machine with almost no fuselage at all, which we could make fly with ramjets”. He wrote that Major Wilson suggested:

… the ‘rotochute’,–an obsolete piece of equipment, donated to AAF by British about two years ago, which was since put away ‘collecting dust’ in the hangars. Although, he felt, the machine cannot be used as is, it could be reworked for our purposes. 46Bensen, Memo. Oct. 22, 1945.

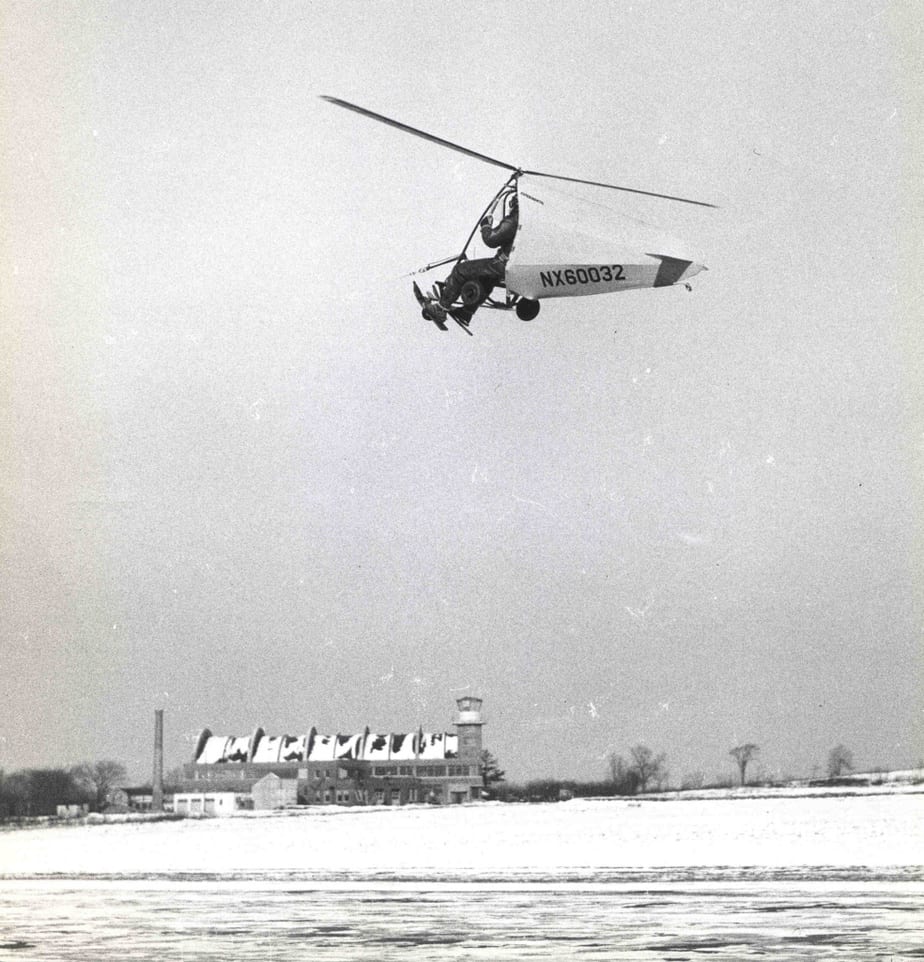

Wilson provided Bensen with the British, Hafner Rotochute–an unpowered rotary “parachute” that the British had ceased testing in 1943. Initial flight testing fell to Bayer. 47http://jcmservices.net/BensenHistory.PDF Bayer later wrote:

We also were given a British Rotochute (an autogiro glider which had an open seat, a rotor, a tail and a couple of skids. I taught myself to fly it by tying it behind an airplane slip stream, like a wind tunnel, and then flew it around the airport towed by a truck on the runway. Some years later while touring the British Army Aviation Museum at Middle Wallop, with the commanding general, I saw a rotochute hanging from the ceiling. The general told me that it flew only once and killed the pilot. I then told him about my experience with one and sent him a photograph which now hangs in the museum. 48Unbelievable.

Wilson worried that the XR-3 might fail and opined that the remnants of the YO-60 were worn out. In addition to the Rotochute, another opportunity for learning about the practical application of ramjets had appeared. Wilson asked Bensen if he could test one of the Army’s recently captured German Doblhoff helicopters. In that helicopter, compressed air from the engine and kerosene mixed with that air powered jets on the tips of the rotor blades. 49Porter p 34 Wilson provided encouragement to Bensen yet told Bensen that he couldn’t provide money. 50Memo, Oct. 22, 1945

Testing of the XR-3 continued into November using parts salvaged off of the wrecked X0-60. In December of ’45, Bayer received a letter from the Civil Aeronautics Administration advising him to read its Glider Airworthiness document prior to flying the Rotochute. By early 1946, Bensen seems to have fully shifted to modification of the Rotochute.

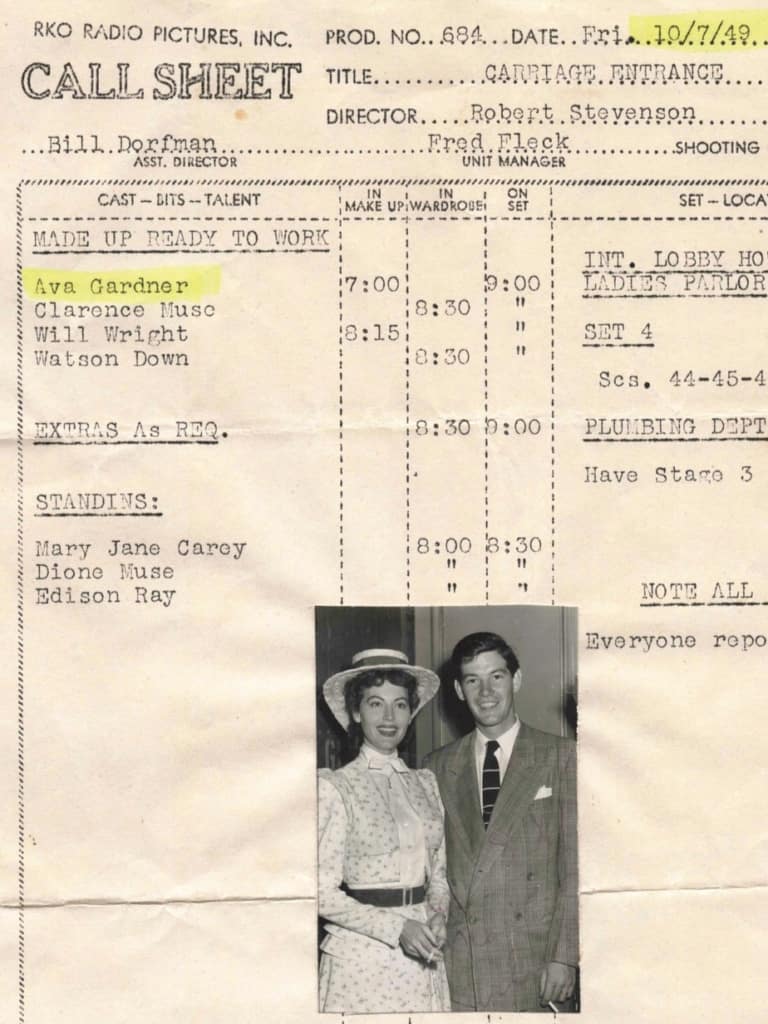

NEVER DID SEE IT – courting

During early 1946, Emma Cusask and Alice Bayer met while twisting wires for the war effort at the main General Electric plant in Schenectady. During March, the mothers arranged for their children– Al and Rita–to meet. 51Letter AL TO RITA, Nov. 25, 1946

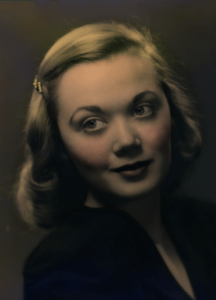

On their first date Bayer drove Rita to Newman’s Lake House in Glen Falls. Rita loved to swing dance. On the way, they stopped at the airport to see a P-47 Thunderbolt. Apparently, because they were necking, Bayer “never did see it.” 52LETTER AL TO RITA MARCH 15 1947 Rita was beautiful. Bayer’s letters suggest that he was completely smitten.

During May of 46, Bayer gave Rita his wings–they became engaged. 53LETTER BAYER TO RITA MAY 23 1947 They set their wedding date for July of 1947. A Catholic girl, Rita Cusack had graduated from The College of St. Rose in Schenectady during spring of 1946. She suffered a short bout of polio. In the fall of 1946, she entered nursing school.

Rita would never practice nursing. She would marry Bayer and become a housewife. Her father, Clarence, disliked this prospect. He wanted her to move up in a nursing career. Neither of her parents liked Bayer. With wishful thinking, Rita’s mother predicted the marriage would only last two months. 54LETTER BY Bayer Jan 14, 1947 Rita’s parents told her that Bayer seemed to be a lazy “braggard”. 55Letter by Bayer, Jan 19, 1947

Rita (my mother) told me that she married Bayer because he danced so well. Eventually, once married, she had a big house, nice things. As Bayer became busier and busier with work and, particularly after 1960, she volunteered in the local community. Rita continued to write to her parents about how well things were going with her life. My recollection of the extended family in upstate New York during the 1950s and 60s is that they always regarded the couple’s move to California as an aberration that could be corrected. They invited me to return and live in the East. They seemed to have no notion of how different life in California might be from life in upstate New York, and no appreciation of my father. He was the successful and somewhat strange relative. No one in her family had any idea what he actually did for a living.

THE HAMMERHEAD STALL – reasons not to barnstorm

Today, in Schenectady, the old GE Alplaus hanger houses The Empire State Aerosciences Museum. When built it featured a heated concrete floor. During spring of 2001, as we drove away after a visit, my father, Al Bayer, told me why he decided to cease barnstorming.

One day while barnstorming at an airshow, he told me, he had flipped his biplane upside down, five feet off the ground, flying along the runway as the audience gasped in wonder, his body hanging upside down from a harness in the cockpit, his head a few feet above the ground, thrilling the onlookers. It appears he shifted to a biplane for just one event, and it didn’t go well. This near mishap in a biplane seems to have occurred during April ’46. According to his logbook, Bayer only flew a biplane one time that year–a WACO UPF. 57Bayer logbook He barnstormed mostly in the low-wing Howard DGA-18

However, on the day he to the WACO barnstorming, he experienced a problem. The biplane’s gas tank resided in the upper wing, which, when the plane was upside down, became lower than the engine. In normal flight, gravity fed gas from the tank in the upper wing of the biplane down to the engine. With the plane inverted, the tank lay below the engine. The engine could run dry and stop. There were a few moments while the engine still pulled gas from the line. The trick, he told me, was to count and flip the plane right side up before the engine quit. I imagine he had learned this while flying the Stearman biplane in Army flight school. However, this time he counted too slowly and the engine stalled while he was just above the ground, upside down.

I pulled the plane straight up a couple hundred feet into a hammerhead stall, flipped it nose down and landed. The audience, of course, thought this was all part of the show and applauded. Next day, I went up to practice. I’d use flat, stratospheric clouds, pretending that they were the ground, and roll the plane over above them and then count. That next day, I rolled the plane over and accidentally dipped my head into the clouds. I decided not to barnstorm anymore and to be more careful. 59Story to me by Bayer, 2001. The hammerhead stall is a tricky maneuver yet quite impressive. 60http://www.britishaerobaticacademy.com/blog/stall-turn

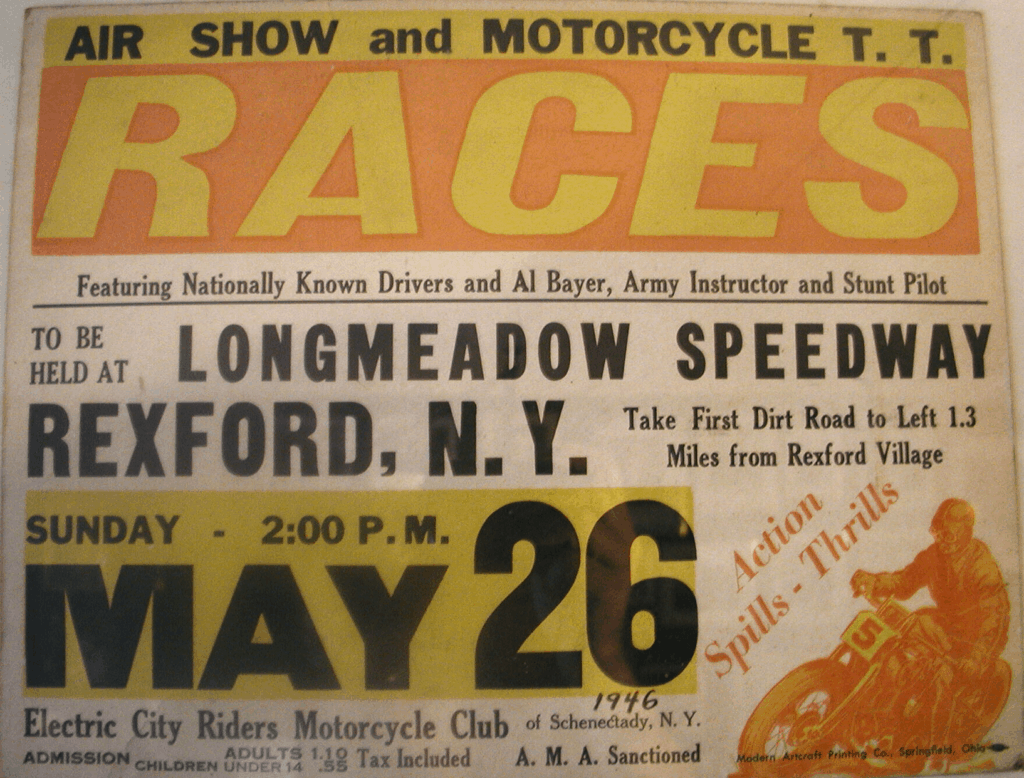

He also flew a Fairchild PT-23. 61He seems to have mistakenly labeled it a Fairchild PT–13 in some of his lists. Though he saved a poster advertising “Al Bayer, stunt pilot” for a May 26 airshow at Longmeadow Speedway, Bayer’s logbook shows that he did not fly on that date. He appears to have quit barnstorming the week prior to the show, apparently after flying the WACO biplane.

For Bayer the danger of barnstorming was amplified by changes in his life. By spring of ’46, he was engaged to be married. Suddenly it seemed that he might not die of cancer. Though he still wasn’t sure of this. Having given up on barnstorming, reconsidering his mortality, thinking about a future, with Bensen’s GE projects reduced to the Gyro-glider, Bayer decided to look beyond GE in order to pursue a career in flying. He had now met Dave Driskill.

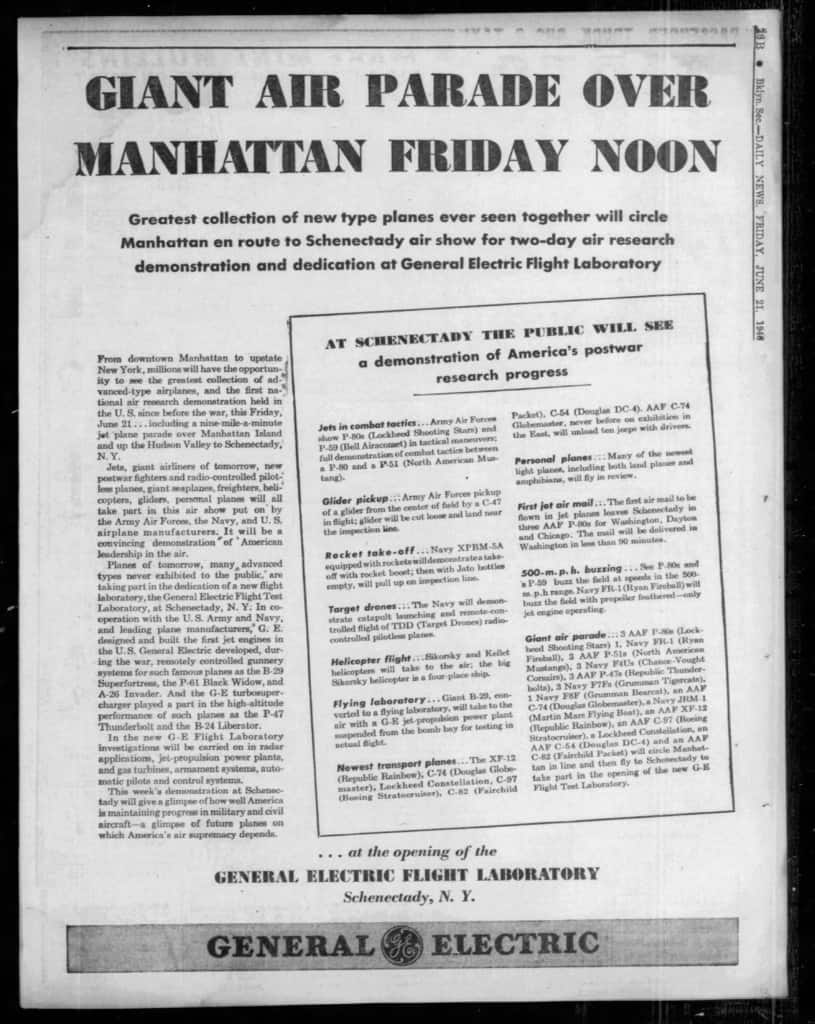

THE GIANT AIR PARADE -air research

By 1945, problems with the XR-8A design lead Kellett to supersede it with a newer design–the XR-10, designed through 1945 and under construction in 1946. 62For gas turbines in helicopters see https://www.danubewings.com/helicopter-turbine-engines/ It was this craft, the XR-10, that Driskill recruited Bayer to help test in spring of ’46–work to begin in January of ’47. Bayer left GE’s employ in May of 1946. He worked for Haven’s Flying School from June ’46 till October of ’46. 63Unsigned contract, June 1946, Haven Flight School at Schenectady County Airport. Personnel Security Questionairre for Hughes Aircraft, c.1949 During spring of ’46, his last act at GE lay in putting himself into their airshow.

On June 21 and 22, General Electric held the public grand opening of its new Alplaus hanger–the Air Research Center. Dozens of planes flew in from across the east coast. An employee of General Electric, Richard Lockett attended and took pictures of the event. (A book of his photos is available.) Visiting planes flew over Manhattan before arriving at the show in Schenectady. 64Ad for Air Parade: Daily New, New York, June 21, 1945 p535.

At the time, General Electric owned two B-24 bombers converted to laboratories for testing radar and gas turbine engines, a B-29 and the Kellett XR-3. 65The Troy Record, June 18, 1946. An airshow was held in Schenectady June 22, 1946. Dunkirk Evening Observer June 22, 1946 p. 1 Bayer saved a couple of photos from the Demonstration. His interest lay in helicopters. These show the Brantley B-1 helicopters, the Sikorsky R-6 and the Kellett XR-8A.

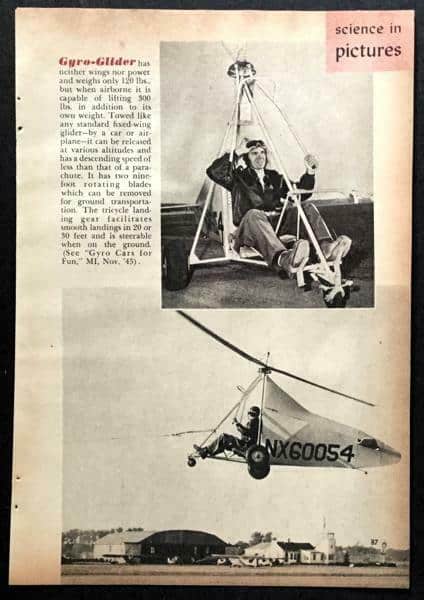

Bayer also took a photo of Bensen’s modified Rotochute–then called a Gyro-glider. The Gyro-glider was exhibited without the cowling so that visitors could see its workings.

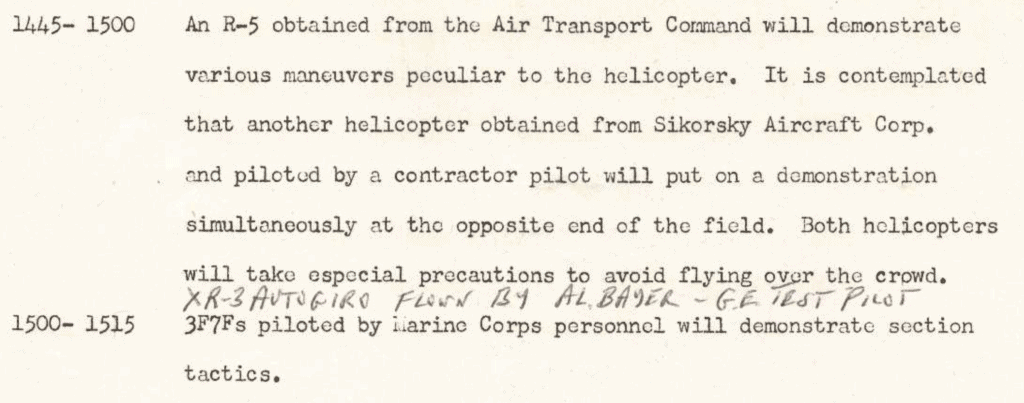

Neither the XR-3 nor the Gyro-glider were printed as appearing in the program for flights during the Air Research Demonstration”. Apparently noticing this, Bayer literally hand-wrote himself into the agenda and then flew the XR-3 during the presentation. 66Air Research Demonstration, Friday itinerary.

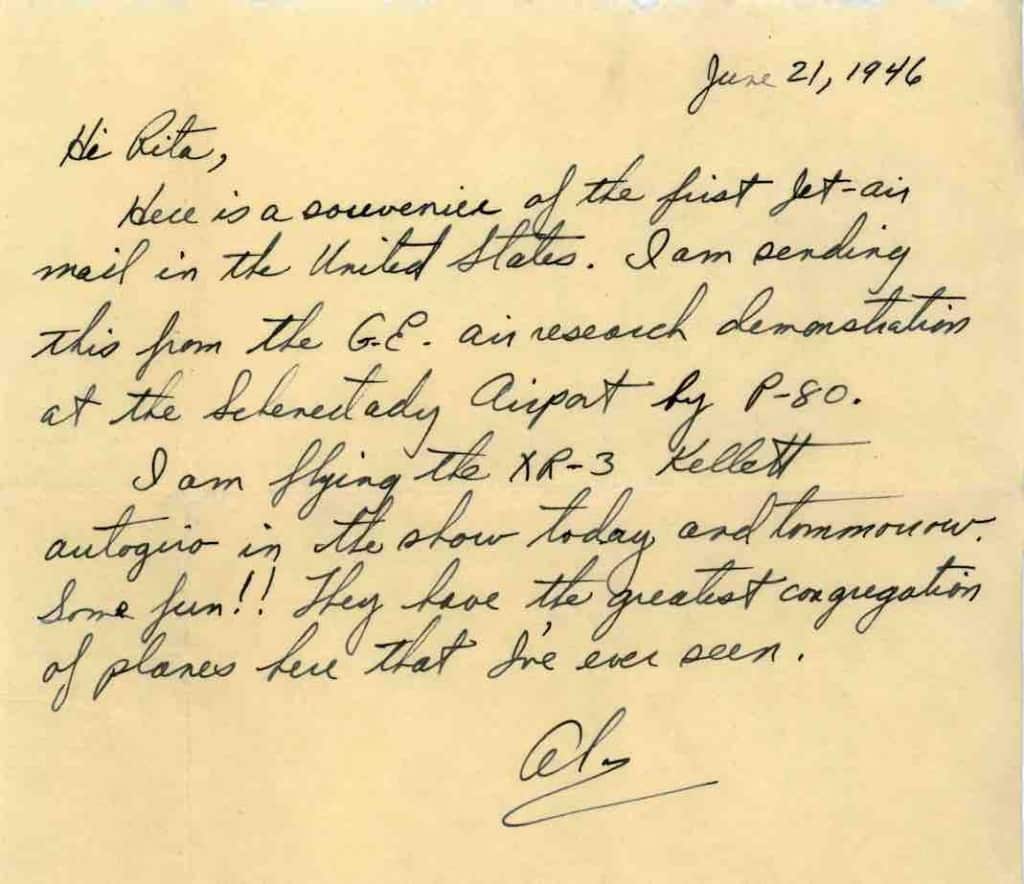

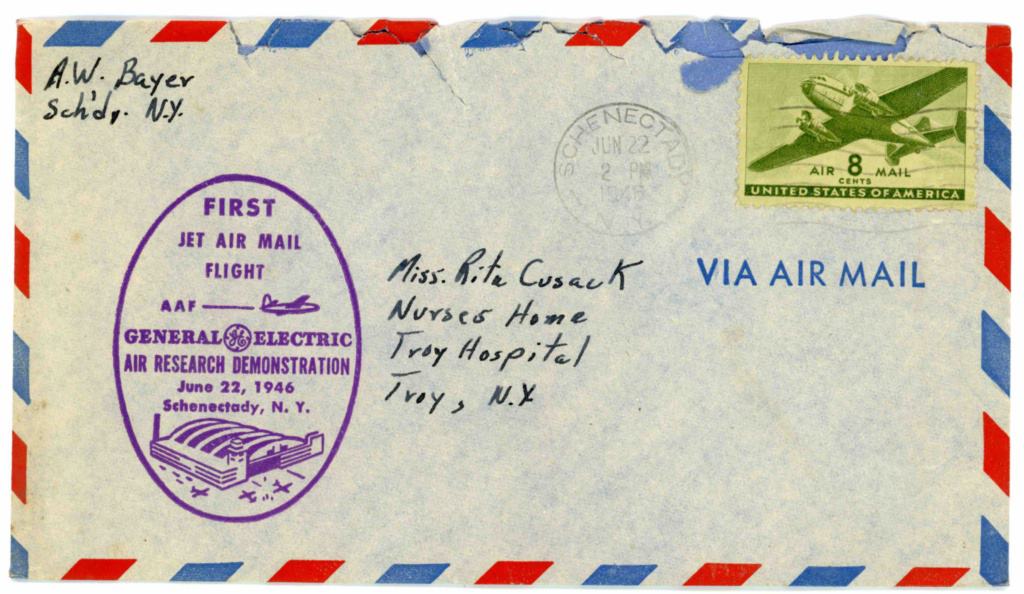

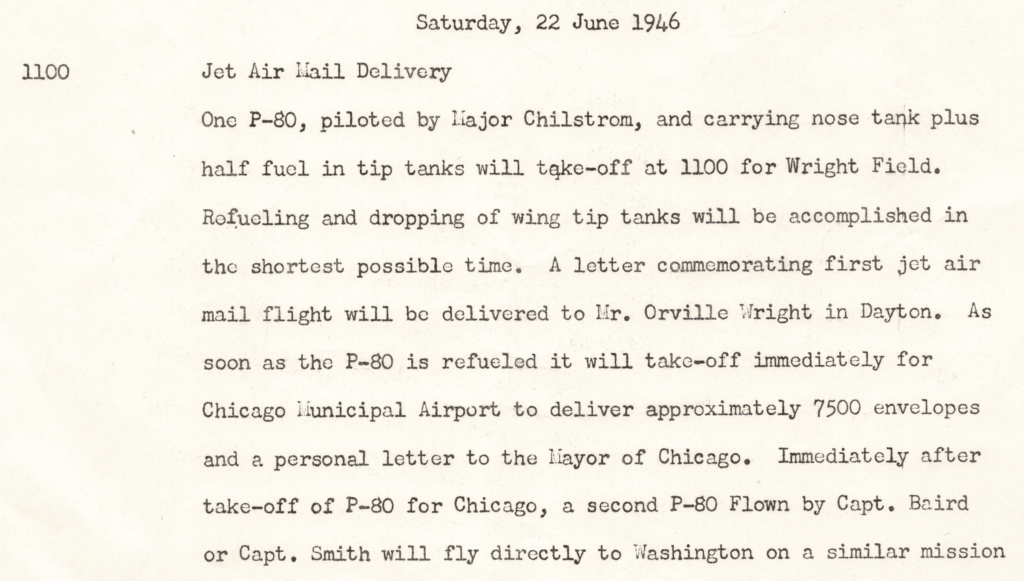

In a letter, Bayer proudly wrote Rita that he would fly for the event on both June 21 and 22. 67Letter Bayer To Rita June 21, 1946 Bayer sent Rita a letter by Lockheed P-80 “Shooting Star”– the nation’s first jet plan mail delivery flight–one of about 7500 specially printed envelopes for the event. Announced in 1945, the P-80 was, at that time, the world’s fastest plane.

At the show, Bayer seems to have talked to Dave Driskill from Kellett Aircraft. Driskill had arrived with square finned, original XR-8A to fly it at the show. Driskill had instructed Bayer in flying the XR-3 the previous September and Bayer may have flown with him in the XR-8A at the Research Demonstration. 68Bayer Postcard June 29, 1946 describes flying in the XR-8. This may be a different air show. In a newsreel of the event, the P-80 was given special status because GE had developed its jet engine. In the video, Driskill can be seen flying the XR-8A at 9:52.

Below, a home movie shows the GE hanger, planes and surrounding countryside around summer of 1946. Separate from the big event in June, we see a bucolic location and daily workers.

Bayer probably talked to Driskill about working at Kellett Aircraft–where they were planning completion of the XR-10 for that fall. Driskill seems to have seen an opportunity to retire from Kellett, ultimately leaving Bayer in his place.

THEY WEREN’T GOING FOR IT

In October of ’46, Bensen announced to the press his “Gyro-glider”–a 120 lb. unpowered vehicle with a payload of 300 lbs. He launched the craft by towing it with a jeep. 69It has been claimed that the Gyro-glider was launched from the bomb rack of the XR-3 but I can find no evidence that this happened. http://www.gyroplanepassion.com/Igor_Bensen.html With removable blades, the gyro-glider was promoted as loadable in your station wagon–a realization of the dream that everyman could someday fly around the block. 70Middletown Times Herald MIDDLETOWN, NEW YORK, Nov. 1, 1946 p.9. Star Gazette Nov. 1, 1946 p. 1 The 120 lb B-1 simplified the articulated rotor of the Rotachute into a semi-rigid design and incorporated an overhead control stick reverser for better control of the rotor.

Though he remained involved with G.E. in assessing the German Dublhoff helicopter, Bensen was soon on his own in pursuing his rotary ideas. He learned to fly the XR-3 and the Dublhoff–eventually suffering severe injuries after the latter went into ground resonance and flew apart. The crash of the B-1 Gyro-glider led to development of the B-2 which featured all-metal construction. 71http://www.gyroplanepassion.com/Igor_Bensen.html

Bayer later wrote to Rita of GE’s lack of interest in Bensen’s ideas, “they weren’t going for (it)“. 72Letter Al To Rita, Jan. 19, 1947 This would not be the last time Bayer found the captains of industry distant from the dreams of men passionate about small rotary aircraft. The small helicopter, autogyro and convertiplane, long remained a sort of toy, a quirky technology to be talked about by young engineers but barely funded. For a long time, no one seemed to have any idea of what it might actually do or be used for–particularly as used by the military.

THEY MUST THINK THAT I’M CRAZY

During September of ’46, Bayer drove from Schenectady to Lansdale Pennsylvania. There, more than anyone else in Bayer’s life, Dave Driskill provided the mentorship in rotary aviation that Bayer needed. 74Postcards from Al to Rita, Sept. 1946. Also letter, Bayer to Tozer, March 18, 1952

A pioneer aviator, the first licensed helicopter pilot in the nation, during 1919 Dave Driskill (1897-1949) had opened an auto repair shop before shifting his interest to airplanes. The question arises, why would Dave Driskill want to hire Bayer to help him test the XR-10. Surely, he knew that Bayer had wrecked the XO-60 after attempting to fly it with no actual instruction. Why then did Driskill want Bayer by his side? Probably because Dave Driskill wanted a risk taker. Many years prior, Driskill had taught himself to fly the airplane in the same way–with no instruction. As described by Casey Huegel in an article about Driskill’s work for the National Park Service:

One day at the field, while Crane was out of town, Driskill decided to see if he could fly the plane. Already he had mastered the art of starting the Jennie [Curtiss JN-4 trainer]. So that part of his adventure was easily accomplished.

Then, as no one was present to tell him not to do it, Driskill taxied up and down the dirt runway several times. Then he did it. Manipulating the controls as he had seen Jimmy Crane do it, he was soon airborne and thus he became one of the few pilots living today who can claim the distinction of being a self-taught aviator . . . thus with no actual instruction, Driskill became a pilot. 75The North Carolina Historical Review, Dave Driskill, The National Park Services, and Aviation on the Outer Banks, 271, Vol. XCV, No 3 July 2018

The culture of the test pilot valued–required–taking risks. The era fostered a sort of insane bravado that propelled men forward and sometimes got them killed. During 1941, Driskill used an autogyro to survey Colonial National Historical Park. In 1942, he was hired by Kellett Aircraft. His experience with the X0-60 somewhat mirrored Bayer’s experience.

“In 1943, Driskill was injured testing an YO-60 autogiro after the machine oscillated so violently that the controls almost knocked him unconscious.” 76The North Carolina Historical Review, Dave Driskill, The National Park Services, and Aviation on the Outer Banks,271, Vol. XCV, No 3 July 2018

Prior to Bayer’s arrival, Driskill may have been the only one at Kellett to fly the XR-8A.

Attempting to fix problems with the XR-8A and be even bigger, the XR-10 was a monumental project for its time–perhaps too bold. The story of Bayer and Driskill at Kellett climaxed is disaster.

With Sikorsky’s successful flight of a helicopter in 1939, Wallace Kellett saw a need to turn from autogyros to helicopters. 77https://www.verticalmag.com/features/21585-stirring-up-innovation-html/ In January of 1943, Kellett was awarded a $1-million military contract to build two intermeshing rotary-wing helicopters that would be designated as the XR-8. Driskill first flew the XR-8 on Aug. 7, 1944. Almost immediately, the blades collided. Kellett modified the craft from a three blade to a two blade intermeshing system and added stabilizers–creating the XR-8A. Both the first prototype and the second were then designated XR-8A. Cost kept the company from a rigid rotor system and it stuck with a flexible rotor system 78Vertical Magazine. Stirring Up Innovation Posted on by Bob Petite https://www.verticalmag.com/features/21585-stirring-up-innovation-html/. This flexible rotor system reduced weight–a major issue–yet made blade collision an ongoing problem. In Oct. 1944, the company obtained a contract to build the larger successor craft–the XR-10. Below, the second XR-8A demonstrates mail delivery in Philadelphia, 1945. The pilot is probably Dave Driskill.

During September of ’46, as Bßayer arrived in Pennsylvania, Driskill said to him: “You couldn’t have come at a better time.” In ’46, the government turned over the Manteo, North Carolina, airstrip for civilian use. By April of ’46, Driskill was planning to run an air taxi service from Manteo and would soon plan to manage the strip. 80The air taxi plan appeared in numerous papers. Including: News and Record Greensboro, North Carolina, Tue, Apr 16, 1946 · Page 5

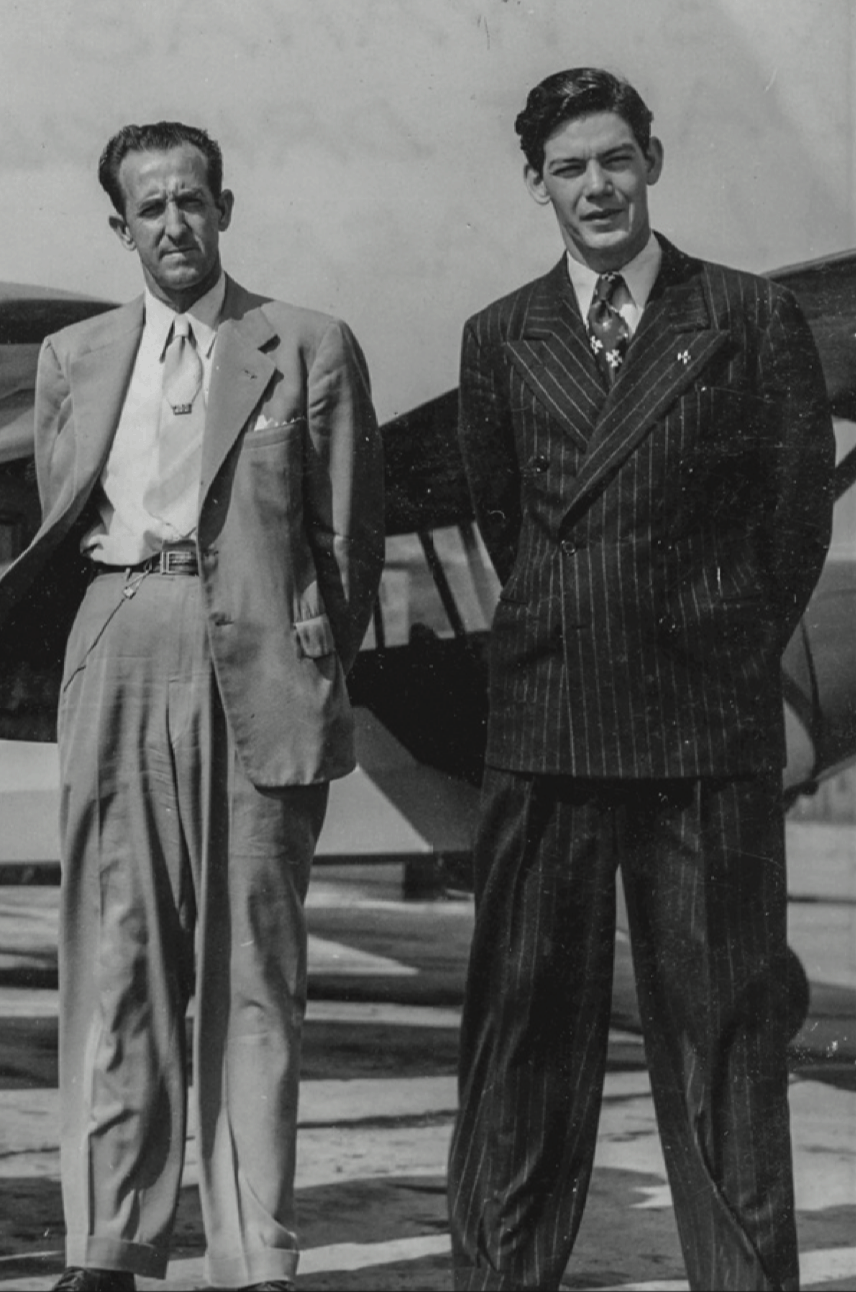

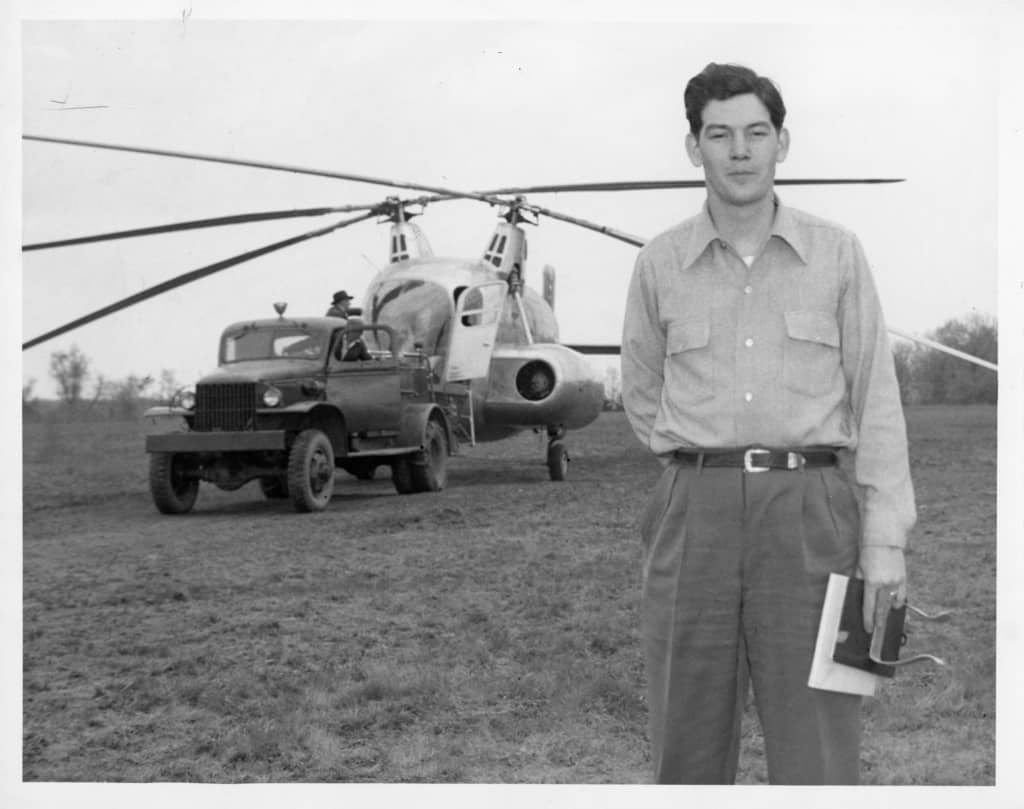

It appears that with the XR-8A project largely completed and Kellett moving on to the XR-10, Driskill intended to step back and, at some point, have Bayer take over the Kellett test piloting. That fall, he needed help from Bayer, flying with him to Manteo so that he could fly a plane back to the Kellett factory. With that plane he could commute to Manteo. Though he served as Kellett’s chief pilot, Driskill would now also be busy helping a banker, Robert Wahab, establish a commercial aviation network while taking over management of the Manteo airport in Dare County. 81Huegel article p 252. Today, the Dare County airport museum contains an exhibit about Driskill. A photo taken in North Carolina during their trip shows Bayer looking young and bit foppish next to the older pilot. 82The North Carolina Historical Review, Dave Driskill, The National Park Services, and Aviation on the Outer Banks,271, Vol. XCV, No 3 July 2018 Driskill was 48. Bayer was 22.

On September 15, the two men flew to Manteo and Bayer helped fly the other plane back to Pennsylvania. 83Sept 15 1946 LETTER by AL BAYER They checked local airports as part of Dave’s charter service and did some landings on a beach at Oracoke Island. 84LETTER by AL BAYER, SEPT 22 1946 During this trip, Al wrote his “first real letter” to his fiancé, Rita Cusack, back in Schenectady.

Video of Dave Driskill flying the XR-8A

Bayer returned to Schenectady and logged a final 3.5 hours in the XR-3 for GE. 85Bayer Logbook As documented in his logbook, at this point Bayer had flown 48.91 hours in an autogyro. According to his logbooks, Bayer had as yet flown no hours as pilot of a helicopter. However, in his summary of hours submitted October 15, 1946 to Kellett Aircraft he wrote that he had flown 200 hours in an autogyro and piloted a helicopter for 20 hours. 86Kellett Memos and Correspondence. Resubmitted with 30 hours additional helicopter time in 1947

THE LAST FLETTNER

Two German Flettner, Fl 282, helicopters were surrendered to American Forces in May 1945: Fl 282 V12 – FE-4614, Fl 282 V23 – FE-4613. Flettner 4613 seems to have initially been kept at Sugar-Bob Airport near Pittsburgh. 87LETTER, AL TO RITA, March 17, 1947 Presumably this was done to seclude the machines near repair facilities at Pittsburgh Army Air Base. 88https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pittsburgh_IAP_Air_Reserve_Station Wilson’s observation about the Flettner design requires some observation on one of the ongoing and major mysteries in helicopter development history. 89FE-4613 Flettner Fi.282V-23 Kolibri‘C1+TW’ Luftwaffe. (Werk Nr. 280023)Geschwaderkennung CI+TW. Transportstaffel 40 (TS/40) – the Luftwaffe’s only operational helicopter squadron … Continue reading Only when the American military had a captured Flettner to test and ultimately fly did Americans– Bayer, Wilson and others–personally see its details. Still, Americans were aware of the Flettner syncropter in general as early as 1938 and this may well have, in general, influenced the Kellett design. Kellett’s efforts was almost certainly inspired by the German design as seen before the war. Per Steven Coates: One of Flettner’s aerodynamicists, Dr, Gerhard Sissingh wrote in 1981 that Richard Prewitt (then of Kellett) visited Flettner pre-war and saw a barely covered model of a Fl 265 which no doubt strongly influenced thinking.

About Nov. 12, Bayer arrived back in Lansdale 90POSTCARD NOV. 12 1946 and was formally hired by Kellett Aircraft. 91Postcards from Al to Rita, Sept. 1946. Also letter, Bayer to Tozer, March 18, 1952 Tests of the XR-10 seem to have been scheduled for January so he had some free time. 92LETTER by AL BAYER, DEC 9 1946 p.3 He went out to look at a captured German helicopter. Col. Wilson stated that, unlike the XR-8A, the Flettner did not suffer blade interference, the problem that plagued the Kellett designs. (Though this does not seem to have been true, given how one of the captured Flettners wrecked.) As evident in Bayer’s snapshot, the Flettner 282 that Bayer examined still retained German markings. 93Bensen Memo, Oct. 22, 1945 Apparently, they asked him to fly it and he refused. Bayer wrote to Rita that one of the Flettner’s had crashed, killing two pilots.

…we are going out to a field near here where there are two German Fletner Helicopters that are being assembled for the Army. We are supposed to inspect them. The army may want me to test them after they are ready to fly, some time after the first of the year. That will be a rough job. Two A.A.F. pilots got killed at Wright Field trying to fly one. (They must either think I’m crazy or that I’m good, but I’ll try it if they want me to. That is, before I get any dependants.) 94LETTER by AL BAYER, DEC 9 1946 p.3

This seems an exaggeration for her sake. Apparently, one Flettner had wrecked but the pilot was not seriously injured. Steven Coates wrote: Helicopters of the Third Reich -Luftwaffe Classic 10 Hardcover – April 17, 2003. It seems the Fl 282 V12 was flown somewhat unsuccessfully at Freeman Field by Capt. H Ray White. He recalled: “The helicopter had been uncrated. They needed someone to run it up. There was no one with any experience available, so I agreed. My only flight in the Fl 282 was over before I knew it! I’m still not sure what happened. I believe the blades made contact with one another, the helicopter toppled onto its side and was a virtual write off. My only injury was a scratched thumb!” It is strongly suspected that the rotor governor linkage was connected in the reverse direction causing its malfunction. Unfortunately, it hasn’t been possible to determine the exact date of this accident or indeed unearth any further detail.

The wrecking of one Flettner lead to Prewitt Aircraft Company of Wallingford receiving a contract by Air Materiel Command to evaluate the FL282 such that it cannibalized both Fl 282s to produce a composite machine for testing. Prewitt had of course previously worked for Kellett and indeed Kellett also expressed an interest in securing this contract. Dave Driskill undertook these flight tests, presumably under contract and of the helicopters he had flown, he considered it “the simplest and easiest to fly“. The completed report was released in September 1948.)) Bayer seems to have tagged along to fly the Flettner once.

When, during WW2, with the XR-8A, Kellett built a syncropter, with two sets of intermeshing blades that mimicked the Flettner–and that ultimately suffered similar issues with colliding blades. It seems to have been designed to meet the military’s desire for a large cargo, troop and rescue craft. An inherent problem however, would be the weight and complexity of the transmission. The Germans used pulse jets on their rotor tips and this greatly lightened the design–hence American interest in pulse jets after the war. The Flettner was small and highly maneuverable, as evident in both Nazi and American videos of the craft. After WWII, as Bayer and others saw the Flettner’s small maneuverable design, it may well have influenced their vision of a small, maneuverable helicopter. However, the syncropter as viewed by Kellett and military during the immediately after the war–the XR-8A and XR-10– was massive and heavy.

Video of American military tests of the Flettner 282.

In June 1940, Kellett had begun work on a syncropter design. Kellett seems to have heard of Flettner’s 1938 syncropter, the FL-265. In November of 1941, Kellett submitted the idea of a syncropter to the military and in September 1943 signed a contract to build two XR-8A airframes. 96Kellett’s Eggbeaters: The XR-8 and XR-10 Roger Douglas Connor, Curator, Vertical Flight Collection Smithsonian Institution National Air and Space Museum Washington, D.C., Presented at the 64th … Continue reading The XR-8A ultimately suffered unfixable problems with stability and rotor-blade collision.

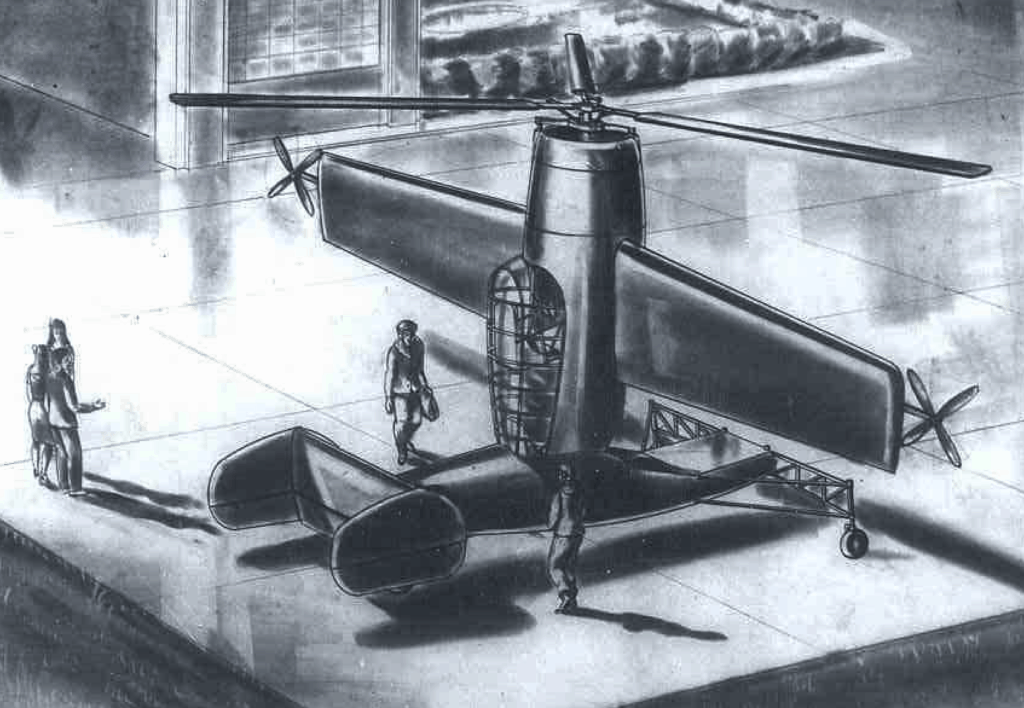

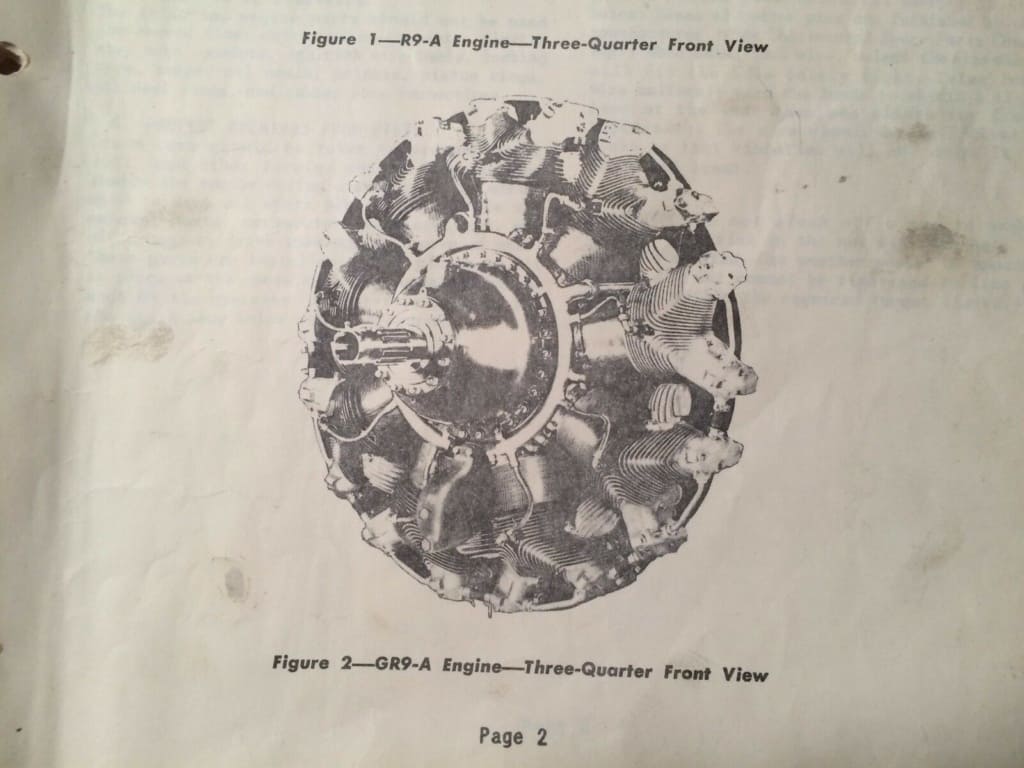

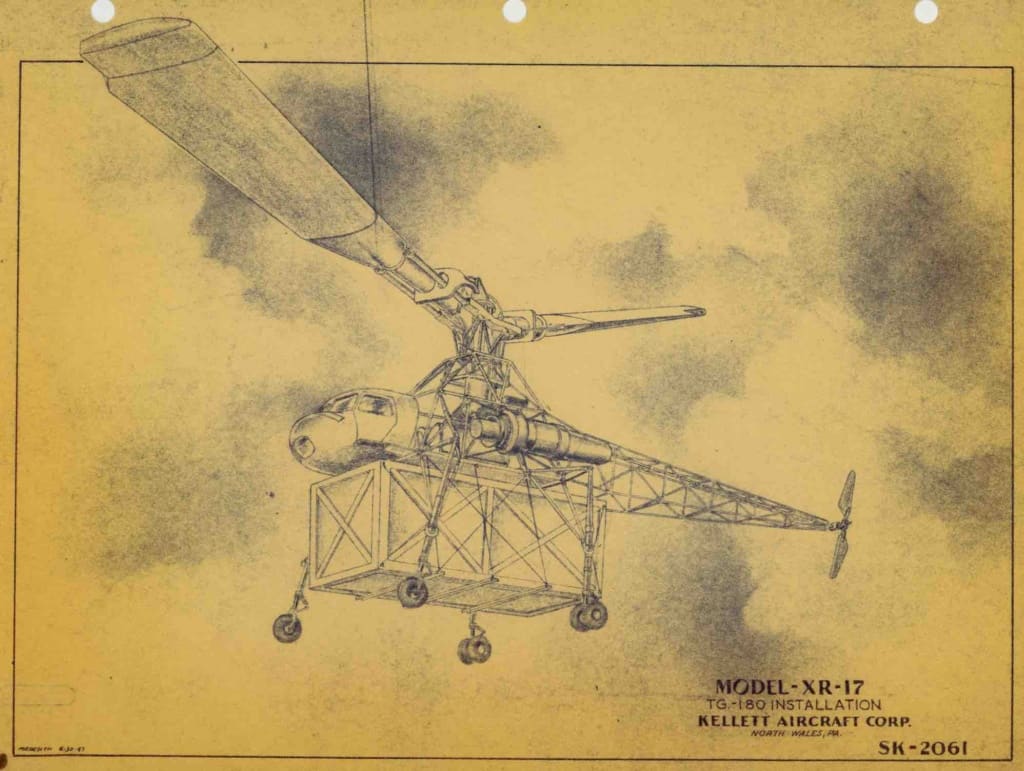

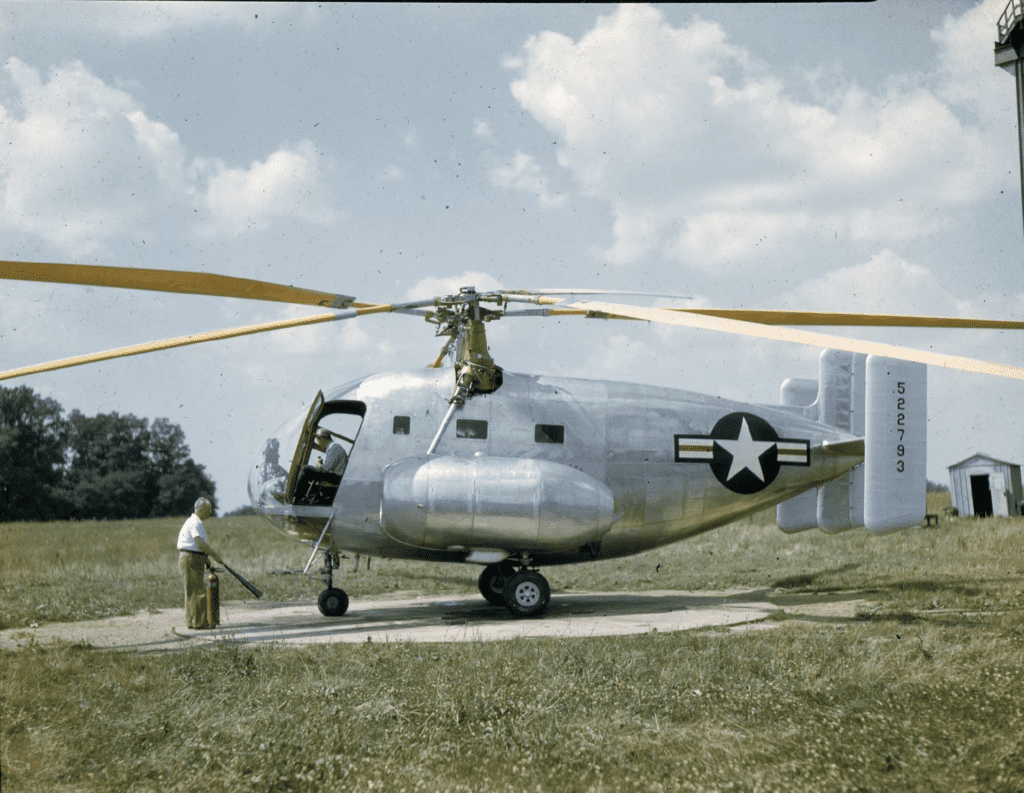

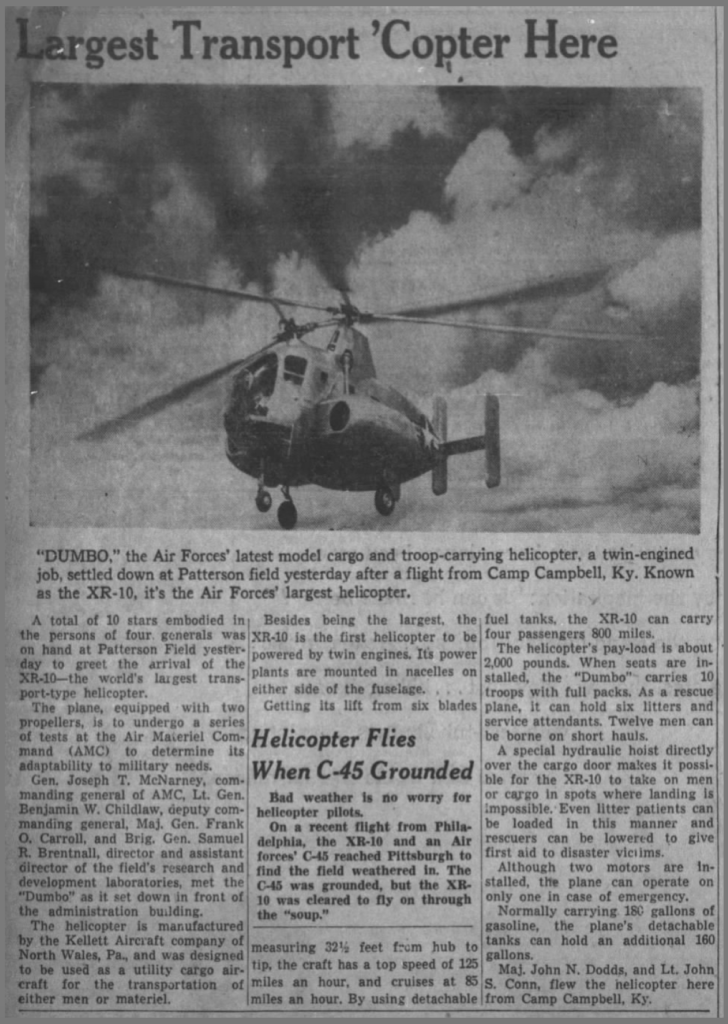

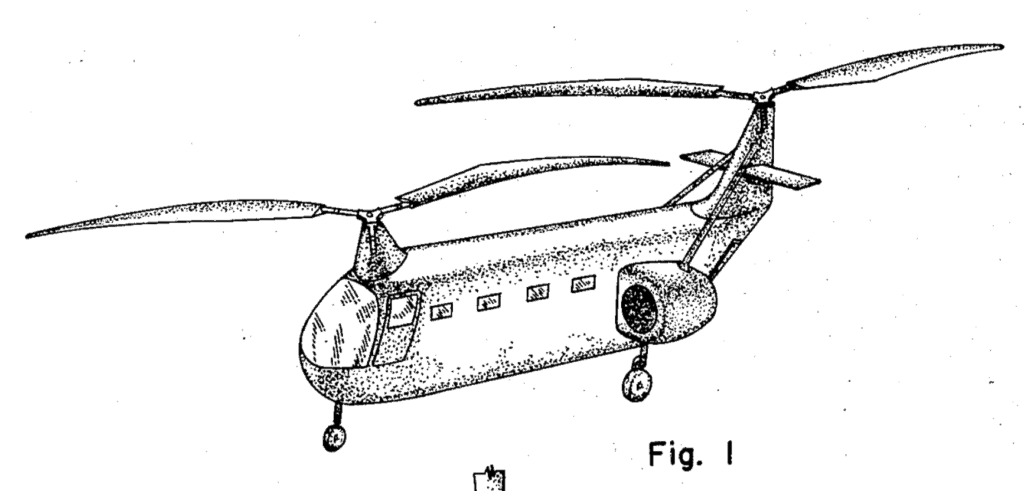

Constructed to meet an April 1944 Air Force request for proposals to build a “Utility Cargo Helicopter”, Kellett completed initial construction of the XR-10 in December of 1946. 97XH-10 Helicopter; Development of Kellett Model, C.W.Kuehne, USAF, Air Material Command. AF TECHNICAL REPORT # 6163, filed December 13, 1952, p iii The XR-10 helicopter featured two Continental engines mounted on side nacelles. 98After the war, Continental introduced its own R-975 version for aircraft, the R9-A. Though it was basically similar to other R-975 engines, and its compression ratio and supercharger gear ratio were … Continue reading Like the XR-8A, the XR-10’s engines powered two counter-rotating, intersecting rotor blades, each at an angle.

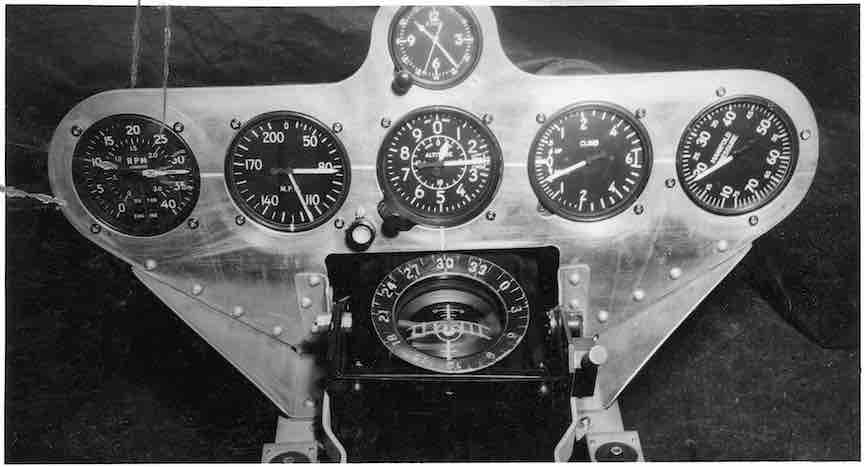

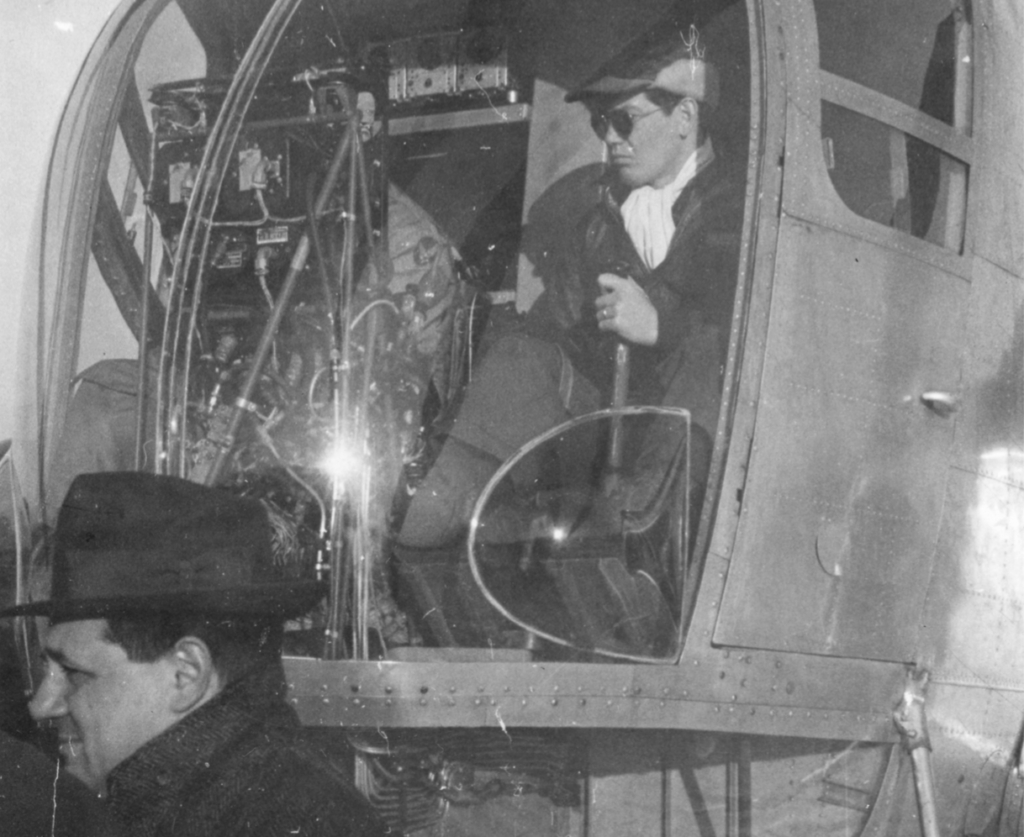

Bayer was hired to act as co-pilot beside Dave Driskill as the two men conducted ground and flight tests of the XR-10 beginning in December of that year. In 1947, Driskill and Bayer began testing the XR-10, tied to the ground with the engines gradually brought up to speed. Though they were born 26 years apart, day after day the two men sat side by side. Driskill seems to have given instruction to Bayer using a method common at the time–don’t say much, just watch and let your student sweat bullets. 99I had a flight instructor who flew during WW2. I am familiar with this method. From Driskill, Bayer learned intense attention and perseverance..There had been some discussion of a less flexible rotor design with the XR-8A was not adopted in the XR-10–creating a significant risk of rotor blade collision particularly when autorotating yet reducing the craft’s weight. 100THE XR-10 specs. R-10, H-10 1947 = USN. 10p R-8; two 425hp P&W R-985; rotor: 71’0″ length: 29’2″ v: 105/x/0 range: 350. Intermeshing rotors. POP: 2 as XR-10 [45-22793, … Continue reading

I SENT DAVE TO THE FARMHOUSE – the mentor and his protege.

As Driskill and Bayer prepared for and then began ground tests of the XR-10, an event illustrates the dynamics of their relationship. In this, though 26 years younger, Bayer would assert control. When pressed, he would act quickly and, with those who trusted him, take charge. Bayer wrote an account of the event in a letter to Rita.

Driving back to the plant over a lonely road I noticed a car that had gone off the road, hit a tree and knocked it over, went through a big heavy fence and turned over. I said to Dave, “That wasn’t there when I passed here on my way to pick you up.” I stopped the car and ran over. I looked inside and there was an old man pinned in the wreckage (and I do mean wreckage.) It was really a mess. He was soaked with blood, all cut up and had the windshield in his face and the steering wheel in his chest. I sent dave to the farmhouse nearby to call an ambulance and the state police. I didn’t want to move the man because I thought he might have a broken back or something. He was pretty well pinned in anyway and was unconscious. I reached in through the broken windshield and felt his pulse. He was still alive. Then I started pulling glass out of his face so he wouldn’t rub it into his eyes. He regained consciousness and started trying to move. I told him to be still so he wouldn’t hurt himself any more. Then I asked him if he could move his feet and hands. He could so I figured his back wasn’t broken so I straightened him up a little and reached in and wiped the blood off his face as best I could. He was hard to get to. He was still stunned and pinned in so I talked to him and told him to keep still and we would have him out as soon as the ambulance came. Then Dave came back, and shortly after that the ambulance arrived. We then helped the doctor and nurses get him out of the car and on the stretcher into the ambulance. Then we drove to the plant and resumed our work. 102LETTER AL TO RITA, Dec. 15, 1946.

LACK OF FLYWHEEL EFFECT – test thrills

During January of ’47, while driving back to Lansdale from Christmas in Schenectady, Bayer stopped to pilot the Sikorsky S-51 and the Brantley–the helicopters that had attended the GE Air Research Demonstration the previous spring. 103Bayer Logbook Jan 1 and Jan 2, 1947 These would be his first flights in a helicopter. Nothing in his logbooks suggests he had as yet had any formal instruction in helicopters. It can be inferred that having been checked out in the autogyro he now considered himself qualified to fly a helicopter. However, Driskill would soon give him formal instruction in piloting the XR-8A and sign off on that instruction in Bayer’s logbook.

Back at Kellett, ground testing of the XR-10 began. The soon engines and transmission developed problems that would require weeks to repair. 104LETTER JAN 7 1946 Bayer began to write his fiancé, Rita, almost daily, professing his love and reporting on progress.

“You asked about the transmission on the XR-10 being fixed. Yes, it’s all fixed. I guess I didn’t tell you what happened to the engines, Probably because I didn’t want you to worry about something that isn’t worth worrying about. Just after I got back, we ran the engines on the XR-10 again. First we were running the left one. All of a sudden we heard a very shrill screeching in the engine and an awful clatter. Dave and I pushed every button we could think of to shut it off quick. Next, we ran the right one. It ran for a while and suddenly something similar happened. Upon inspection, we found that the main accessory section gear and all the gears in its gear train on both engines flew apart. This was caused by torsional vibration in the crankshaft of the engine due to a lack of flywheel effect, and a few other things you wouldn’t understand. (It’s nothing to worry about just so long as it didn’t happen in the air.) To remedy this situation it is necessary to add additional flywheel to the engine which calls for a re-design of the transmission house etc.etc.etc. (You wouldn’t understand the rest, I don’t think) Anyway, the engines are out of the ship and we have two new engines to put in after the engineers figure out how to put bigger flywheels , etc.etc. It will probably take 2-3 weeks before we run the new engines. Dave has gone back to North Carolina, until we call him.” 105LETTER BY AL, Jan. 7 1946 The problem is referred to in XH-10 Helicopter- Development of Kellett Model, C.W.Kuehne, USAF, Air Material Command. AF TECHNICAL REPORT # 6163, filed December 13, 1952, p 2 Al concluded this letter with a page of song-titles that described his love. The Army gave permission for modification of the control systems. 106LETTER BY AL, Jan. 8, 1947

As described by Lambermont in 1958: The rotors were driven by two engines mounted on nacelles on either side of the fuselage so as to leave the cargo space unobstructed, and cooling was by the flow of air induced through the nacelles. Rotor head linkage allowed the blades to pivot in the horizontal and vertical planes. In the horizontal plane, blade movements were damped by vibration dampers; the position of the blades was a function of the centrifugal force and the loading conditions, but there were, of course, stops to limit these movements. The rotors were synchronized through a cross drive between the upper transmissions. 107P.Lambermont, “Helicopters and Autogyros of the World”, 1958. Quoted: https://sites.google.com/site/stingrayslistofrotorcraft/kellett-xr-10

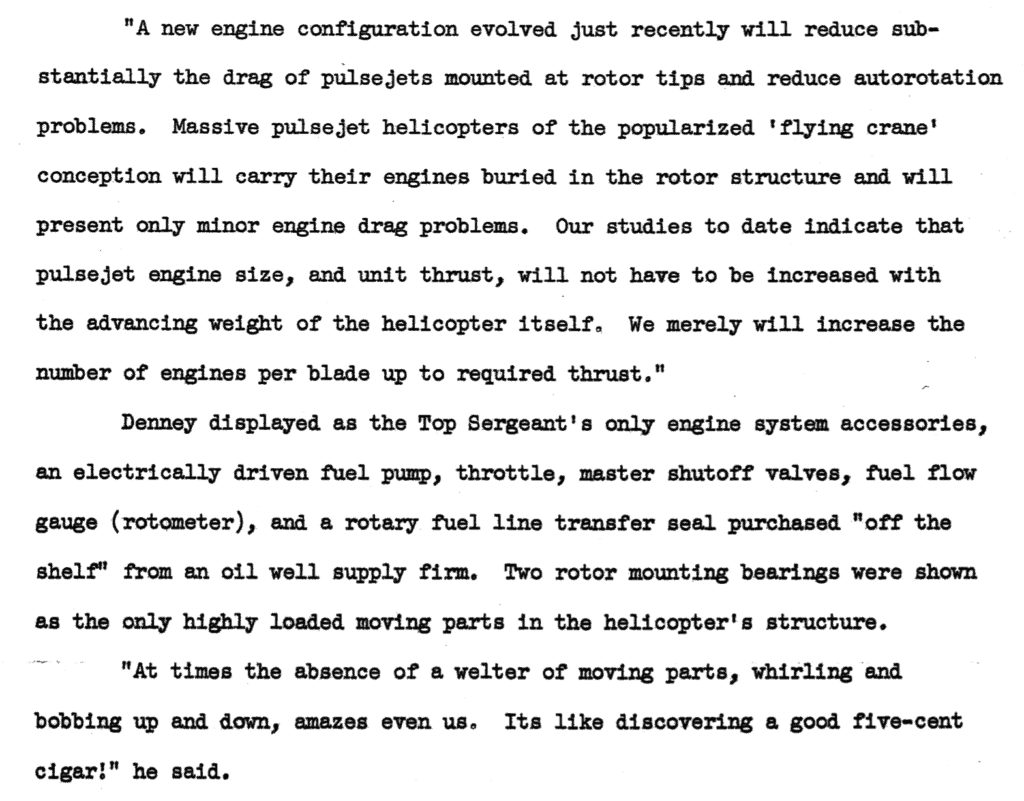

As the military considered the weight savings possible if a traditional engine could be eliminated from a helicopter and looked at captured German helicopters with their ram jets mounted at the rotor tips. Such a craft might be very efficient and, without the weight of heavy engines, lift great weight. The military had another captured German helicopter with cold-cycle powered rotor blades to study–the Doblhoff helicopter/autogyro with a rear propeller plus jets mounted in the blades for a jump start. During October of ’45, Major Wilson had asked Bensen to look at a DoblhoffWnf 342 V4 . 108GE Memos and Correspondence, Bensen, Memo. Oct. 22, 1945 The AAF shipped one by a Fairchild C-82 to Schenectady, New York on December 6, 1946. While the XR-10 repairs proceeded, Bayer returned to Schenectady to write a report on the Doblhoff. 109LETTER JAN 6 1946

Wilson noticed the high struts used on a lumber truck and this became the source for a craft built on four long landing gear that would envelope a cargo container. 110Stefano remarks, cited Porter p34 The call for bids specified a combination tip propulsion system like that on the Doblhoff. 111Porter p35.

At GE, Bensen continued to study the Doblhoff. He severely injured his spine in a crash of the Doblhoff . Bensen wrote a fuller report on the German machine during May of 1947.

Copies of Bayer’s report on the German Doblhoff helicopter went to Kellett Aircraft. And he sent a copy to Rita. In the report, he commented that it seemed, built more as a test rig than a flying machine. In January, though Kellett was already committed to the XR-10, the military asked Kellett Aircraft to build a “Flying Crane” with ramjets. They had already made hollow blades for Bensen’ Heliplane project–the fuel piped through them to the tips.

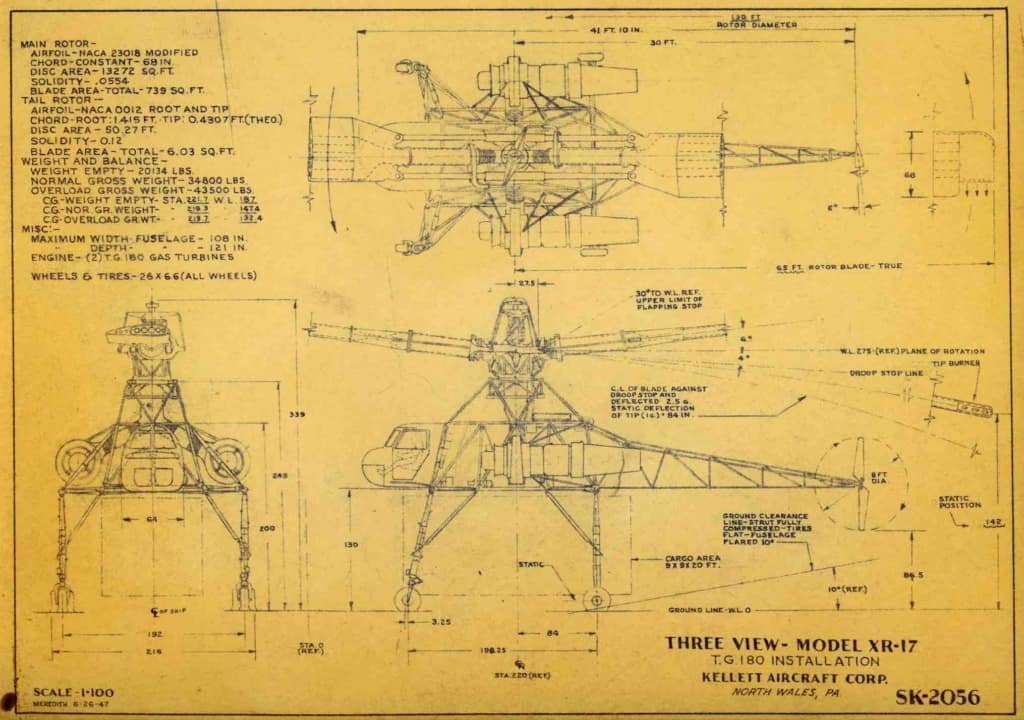

Repairs on the XR-10 continued into February. Bayer spent this time doing differential and integral calculus, preliminary performance calculations for the XR-17, jet helicopter–the Kellett “Flying Crane”. 113LETTER, AL TO RITA, Feb. 5, 1947 The giant cargo helicopter would be powered by air bled off from the compressor section of modified engines and ducted through hollow rotors to jets at their tips. The design eliminated complex transmissions and reduced weight. Also, as there was no transmission based torque tending to turn the craft in the opposite direction from the blades, the design eliminated the need for a tail rotor.

That February, Bayer’s doctor told him what other doctors had already said –that he had never had lymphosarcoma, that there had been a misdiagnosis. 114LETTER, AL TO RITA, Feb. 5, 1947 Bayer was not wholly reassured, he continued to worry about the diagnosis in letters to Rita.

“HOLLYWOOD” – style, flair, glamour

Bayer held Howard Hughes as his hero and, over the years, he often wore a suit and tie or, at least, a dress shirt, while test piloting. This might strike some as affectation. However, it proved central to his vision of himself and of the helicopter–adding glamour, dashing and romance to the world of the helicopter. As described more below, Bayer separated his sense of himself from Howard Hughes during the early 50s, yet he never ceased to embrace glamor and style as an intrinsic to himself and his work.

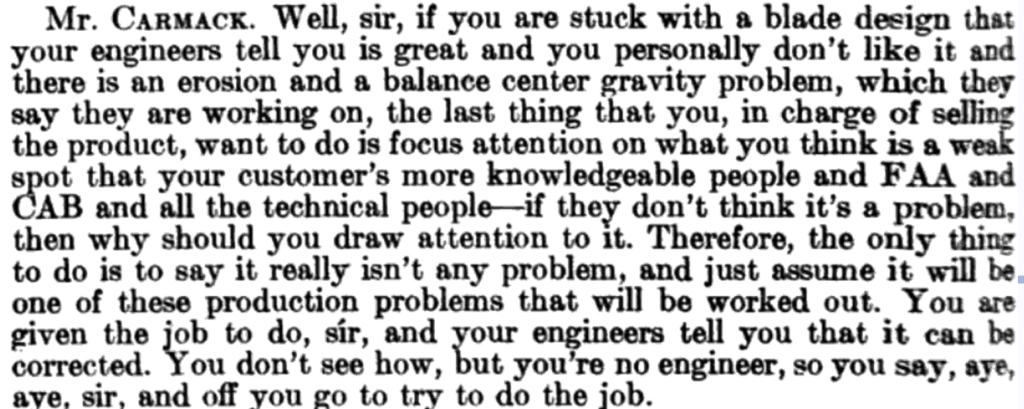

In Bayer’s story and the story of the mobile tactical helicopter, “cool” means not simply a look. Cool implies an approach to life–a daredevil competence. Cool means a dashing look that mirrored a dashing function. Ultimately, in the world of helicopters, cool meant a craft flitting about the sky, flown by a pilot who had mastered the three dimensions. This was not the XR-10. The XR-10 was not cool. Nor was the Flying Crane. Still in 1947 and ’48, these were Bayer’s assignment. His experience in these ponderous crafts allowed him to partner with, talk to and understand engineers whose creativity would ultimately define the technical elements of cool in a helicopter. They shared a desire for a revolution in the flying machine. Throughout his life, with his dress and good looks, Bayer charmed some people. Others were repelled. During the late 1940s, Emma and Clarence, Rita’s parents, didn’t like Bayer. During mid January, Rita wrote Bayer and told him: